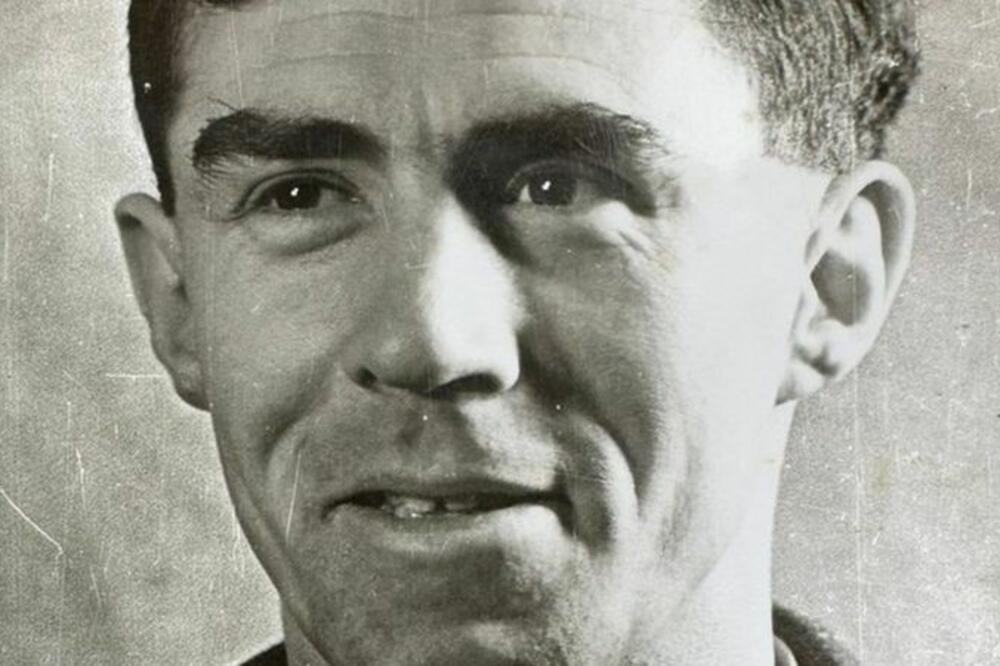

Squadron Leader Frank Griffiths escaped eighty years ago from Italian-occupied France during World War II.

He was the only surviving member of the aircrew whose RAF bomber was shot down in August 1943.

His escape culminated in a three-month journey in which he scaled some of Europe's highest peaks, walking 128 kilometers in three nights.

Now his great-grandson, Adam Hart, is retracing his safe and epic journey on foot.

- The story of a German woman from Vojvodina who survived the Ustasha camps

- The rebellious British soldier who drove German General Rommel crazy

- The tragic fate of Marcel - a small fighter against the Nazis

Hart set out with his uncle to visit the places and "beautiful families" that his great-grandfather had also encountered.

But even as a top athlete, Hart said the physical challenge made him respect his ancestor even more.

"I've done Ironman competitions, but I was in no way prepared for the grueling effort that required ups and downs," said the 22-year-old from Narberth, in Pembrokeshire, a county in south-west Wales.

"And we didn't even look out for the Nazis as we went!"

"We tried to follow his route faithfully and I'm very pleased with that, it gave us an understanding of what he had to go through much more than any photographs or a car trip could," Hart said.

Griffiths was part of No. 138 Squadron RAF, whose Halifax aircraft were adapted to carry cargo and men behind enemy lines.

They were supposed to deliver supplies to French resistance fighters, when a lucky shot from an Italian soldier's rifle pierced their fuel tank above the town of Mete (Meythet).

Griffiths survived only because he was ejected from the cockpit, his fall stopped by telegraph wires.

With a broken arm, facial injuries and a severe concussion, he was barely conscious enough to crawl away from the fire when the plane exploded.

But in a miraculous stroke of luck, the inferno distracted the Italian troops enough to allow a 14-year-old Frenchman to take Frank on a bicycle.

A French resistance group smuggled him into Switzerland and treated him for his injuries.

By October 1943 he had recovered enough to try to escape back to Britain.

But the winds of fate changed direction again.

"Since Frank had not officially entered the country, the Swiss authorities offered him the option of being interned by the Red Cross, or they would turn a blind eye and let him risk re-entering occupied France.

"Frank felt it was his duty to try to get home to rejoin the war effort," Hart said.

He also said that his great-grandfather had planned to board a train to northern France and fly out in an RAF Lysander, but as he was returning to Anmas near Lyon, the Gestapo swooped in and the resistance group that rescued him disappeared.

"Everything went wrong, he was wandering in the dark after curfew. He was forced to swallow a piece of paper with coded instructions when another resistance group dragged him into the house.

"Even if the Gestapo couldn't spot the lost British airman, they certainly could," he recounts.

Walking by night and sleeping in the barns of sympathetic farmers during the day, this group initially took him by a circuitous route through Toulouse and Perpignan, then took him with two American airmen over the Eastern Pass of the Pyrenees.

- "Father wrote to us every day while he was waiting to be sent to Auschwitz"

- Centenarian sentenced to five years in prison for Nazi crimes

- Bruce Old - tennis pioneer who interrogated Nazi scientists

'Always a proud Welshman'

For general security, no names are ever asked or given.

However, Griffiths once broke that rule on a trip, giving the young son of a resistance fighter his own French-English dictionary, writing on the cover: "The Englishman Griffiths."

"I don't know why he did it in the first place given the danger, but I especially don't know why he wrote 'English', Frank was always a proud Welshman," Hart said.

He said he was glad the risk was taken, as the Sack family eventually managed to reach Griffiths through the RAF in 1973, and he had the opportunity to visit them.

"Fifty years later, and 80 years after Frank first met the Sack family, we met them too."

Hart was introduced to a woman born in 1943, who is the same age as Griffiths' daughter.

She was six weeks old when he last saw her.

"I have two photos side by side of Frank holding both babies," he said.

"When the Saks showed me Frank's dictionary, at first I couldn't understand why they were laughing. Then they explained to me that the teenager Frank gave it to had flipped through the pages and underlined all the obscene words."

"It was touching to see that it was still one of their most treasured possessions."

The boy's granddaughter organized a lunch and invited friends and family, and then the couple were shown all the places where Griffiths had been hidden.

"It was a really emotional day," Hart said.

After saying goodbye to the Sacs in Spain, Griffiths was briefly arrested by the Spanish before being allowed to walk to Gibraltar, where he caught his flight home.

He was later withdrawn from frontline duty, but remained a test pilot in the RAF until the 1970s.

He died in Rutin in 1996 at the age of 84.

Watch the story of Eva Kor, a woman who survived the Holocaust and forgave the Nazis

Follow us on Facebook,Twitter i Viber. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

Bonus video: