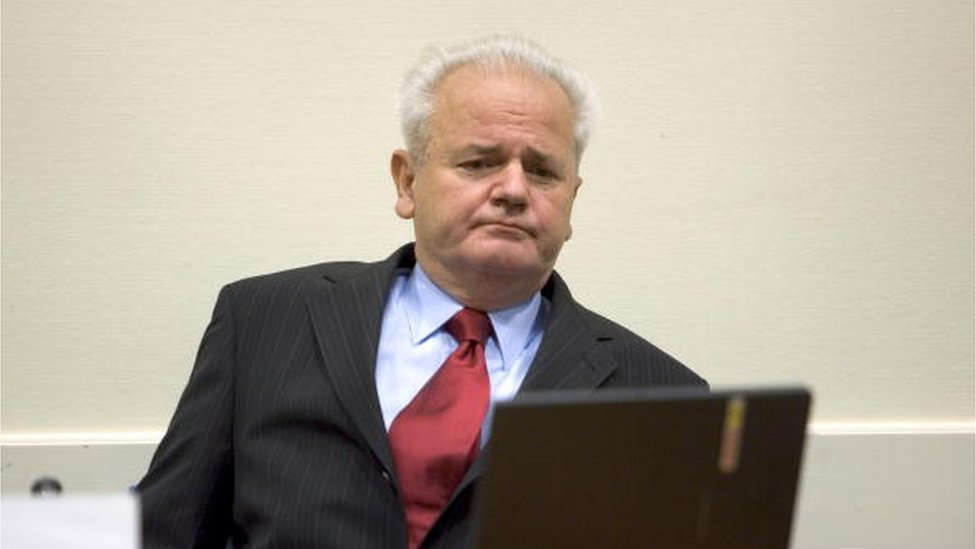

"Today, Mr. (Slobodan) Milošević is a man of outmoded political thought, devoid of the ability to strategically look at the challenges facing our country".

That Milo Đukanović is not this stated for the Serbian weekly Time in 1997 and thus said 'no' to the politics of Slobodan Milošević - the question is in which direction his political career would go.

This sentence, as well as the political break with Momir Bulatović, were crucial for Đukanović to be elected as the President of Montenegro for the first time exactly 23 years ago - on October 19, 1997, according to BBC interlocutors.

"Milo Đukanović was a shadow of Slobodan Milošević until that year in 1997, but even then he showed an incredible sense of political survival," the editor-in-chief of the Center for Investigative Journalism of Montenegro, Milka Tadić Mijović, told the BBC.

"He saw that Milosevic was nearing his end and took advantage of that."

Political and journalistic eyewitnesses of the event in 1997 describe for the BBC - whether the vote was "for Milo or for Momir or for Serbia or the West", how Djukanović managed to convince the party to completely change the policy in his favor in just two months, but also what his capacities are for "political survival" today.

- Milo Đukanović: "No one will bring me down"

- Dritan Abazović: "We overthrew the Balkan Lukashenko"

- Slobodan Milošević: The Mystery of the Brain

Although he changed positions, this anniversary finds Đukanović in the presidential chair again, but in changed political circumstances.

While waiting for the formation of the Government of Montenegro, the united coalition of the opposition won a total of 41 parliamentary mandates in the parliamentary elections, exactly as many as are needed to have a majority in the assembly.

Sessions until dawn and the breaking of epochs: Who (we) were for Yugoslavia

Momir Bulatović and Milo Đukanović managed Montenegro together with Svetozar Marović until 1997.

For an activist Džemal Perović, who was then active in the Liberal Union of Montenegro, the first signs of a split looked "rather strange".

"They started not long after Bulatović gave the mandate to form the government to Đukanović, with the words I'm paraphrasing: ... to that dear man... who is capable of making money out of nothing," Perović told the BBC.

"Then the slight taking of sides began. Some details of course became known to the general public much later. This is what Bulatović described in his book - as Đukanović's initial consent to be 'just a pebble in Slobodan Milošević's shoe'".

But in the spring, Đukanović gave an interview to Vreme where he made a departure from the politics of Slobodan Milošević, and Bulatović and some other members of the Democratic Party of Socialists publicly criticized him for that.

- Who are the people at the top of the current Montenegrin opposition?

- Whose monastery is Ostrog in Montenegro

- Is cohabitation waiting for Montenegro?

That's why he resigns from the party, but quickly returns - now at the suggestion of Bulatović.

Only a few months later, there is a final break between the political comrades at the meetings of the DPS main board.

Miodrag Vuković, the vice-president of the Government of Montenegro from 1996 to 1999, and still a close associate of Milo Đukanović, tells the BBC that "in those days, eras were breaking at the party meetings".

"Bulatović asked the members of the main committee of the party to adopt four conclusions, and one of them was - that Yugoslavia has no alternative," says Vuković.

"Milo Đukanović was against it, so that vote was actually a crucial stumbling block between the two".

Vuković says that he "always stood by Milo", but at the first session of the party he still voted against him.

"I and most of us in the DPS were too emotionally attached to Yugoslavia, and too little with reason," says Vuković.

"Djukanovic was then knocked out".

Of the 146 members of the main committee of the party, only seven of them supported Đukanović.

However, just two months later, in July 1997, Vuković changed his mind.

And he wasn't the only one.

- Why did Montenegro go out on the streets

"At the next session, Milo won the majority. Then I voted for him too," says Vuković.

“You're asking me what? Well, I had two months to realize that he was right. Some of us figured it out in a month or two, and some of us needed more."

"We were faced with the fact that Yugoslavia is facing abuses and turning against individuals, human interests, especially Montenegro and its people".

Milka Tadic Mijović was the editor of the only independent weekly in Montenegro - Monitor, and she worked as a correspondent for numerous foreign media.

He remembers, he says, those sessions of the party's main committee "which lasted until dawn" very well.

"When Đukanović refused to vote for the item on Yugoslavia at the first session - it was a shocking turn for everyone in Montenegro," says Tadić Mijović.

"Until then, Montenegrin politicians only nodded to Slobodan Milošević, and then they saw another option".

When asked how Đukanović managed to turn the party against him, the journalist says that he "thinks he used all legal and illegal means".

"For Milo or for Momir"

Vuković says that at those party committees they did not "vote for Mir or Momir, that is a simplified understanding".

"At that time, we voted for the policies they had - Bulatović was for a state with Serbia, Đukanović for an independent Montenegro," says Vuković.

As Bulatović did not accept the victory of Đukanović in the presidential elections, in 1998, Vuković says, Montenegro was on the verge of civil war.

"That January, Milo called me from America and asked about demonstrations, because Bulatović's supporters took to the streets," he says.

"I tell him - there is no turning back here. Somehow it calmed down after that."

On the other political stage, for Džemal Perović, the atmosphere of "are you for Milo or are you for Momir was false patriotism".

"In terms of keeping the levers of power, secret and public police, they were the same. It's like choosing between Tito and Stalin," Perović told the BBC.

"The impotence of those who advocated for the democratization of society, the dismantling of the inherited communist structures of government, a sort of fall of the Berlin Wall in Montenegro, was demonstrated in the elections, where Momo and Milo took about 90 percent of the votes."

However, in the presidential elections of 1997, the party he belonged to - the Liberal Alliance of Montenegro - supported Đukanović in the second round against Bulatović and helped Đukanović become the president of Montenegro for the first time.

"From today's position, I think it was a bad decision, even though it was inevitable at the time," says Perović.

"In the first round, Bulatović won with some 15.000 more votes.

"If Bulatović had won, Đukanović's wing would have had nowhere to go, it would have had to join the European path, which the Liberal Alliance was the first to trace in 1990, with some independent media and associations. Maybe then Montenegro would welcome October 5th more readily, with democratic capacities."

Why Đukanović turned around: the West and Milošević

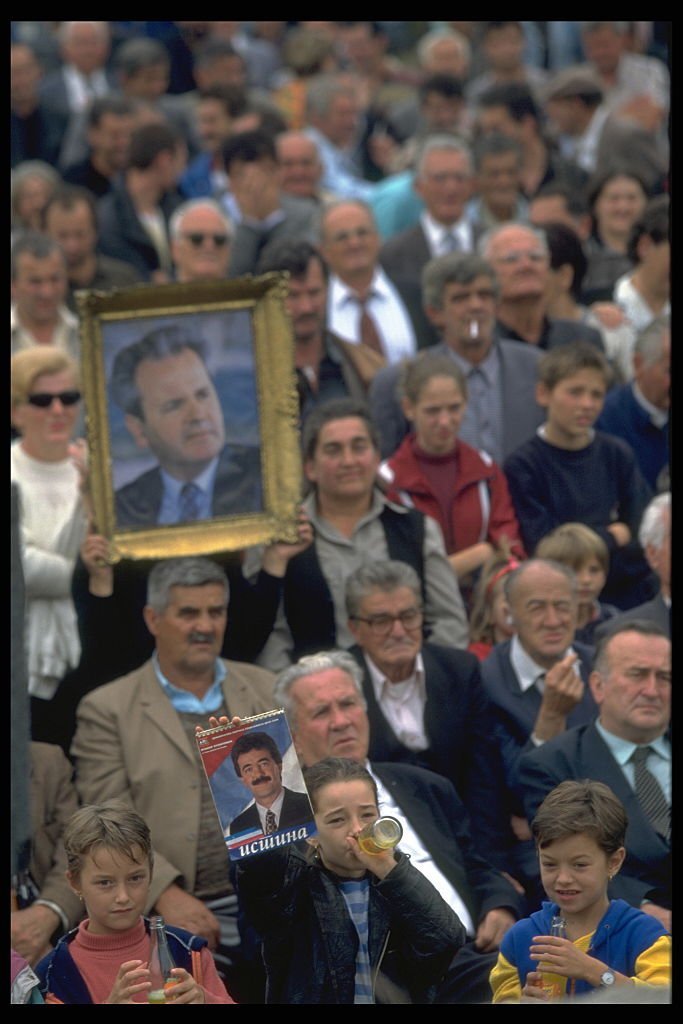

After the large demonstrations in Belgrade during 1996 and 1997, Tadić Mijović says that "everything indicated the beginning of the end of Slobodan Milošević".

"Within Montenegro itself, there was deep dissatisfaction due to sanctions and war, and there was also a desire for independence," she says.

"Djukanovic is a politician who always has his back.

"First it was Milošević, and then he turned to the Western allies and received their support for years, regardless of internal politics, which is the embodiment of a lack of democracy, deep high-level corruption and problems with the media".

- Who's who in the parliamentary elections in Montenegro

- In the photos: Litija in Montenegro

- Montenegro and NATO

Džemal Perović thinks that both Djukanović's departure from Milošević and his turn to the West "were false".

"This is precisely the catch - cooperation with the West has been established with an effort to maintain the status quo with Serbia. For the West, which already knew that it was dealing with a Balkan butcher, it was enough to say that Milosevic was a 'true politician,'" says Perović.

"It is important to note here that Đukanović, as the President of Montenegro, sat regularly in the Supreme Defense Council of the FR Yugoslavia and the Union of Serbia and Montenegro until the NATO intervention.

"He voted for the involvement of the army in Kosovo and the indiscriminate shelling of villages, which later led to NATO intervention".

Miodrag Vuković thinks that Đukanović's turnaround did not start a few months before the party sessions, but lasted since the creation of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, whose members were Serbia and Montenegro.

"There were always problems there. I also worked on the constitution of that new community, and the problems always came from Belgrade," says Vuković.

"The community was completely dysfunctional, and Montenegro had very little power there."

Vuković says that he remembers the Hague Conference on Yugoslavia in 1991, when Bulatović signed the peace plan.

"At that time, I was a member of the Montenegrin parliament. We had an extraordinary session until dawn where we discussed whether or not to sign Peter Carrington's plan for solving the Yugoslav crisis.

"Everyone balanced - both Bulatović and Đukanović and waited for Belgrade".

Peter Carrington's plan in The Hague, which included international recognition of the sovereignty of all Yugoslav republics, was signed by representatives of all republics - except Serbia. Momir Bulatović signed first, then asked to withdraw his signature.

"We were in the office of the President of the Assembly and listened to the conversation between Bulatović and Milošević. Milošević first said that Serbia will also accept the plan, so Montenegro can too.

"We just prepare everything, when they say again - stop, we need to talk to Milosevic again, he said that it is not accepted. And so on in a circle," claimed the then vice-president of Montenegro.

Đukanović today and the Government of Montenegro

The party created in 1991 by Milo Đukanović and Momir Bulatović in the last elections in Montenegro for deputies won 11 mandates less than the combined opposition coalition.

Although Đukanović still has two and a half years of his presidential mandate, if the former opposition forms the Government - parties that are on opposite political poles will have to cohabit.

However, if the united opposition loses only one mandate - it will not be able to form the Government.

"Regarding the new events (in the political life of Montenegro), I think that this is a kind of victory for the defeated, an attempt to re-escalate the conflict within the Montenegrin social being and the division between Montenegrins and Serbs", thinks Đukanović's comrade Vuković.

"We will not make a fairground out of the parliament and we will come to the sessions. We have to be honest that we lost, even though the structure of the winners does not guarantee me a longer term".

- They only know about Đukanović's Montenegro

According to Perović, the further course of the formation of the Government of Montenegro will depend "on the sincere intentions of the new government, but also on foreign factors, which will now have no excuse for not having anyone to cooperate with".

For journalist Milka Tadić Mijović, this is "the beginning of Đukanović's end, which began as soon as he won the presidential elections".

"That's when the Koverat affair was opened, which talked about endemic corruption, and Djukanović was at the center of it," she says.

The Envelope Affair has opened fugitive businessman from Montenegro Duško Knežević with a video recording of him giving an envelope with money to Slavoljub Stijepović, the former mayor of Podgorica and the current general secretary of the state president Milo Đukanović.

However, the journalist thinks that Đukanović's potential should not be underestimated.

"Like in 1997, when he won over one party member at a time, he did that very often in the last few years at the national level, but also at the local level in the cities," says Tadić Mijović.

"The question is whether this is a historical turning point for Montenegro or whether there is an option for Đukanović to play something again.

"It's hard for me to imagine that scenario."

Follow us on Facebook i Twitter. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

Bonus video: