In the city of monuments, there is no place for his.

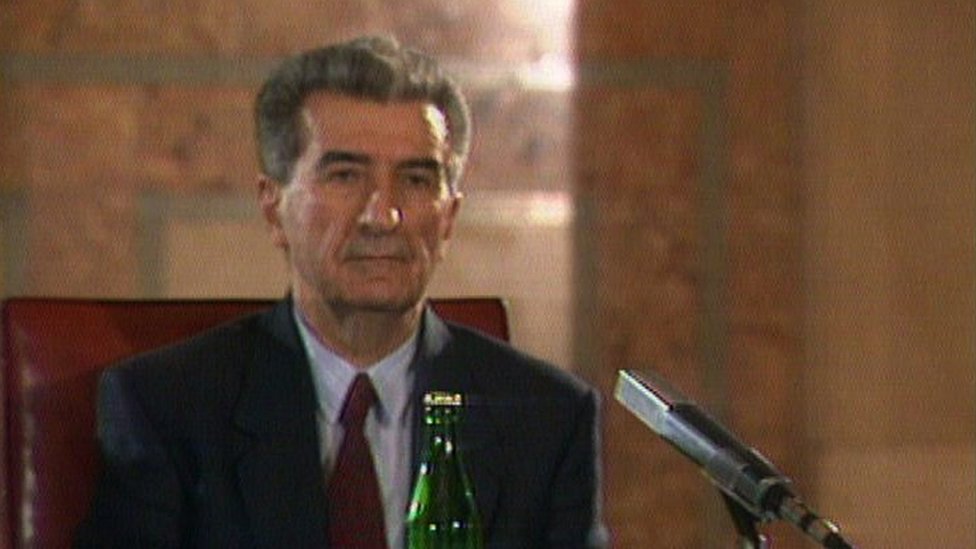

Kiro Gligorov was the first president of independent Macedonia, successfully leading it out of the Yugoslav federation in the early 90s, without war.

His career began five decades earlier, through activities in the Macedonian communist movement during the Second World War, and then through high political positions in communist Yugoslavia - Minister of Finance, President of the Assembly, member of the Presidency of the Communist League.

"Under his leadership, Macedonia managed to achieve what no other republic of Yugoslavia was able to achieve - to gain independence in a peaceful way, in the conditions of a terrible war.

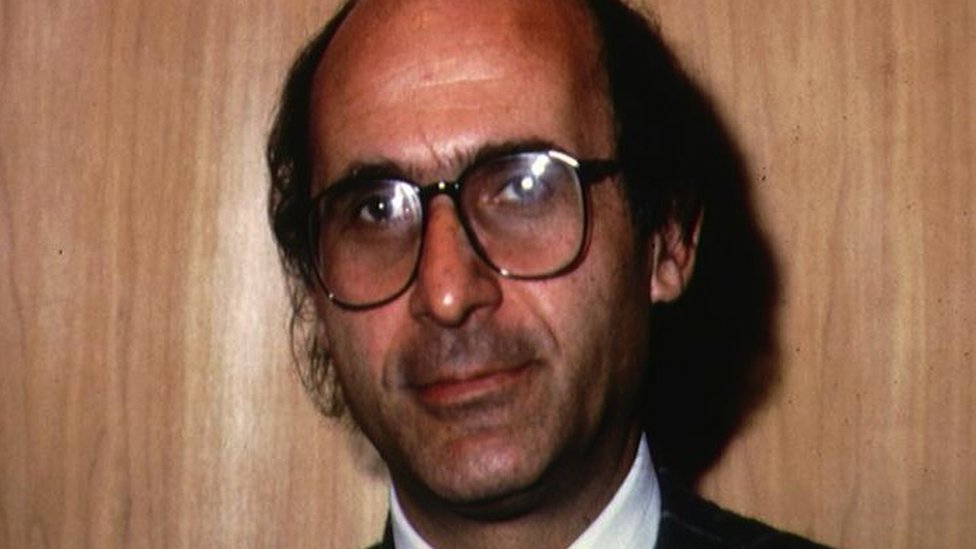

"His tact and intelligence brought the country and the people into the international community as a sovereign state, which came after numerous attempts to preserve the ties between the members of the federation," recalled the Macedonian head of diplomacy at the time, Denko Maleski.

- "The end of Yugoslavia was seen, there was no going back": Macedonia's independence - three decades later

- Vasil Tupurkovski: "The West allowed the war in Yugoslavia, now it does not allow it"

- Mesić told the BBC: "So much war has been fought and blood has been shed, and the borders have not changed even a millimeter."

Kiro Gligorov died in Skopje on January 1, 2012.

In the Macedonian capital, today one of the boulevards is named after him, as well as a recently opened modern school.

His statue is part of the monument to ASNOM (Anti-Fascist Assembly of the People's Liberation of Macedonia), the political body of Macedonian partisans at the end of World War II, in which Gligorov held one of the first positions.

However, there is no separate monument for Gligorov, although a large number of monuments have been erected in the city in the last decade.

From a reformer to a fireman in the time of socialism

Since the end of the Second World War, Kiro Gligorov in the communist movement has been given an important role that will describe a large part of his career - the guardian of Macedonian and then Yugoslav finances.

"Even though he was a lawyer by training, he was also a top economist," says his associate, diplomat Ljupco Arsovski.

He became the Minister of Finance in 1948 and remained in that position for four years, only to return to his post in 1962 as the Federal Secretary for Finance with the key task of reforming the economic system of communist Yugoslavia.

"Economic reform carried far-reaching ideas, it implied foreign policy changes, democratization, inclusion in the emerging new Europe.

"That was the time of his political ascension, which ended with the failure of that venture," Kira Gligorov's son, Vladimir, today himself a respected economist, told the BBC in Serbian.

After leaving the post of secretary for finance, he held mostly political positions, the highest of which was the presidential position in the SFRY Assembly.

He will swim in the economic waters once again, in the eighties of the 20th century, when he was invited to actively participate in the attempt to stabilize the Yugoslav economy in a country that was left without its lifelong leader Josip Broz Tito.

"The stabilization process led Malten from retirement, so he had a little less influence there, but until the breakup of Yugoslavia, he had the idea that things should be resolved as painlessly as possible.

"Nevertheless, that period of the XNUMXs was a period of aimlessness of a country, and someone who was outside the positions of power could not do much, except to introduce a little sense," concludes Vladimir Gligorov.

"Others rushed to war - we were not late"

The beginning of the nineties of the last century brought to Yugoslavia the first referendums for the independence of the republics - from Slovenia in December 1990, the beginning of armed conflicts in Croatia already in the spring of 1991.

At the other end of the SFRY, in Macedonia, Kiro Gligorov returned to active politics in 1990 through participation in forums where the future of the country was discussed.

In November 1990, Macedonians vote in the first multi-party elections, which do not bring a clear winner, but a political crisis and a deep social division that will follow the country for decades to come.

A technical government was formed, and Kiro Gligorov received the mandate of the first president of Macedonia in January 1991.

From that position, it will have a decisive influence on the referendum for independence that was held in September 1991, and especially on the referendum question that read "Are you in favor of a sovereign and independent state of Macedonia, with the right to join the alliance with the independent states of Yugoslavia?" ?"

More than 95 percent of the voters circled the affirmative answer and thus the conditions were created for Macedonia to stand in line for international recognition - albeit a little later than Slovenia and Croatia.

"There were many cries that we were late, that Gligorov was unable to free himself from his sentiments towards Yugoslavia.

"The truth was that others were in a hurry to go to war, not that we were late," the head of diplomacy at the time, Denko Maleski, is still convinced today.

He says that in that process Gligorov's ability to put out fires came to the fore.

"He also knew that he was hiding, but that was the result of a good assessment of the balance of power and who is leading the game in wartime, and that he depends very little on Macedonia."

"During the wars, he was one step behind events, while others were ahead - that's how he slowly led the country to independence."

- Milan Kučan for the BBC: "We didn't want to achieve the goal with weapons, but through conversation and agreement - but that didn't work."

- How the British lord's attempt to prevent war in Yugoslavia failed

- How Ante Marković, the last prime minister of SFR Yugoslavia, was overthrown

Political veteran Stojan Andov was at that time the president of Sobranja, the Macedonian assembly, and the leader of one of the leading parties.

He tells the BBC in Serbian that those turbulent times brought to the surface another quality of Kira Gligorov - indecision and waiting.

"There was a lot of hesitation, especially around the adoption of the constitution - when it was thick in that process, Gligorov often took refuge and went to Bosnia, to Alija Izetbegović.

"They were very good friends, together they proposed a platform for the reform of Yugoslavia."

Alija Izetbegović was the last president of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) as a member of the Yugoslav Federation and the first president of the Presidency of independent BiH.

While he was trying to consolidate institutions internally, on the Yugoslav ground, Gligorov was remembered as a co-author, along with Izetbegović, of one of the last offers to preserve Yugoslavia through loose ties between the independent republics.

The offer was flatly rejected by the other members of the federation, which had already moved far either on the path to independence or in an uncompromising desire to preserve a single, solid state.

"He was very dissatisfied with the fact that he participated in the breakup of Yugoslavia, he said that he was partly ashamed of having participated in it," says Kira's son Vladimir.

However, Gligorov's greatest success will be avoiding war - he personally negotiated the withdrawal of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) with the military leadership.

"He said - let the army leave here, it won't mean anything to us that soldiers die here, everything is ruined if one bullet hits a man."

"French President De Gaulle once said that all those who want to engage in politics, if they are under 50 years old, are still minors - years were Kira's experience," says diplomat Ljupco Arsovski.

The referendum decision, the departure of the Yugoslav army, international recognition and membership in the United Nations will enable September 8, the day of the referendum, to be celebrated as Independence Day in today's North Macedonia.

Hard inside, even harder outside

Although Macedonia managed to avoid war conflicts in the nineties of the 20th century, the situation in the country during that decade could hardly be described as peaceful.

The southern neighbor, Greece, strongly opposed the existence of the Macedonian state, claiming that it has a historical right to that name - the diplomatic dispute has hampered Skopje's economic and political ties for three decades.

"President Gligorov was aware of the great resistance among Macedonians who could not imagine someone taking their name.

"I also offered my resignation after the European declaration, which said that the country would be recognized if it did not have the word Macedonia in its name - I pressed for a compromise, so that we could move forward faster, and he was more careful," describes Kira's methods Gligorova's then head of diplomacy Denko Maleski.

Today's current dispute with the eastern neighbor over history and language was not a big problem then, but it could be foreseen.

"At that time, Bulgaria was a weak country, and it was practically just created by leaving a wider, eastern alliance.

"Macedonian independence was important to them then, they were the first to recognize it, considering that it was in their interest to finally break away from Serbia, and other issues were left for later," Maleski believes.

The internal lines of division were equally fierce - ethnic and political.

Relations between the Macedonian and Albanian communities became complicated already in 1992, when the ethnic Albanians in the west of the country proclaimed the Republic of Ilirid, which Skopje officially declared unconstitutional.

"Albanians from Illyria called Kira to talk, but he didn't want it - he thought it was too risky.

"He did not get involved in solving major issues in Macedonia, he distanced himself from the main problems," says the then president of the Assembly (Assembly) Stojan Andov.

- Zaev for the BBC: The referendum is a positive lesson for Europe as well

- Greece and Macedonia reached an agreement on the name

- North Macedonia: "At the moment, NATO is more important than negotiations with the EU"

On the other hand, diplomat Denko Maleski says that Gligorov's position has also brought positive things.

"The Albanians weren't too happy with him either, even though he did something that didn't work anywhere in Yugoslavia."

"He didn't even try to use national antagonism towards Albanians to strengthen his political position."

Because of his indecision, he was often criticized by the rival party of conservatives - VMRO-DPMNE, thus revealing another line of internal division, on the left and the right.

"Gligorov's internal issues were very complicated and difficult, he had to fight criticism from the opposition when solving the national issue with the Albanians, so maybe that's why he dealt more with foreign policy because corruption and crime started to develop in the country.

"He tried several times to solve things on the national level, but it was very unsuccessful - he was walking a tightrope, and it was difficult to be a magician," concludes diplomat Ljupco Arsovski.

All BBC interlocutors agree that Gligorov had no chance to reconcile the political differences between his compatriots.

"Our young democracy affirmed fierce behavior in rhetoric, attitude towards political opponents - everything was on the edge of a knife.

"Nationalists labeled him as a former communist, it was difficult to heal that gap among the Macedonians themselves," says Denko Maleski.

Assassination without a culprit as a culmination of pressure

When in October 1994 he defeated the candidate of the conservative VMRO-DPMNE in the first round of the presidential elections with more than 78 percent of the votes, Kiro Gligorov secured the presidential mandate until he was 82 years old.

Almost exactly one year later, on October 3, 1995, on the regular way from home to the cabinet, a powerful bomb exploded next to his car.

In the attempt to assassinate the Macedonian president, his official driver was killed, bystanders were injured, and Gligorov himself lost his right eye.

To this day, more than a quarter of a century later, the assassination attempt has not been solved - there were unofficial versions that found the culprits in almost all open internal and external issues in Macedonia, but no one was ever officially found guilty of the attempted murder.

A fragment of the mosaic of the diplomatic picture of autumn 1995 only hints at the complexity of the situation.

The day before the assassination, Gligorov returned to Skopje from Belgrade, where he had a meeting with the then president of Serbia, Slobodan Milosevic.

"He was very close to Milosevic until the assassination, until Holbrook came and Gligorov agreed to cooperate with him.

"With that, he resented Milosevic, and we spoke immediately after his return from Belgrade - he believed that he had sufficiently explained to Milosevic why he cooperated with Holbrook", the then Speaker of the Sobranja Stojan Andov outlines the Balkan relations after the arrival of the American envoy Richard Holbrook with the task of resolving the growing tensions in Kosovo.

Diplomat Ljupča Arsovski found out about the explosion in Athens, where he was working out the details of the diplomatic relaxation of relations with Greece, finally agreed upon in New York, a month earlier.

"I was supposed to be present at the meeting in Belgrade - to talk about borders, which was my responsibility at the time.

"Nevertheless, an extraordinary meeting with Greece was scheduled, so the news found me there."

In addition to the complicated relations with the northern and southern neighbors, the media wrote about the detained Bulgarian citizens, the repercussions that international relations have on internal ethnic and political conditions.

And it is precisely this segment of the unsolved assassination that Kira Gligorova's son points to.

"It cannot be interpreted differently than that the assassination was an internal matter.

"Macedonia is a democratic country today, but the assassination of my father shows that there are still forces that think that internal issues should be solved differently," concludes Vladimir Gligorov.

Sage or Balancer

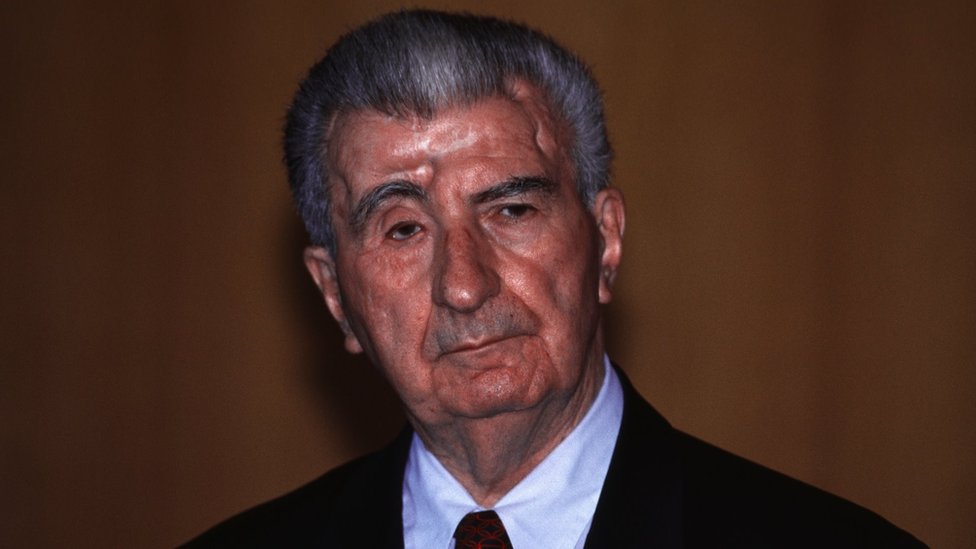

When his second presidential term ended in 1999, Kiro Gligorov retired once again - this time permanently.

He founded a foundation with his name and lived in Skopje until January 1, 2012.

He died in his home, after being discharged from treatment at the clinical center two days earlier, and was buried at the Butel cemetery in Skopje.

"Gligorov does not have the status of a national hero, and the big question was where to bury him, so in the end a solution was found that at least did not insult him," Stojan Andov testifies about political disputes.

His wife Nada died three years before him.

"My mother was very successful in her profession, my life was not connected to my father in any way, and the same was the case with my sisters - no one lived by their last name, we were a completely different world," says his son Vladimir today. .

In addition to the rich family, Kiro Gligorov also left a great social and political legacy.

"He had exceptional political and social abilities, patience, he is a rare man who survived everything that happened in Yugoslavia - the purges were inevitable, people changed.

"He possessed a strong inner psychological balance, with whomever he talked, he ended in a friendly tone," says Vladimir Gligorov.

In the description of his personality, two definitions will remain in conflict - a thoughtful or an indecisive man.

“He was balancing in the air, but there's a saying that if you're balancing a lot of balls in the air, you can't move forward fast enough.

"I was the one who wanted to move towards solutions faster because I was younger - but when an assassination happens, then it becomes easier to understand why things have to go that way," says former minister Denko Maleski and notes that Gligorov surrounded himself with associates who were younger than him and for whom it was the chance of a lifetime.

Diplomat Ljupco Arsovski believes that Gligorov made very smart decisions on the key issue, the preservation of the country and people.

"Even when things were relaxed, he still wanted time to pass, to think and only then make a decision, and that was just a matter of additional reflection, maturation.

"He was a sage who brought Macedonia a step forward."

Follow us on Facebook i Twitter. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

Bonus video: