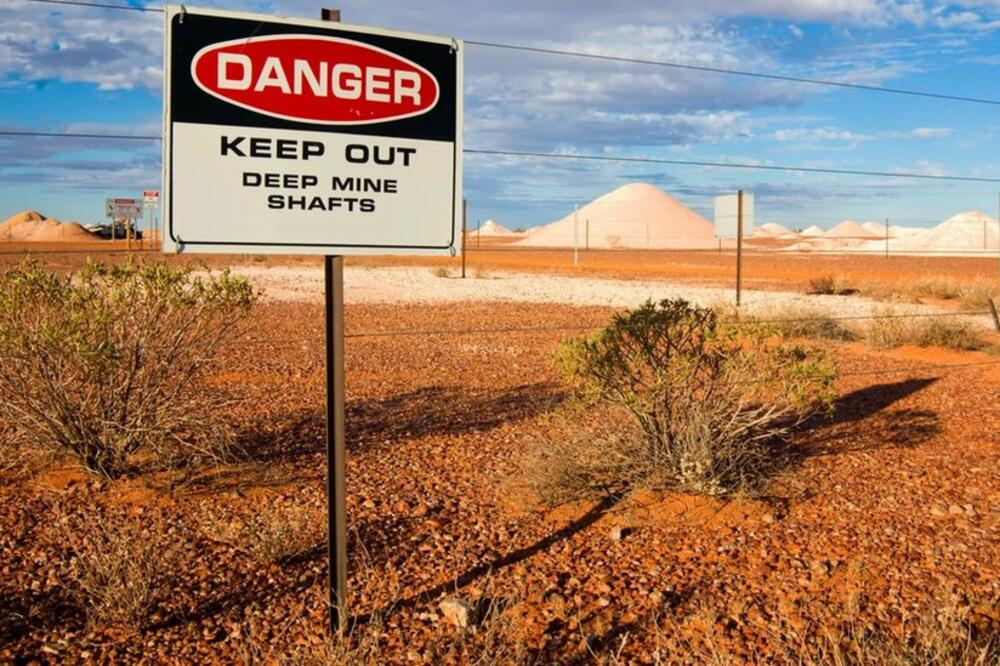

On the long drive into central Australia, as you travel 848 kilometers north of the coastal plains of Adelaide, there is a series of enigmatic sand pyramids.

Around them the landscape is completely barren - an endless expanse of salmon-pink dust, with a few determined bushes.

But as you go further down the highway, more and more of these mysterious structures appear - piles of pale earth, haphazardly scattered like long-forgotten monuments. From time to time, next to one, a white pipe sticks out of the ground.

These are the first signs of Kuber Pidi, an opal mining town with a population of around 2.500 people.

Many of its small peaks are the waste land of decades of mining, but they are also evidence of another local peculiarity - life underground.

In this corner of the world, 60 percent of the population lives in houses built in sandstone and iron-rich siltstone.

- A Turkish underground city where 20.000 people lived

- Windcatcher - ancient cooling technology

- How Ancient Atriums Keep Chinese Homes Cool

In some settlements, the only signs of habitation are vents that protrude and excess soil that has been dumped near the entrance.

In winter, this cave lifestyle can seem eccentric.

But during summer days, Coober Pedi - loosely translated from an indigenous Australian term meaning "white man in a hole" - needs no explanation: it regularly reaches 52 degrees Celsius, so hot that birds have been known to fall from the sky, and electronics have to be turned off. stored in refrigerators.

This year, the strategy seems more far-sighted than ever.

In July, the city of Chungking, in southwestern China, resorted to opening air raid shelters built during World War II in the midst of large-scale bombing from Japan to protect citizens from a very different threat: a ten-day streak of above 35 degrees Celsius.

Others have retreated to underground "cave hot" restaurants, which are popular in the city.

As a brutal three-month heatwave continues in the US with temperatures that even cacti can't stand, and wildfires burn parts of southern Europe, what can we learn from the people of Coober Pedy?

A long history

Coober Pedy is not the first or even the largest underground settlement in the world.

Humans have retreated underground to cope with challenging climates for thousands of years, from human ancestors lowering tools into a South African cave two million years ago, to Neanderthals creating inexplicable piles of stalagmites in a French cave during the Ice Age 176.000 years ago.

Even chimpanzees have been spotted cooling off in caves to help them cope with the extreme daytime heat in southeastern Senegal.

Take Cappadocia, an ancient district of central Turkey, for example.

The region is located on an arid plateau and is known for its striking, almost fantastical geology, with a landscape of sculpted peaks, chimneys and spiers of rock, like a fairy-tale kingdom.

But what is between them is truly spectacular.

According to popular rumours, it all started with the disappearance of chickens.

In 1963, a man was banging around in the basement of his home because his poultry kept disappearing.

He soon discovered that they were disappearing into a hole he had accidentally opened, and after clearing a way, he entered after them.

Things got even weirder from there.

The man discovered a secret passage - a steep underground path that led to a labyrinth of niches and further corridors. This was one of the many entrances to the lost city of Derinkuja.

Derinkuju is just one of hundreds of cave dwellings and several underground cities in the area, and is thought to have been built around the 8th century BC.

It was almost continuously inhabited for millennia - with its own ventilation shafts, wells, stables, churches, warehouses and a vast network of underground houses - and served as an emergency shelter for up to 20.000 people, in case of invasion.

As in Coober Pedy, underground life has helped the region's inhabitants cope with the continental climate, which fluctuates between hot, dry summers and cold, snowy winters - while outside it varies from well below zero to above 30 degrees Celsius, underground is always 13 degrees Celsius.

Even now, the region's man-made caves are known for their passive cooling capabilities—a construction technique that involves using design choices instead of energy to reduce heat gain and loss.

Today, the ancient galleries and passageways of Cappadocia are stacked with thousands of tons of potatoes, lemons, cabbage and other products that would otherwise have to be kept in the refrigerator.

They are in such demand that new ones are being built.

An efficient solution

Further along the road to Coober Pedi is the main town.

At first glance, it could be mistaken for an ordinary remote settlement - the streets are pink with dust, and there are restaurants, bars, supermarkets, gas stations.

On the ridge overlooking all this is the only tree in the city, a metal sculpture.

Kuber Pidi is eerily empty.

The buildings are widely spaced, and something is not right.

But underground, everything is explained.

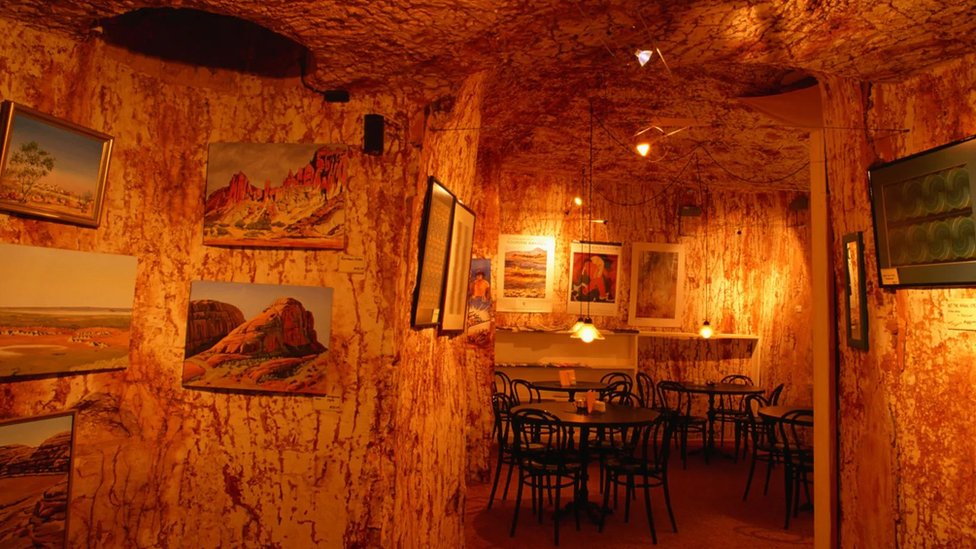

Some of Coober Pedy's 'dungeons', as they are called, are accessed through what look like small, ordinary buildings - as you step inside, their underground passageways gradually reveal themselves, like stepping through a wardrobe in Narnia.

Others are more obvious - at Riba's Camp (Riba's), where people can set up tents in alcoves several meters underground, the entrance is a dark tunnel.

In Coober Pedy, underground buildings must be at least four meters deep to prevent roofs from collapsing, and under this amount of rock, it's always a pleasant 23 degrees Celsius.

While above-ground residents have to endure hot summers and cold winter nights, where the temperature regularly drops to two or three degrees Celsius, underground houses remain at perfect room temperature, 24 hours a day, all year round.

Besides comfort, one big advantage of living underground is money. Kuber Pedi generates its own electricity - 70 percent of which is powered by wind and solar power - but air conditioning is often prohibitively expensive.

"To live above ground, you pay an absolute fortune for heating and cooling, when the temperature is often above 50 degrees Celsius in the summer," says Jason Wright, a resident who runs Riba's underground camp.

On the other hand, many underground houses in Coober Pedy are relatively affordable.

During a recent auction, the average three-bedroom house sold for around €24.000.

Although many of these properties were extremely basic or in need of renovation, there is a large gap between these valuations and those in the nearest major city, Adelaide, where the average house price is around €415.000.

Other benefits include zero insects — "when you get to the door, flies are jumping off your back, they don't want to go into the dark and cold," Wright says — as well as a lack of noise and light pollution.

- Has climate change already brought us deadly heat?

- More than three billion people will live in extremely hot places by 2070

The ideal setting

The question is, could underground houses help people cope with the effects of climate change elsewhere? And why aren't they more common?

There are several reasons why making dugouts in Coober Pedy is uniquely practical.

The first is stone. "It's very soft, you can scratch it with a pocket knife or your fingernail," says Barry Lewis, who works at the tourist information centre.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, Coober Piddy residents expanded their homes the same way they created opal mines - using explosives, picks and shovels.

Some didn't require much digging at all, and many locals used abandoned mine shafts as a starting point.

Today, they are often excavated using industrial tunneling equipment.

"A good tunnel boring machine can make about six cubic meters of rock an hour, so you could build a dugout in less than a month," says Wright.

However, manual digging is still possible, so when residents need more space, they sometimes just start digging.

And as an opal mining area, it's not uncommon for a renovation project to actually make money.

One man discovered a large gem sticking out of a wall when he was installing a shower, and a local hotel discovered opals worth nearly €985.000 while building an extension.

Moreover, sandstone is structurally sound without supports, so it is possible to make (literally) cave rooms with high ceilings, in any shape you want, without additional materials. In fact, tunneling in Coober Pedy is so easy, many locals live in elaborate, luxury apartments, with underground pools, games rooms, spacious bathrooms and high-spec living rooms.

One resident previously described the underground home as "like a castle", with 50.000 bricks and arched doors in every room.

"We've got some amazing dugouts here," says Wright, who explains that the tenants are known for their privacy—another possibility when you live underground—so you tend to only find out about them when you're invited over for dinner.

The question of moisture

However, the feats at Coober Pedy would not be possible everywhere. One of the main challenges with an underground structure is moisture.

Of the many stone dwellings inhabited by humans, most are found in dry areas—from the towers and walls built into the cliffs of Colorado's Mesa Verde, inhabited for more than 700 years by the ancient Pueblo people, to the elaborate temples, tombs, and palaces carved into the pink sandstone in Petra, Jordan.

Today, one of the last inhabited rock-hewn villages in the world is Kandovan, at the foot of the Sahand Mountains in Iran - a valley dotted with strange, spiky caves that have been hollowed out into houses, like a colony of termite mounds.

The area receives only 11 millimeters of rainfall each month on average throughout the summer.

On the other hand, underground construction in wetter areas is extremely inconvenient.

To waterproof the original London Underground tunnels, which were built in the 19th century, each was lined with several layers of brick and a generous coating of bitumen (more modern methods are used today).

But even with those precautions, there are still regular reports of black mold. The same problem plagues basements, bunkers and parking lots in high-rainfall areas around the world.

There are two main reasons for this: lack of ventilation, which can allow moisture from cooking, showering and breathing to condense on the cold walls of the cave, and groundwater - if the underground houses are built close to the water level.

Take the Hazan Caves in Israel, an elaborate network of underground hiding places built by Jews escaping persecution by the Romans in the 2nd century AD - complete with olive presses, kitchens, corridors, water tanks and a columbarium for holding burial urns.

There are not only houses underground in Coober Pedy - there are underground restaurants, shops, motels and even a Serbian Orthodox Church.

At only 66 meters in the cave, the temperature drops significantly compared to outside, but the humidity also jumps from just 40 percent to double the level.

This may be partly because the cave system is embedded in porous rock in a lowland area - where there is usually more groundwater.

With narrow passages and limited inlets, it also has poor airflow.

Carbon number

The travel emissions required to publish this story were 0 kilograms of CO2.

Digital emissions from this story are estimated at 1,2 grams to 3,6 grams of CO2 per page view.

But at Coober Pedy, which sits on 50 meters of porous sandstone, conditions are arid even underground.

"It's very, very dry here," Wright says.

Vents are added to ensure an adequate supply of oxygen and allow moisture from indoor activities to escape, although these are often just simple pipes protruding through the ceiling.

There are some other disadvantages of these heat wave resistant bunkers.

Lewis is currently living above ground in a trailer park, after his underground home - on the same site - collapsed.

"That doesn't happen very often," he says.

"She was on bad ground."

It is also not uncommon for residents to accidentally break into a neighbor's house.

Despite the obstacles, Lewis misses life in the dugout - and Wright would highly recommend him to anyone currently suffering from unreasonably high temperatures.

"There's no need to expose yourself to that kind of heat," he says.

Perhaps soon the unusual sand pyramids of Coober Pidy will begin to appear in other places.

Follow us on Facebook,Twitter i Viber. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

Bonus video: