Da years start in January everyone learns as children, but in Montenegro it means much more than just looking at the calendar.

That was the slogan of the Union of Communists of Montenegro before the first multi-party elections in 1990, which will significantly determine the fate of one of the six republics of the then Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRJ).

The elections followed stormy street protests in January 1989, when "young lions, beautiful and smart", as the media described them, 35 years ago, replaced the old communist leadership of Montenegro as part of an internal party conflict.

"The actors from the first plan of the protest, connected through the university, were mostly there for a very clear motive: that the system has been overcome and that it requires a crucial change in the direction of democratization," Milica Pejanović Đurišić, one of the leaders of the protest at the time, told the BBC.

The so-called anti-bureaucratic revolution gave birth to a new party and soon state leadership, which was taken over by Momir Bulatović, Milo Đukanović and Svetozar Marović.

The catchphrase was also created: "Nobody can touch Sveta, Milo and Momira".

And it hasn't, for decades.

- How the autonomy of Vojvodina before the breakup of Yugoslavia was drowned in yogurt

- Why the census in Montenegro causes tension

- After dinner and music, a serious conversation: Will relations between Serbia and Montenegro move in a better direction

- Filip Vujanović: "I am worried and scared about what will happen to Montenegro"

How protests led to protests

At the end of the eighties of the 20th century, the already complex situation in Yugoslavia became more and more complicated, while Croatia and Slovenia were increasingly preparing for independence.

After the death of Josip Broz Tito, the leadership of the country was taken over by the collective Presidency of the SFRY, which consisted of representatives of six republics and two provinces on the territory of Serbia, Kosovo and Vojvodina.

The main stage is being approached by a generation of young communist leaders who are looking for space at the top in all republics.

Official Belgrade's problem was how to secure the support of Kosovo and Vojvodina, as two additional votes in the Presidency, Živan Marelj, the former president of the Assembly of AP Vojvodina, told the BBC in Serbian.

In the numbers game, the fourth vote on Serbia's side could have been Montenegro, which would mean an equal relationship in the Presidency, so that no decision could be made without Belgrade's consent.

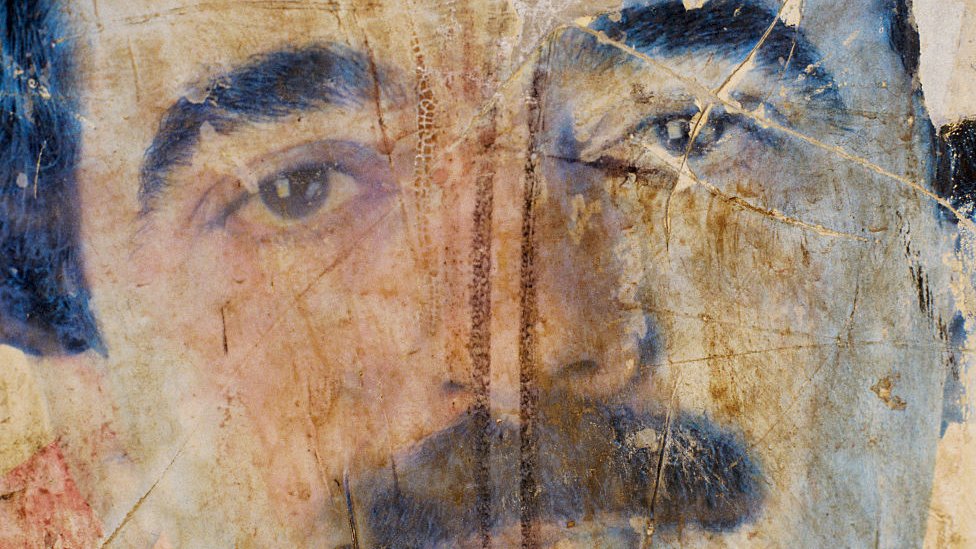

Poster by Momir Bulatović

At the end of the 1980s, Serbia was also colored by protests, from the north to the south.

In Vojvodina, in Yogurt revolution and in street protests, changes the previous leadership, with accusations that they deviated from the party path, and supporters of Yugoslavia come to their place, in which Serbia would have a leading role.

The streets of Kosovo are filled with Albanians who demand the status of a republic, but also with Serbs who oppose it.

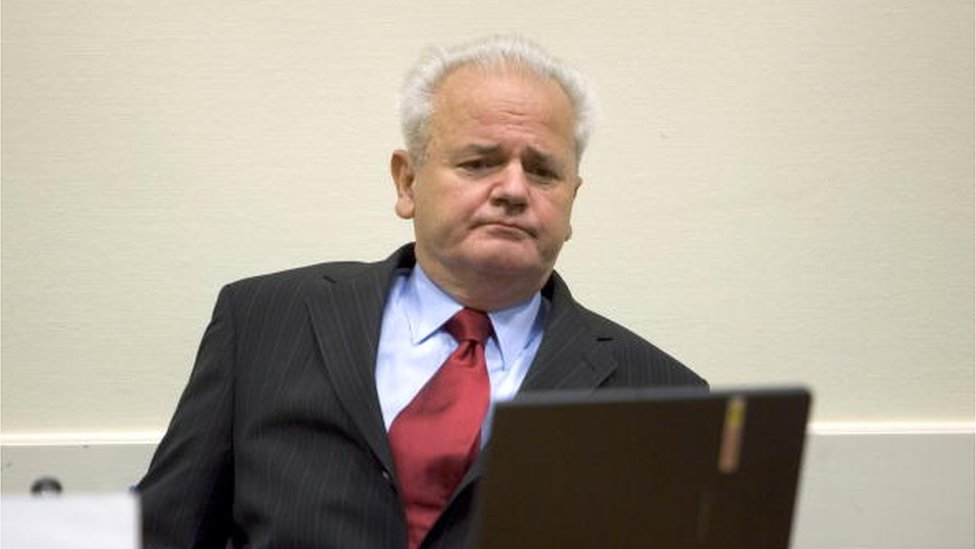

In such an atmosphere began the political rise of Slobodan Milošević, soon the president of Serbia, then Yugoslavia, and one of the key politicians for the unfolding of the Balkan crisis in the nineties.

- The rise of Milo Đukanović - from breaking up with Milošević to the longest-serving leader of Montenegro

- Memorandum to SANU: "Dynamite under the foundations of Yugoslavia" or an attempt to "preserve" the federation

- Do the demonstrations in Kosovo in 1981 still have consequences today?

- "The year when hatred deepened": Referendum in Kosovo - 30 years later

Montenegro welcomes that era with old communist cadres.

The President of the Presidency was Božina Ivanović, a member of the Communist Party of Montenegro since 1949, while the Montenegrin member of the Presidency of the SFRY was Veselin Đuranović, the former Prime Minister of Yugoslavia and its long-time official.

But the communist youths of the time, like Bulatović and Đukanović, who already became part of the only party during their studies, began to attract more and more attention.

Đukanović says that in 1989, he looked with sympathy at attempts to introduce some novelty into the ossified system at the time.

"At that moment, Milošević appears, who differs from others in the political life of Yugoslavia, if for nothing else, than for his completely new rhetoric, and he promises long-awaited reforms.

"It is something that captured the sympathy of a large number of people at the time," he stated in 1999 for RSE.

As he says, he did not assume that "manipulation of the people could take on such proportions".

The situation in Montenegro at that time was particularly "ripe for a great outpouring of discontent", writes Nebojša Vladisavljević, a professor at the Belgrade Faculty of Political Sciences, in the book "Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution".

The ground for the protests was already being prepared since the summer of 1988, when a meeting of solidarity with Kosovo Serbs and Montenegrins was held in the center of what was then Titograd.

The rally was preceded by longer activities of Serbian nationalists on the soil of Montenegro, he was talking Vladimir Keković, former head of the State Security Service of Montenegro.

"They established strong ties with persons who acted from the position of Serbian nationalism in Montenegro, especially in larger collectives," he said, citing companies Radoje Dakić in Podgorica, Železar and Pivar in Nikšić and the Podgorica Aluminum Plant.

The long economic crisis destabilized the entire Yugoslav economy, and in Montenegro "it was approaching collapse", Vladisavljević describes in the book.

Act One: October 1988

Beginning of October 1988, workers Radoje Dakić, the largest Titograd company, were welcomed on the streets.

They demanded double wages and fines for those responsible for factory mismanagement, subsidies for the company and tax cuts.

"Within two hours, we got people up, the strike started, we broke down the main gate and came before the assembly of Montenegro," says Pavle Milić, then leader of the workers from Radoje Dakić, for the BBC in Serbian.

The authorities offered the strikers a 30 percent higher salary, which the workers refused and headed towards the city center to meet the students, carrying the Yugoslav flag and Tito's picture.

"Fiery speeches were given in front of the assembly, people addressed the people," says Milić.

The officials promised them that the state and party authorities would urgently attend to their demands, but they demanded that the protest end.

The demonstrators replied that until their demands were met, they would remain in the town square, where more and more people joined them over time.

Vladisavljević writes that there were about 25.000 of them in the evening classes, judging that the number is huge, bearing in mind that Montenegro has a population of slightly more than 600.000.

Groups of demonstrators remained in the square overnight, until the then leadership of Montenegro made a decision to break up the protests and declare a state of emergency.

"They struck from Njegoševa Street in the middle, separated the people who came and beat the people," recalls Milan Vukčević from Radoje Dakić that day, in an interview with the BBC in Serbian.

When asked if he was scared, he answered briefly: "And who wouldn't?"

Clashes also took place on the road between Nikšić and Titograd, where the police intercepted Železara workers.

Tear gas was fired, several people were injured, and the demonstrators were forced to return to the city, just like those from Cetinje, who also headed for Titograd.

"The dispersal of the October demonstrations by force turned even those who were indifferent to the protests against the leadership," writes Vladisavljević.

"In some parts of Montenegro with an uprising tradition, the use of force against ordinary people was perceived as a sign of the moral decline of officials and deep disrespect of citizens."

High state officials of Montenegro then declared that they were defending political institutions and legally elected officials, pointing out the dangers of "Greater Serbian nationalism" and accusing The state security service for organizing "people's events".

Božina Ivanović, then president of the Presidency of Montenegro, called some protesters "emissaries who speak on behalf of other communities", and that it is a "well-organized network that has political demands."

"We are legal bodies in a legal country and a legal republic," he was emphatic.

Veselin Đuranović, a member of the Presidency of the SFRY from Montenegro, warned that the events in Titograd did not "happen spontaneously, but that behind everything is a well thought-out organization".

Pavle Milić, one of the leaders of the protest, does not hesitate to say that he previously went to rallies in Serbia with Kosovo Serbs.

As one of the reasons why he took the workers to the streets, he points out that "Montenegro has always been a country of freedom, sister and brother of the entire Serbian people".

"They, as leaders of Montenegro, did not pay attention to Kosovo, and there is the heart of every Serb... Kosovo is the heart of both Serbia and Montenegro."

When it boils beneath the surface

At least for a short time, political conflicts moved from the streets to the institutions, where big cracks were discovered in the previously unified communist party - some sided with the protesters, others sided with the government.

"Many opponents of the leadership were young, well-educated and impeccable officials," states Vladisavljević in the book.

"Their conflict was inevitably, although probably unfairly, seen more and more as a conflict between the old guard, the old-fashioned, clannish and unsuccessful leadership and those who represented the future of Montenegro."

Đukanović, Bulatović and Marović were then talked about as "young, beautiful and successful" representatives of the new political generation.

They wore sweaters and jeans, not suits like the old communist leaders, the media pointed out.

"They were people from the university, mostly from the socialist youth council at the time, who had somewhat different experiences and knew and believed that they could make the transition of the system in the direction required by that time," says Milica Pejanović Đurišić.

Milošević and other officials from Serbia immediately, already in October, strongly supported the opponents of the Montenegrin leadership.

In practice, this meant favorable coverage of the protests in the media under their control, which is not at all insignificant because the majority of people in Montenegro were informed more through Belgrade than local media, states Vladisavljević.

"But resistance to the leadership of Montenegro came primarily from internal sources, it had deep roots in political institutions and the population as a whole," he writes.

Act Two: January 1989

The silence did not last long.

As soon as the New Year's table was set, those who had left the streets of Podgorica in October of the previous year, met on the 5th of Yuanar at one table.

"I stand up and say 'my friends, January 7th is Christmas, if we rose up then, it would be a disaster and a great misfortune, because they would characterize us as Chetniks, and they already call us that.

"'We will go to work on Monday morning, and on Tuesday, Montenegro will rise to its feet' with an oath over the icon of St. Demetrius, the Bible and the Holy Scriptures that, whoever betrays, nothing will be left of him", recalled the union leader Pavle Milić.

It only took half an hour for them to arrive at the company on January 10 Radoje Dakić "they rush to the gate" and head towards the city center, says Milić.

"When we appeared in front of the assembly in October, our demands were only of a socio-economic nature, and at that time everyone in the protest committee was from Radoje Dakić", recalls Milić's colleague Milan Vukčević, proudly pointing out that he "spent a whole century" in that company.

"In January, we were a minority, and the main part of the protest was presented by Momir and Pavle Bulatović, Aco Đukanović, Milica Pejanović and others, and the demands were the resignation of officials."

The two Bulatovićs, Đukanović and Pejanović will later become high-ranking officials of the future Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), a party created from the Union of Communists of Montenegro.

A day later, on January 11, Montenegro stopped completely, it was effectively a general strike, writes Nebojša Vladisavljević.

The republican leadership resigns.

"There are people who believe that on January 11, 1989, we 'cowardly capitulated' and that we 'surrendered,'" said Marko Orlandić later, then a member of the Presidium of the VK SKJ.

"And what was needed and what could have been done in those days of upheaval? To use armed force against one's own people to defend the government? I don't know a Montenegrin official from that period who would have decided to do something like that."

Montenegro after the Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution

The new generation, which was fighting on the streets of Titograd, will first distribute party and then state functions.

Momir Bulatović he first became the president of the Presidency of the Central Committee of the Union of Communists of Montenegro, the highest party body, and after the first multi-party elections in 1990, also the president of the Presidency of Montenegro.

When the Union of Communists of Montenegro was transformed into the Democratic Party of Socialists, Bulatović was its first president.

Milo Djukanovic already in 1988 he was the youngest member of the Central Committee of the Union of Communists of Yugoslavia, and at only 29 years old, in 1991 he became the Prime Minister of Montenegro - the youngest in Europe.

The anti-bureaucratic revolution thus changed the way individuals are elected to high positions, states political scientist Nebojša Vladisavljević.

Instead of building a career for decades, with mandatory membership in the Communist Party, many suddenly jumped into high politics.

When the war started in Yugoslavia in 1991, there was no conflict between the Serbian head of state, Slobodan Milosevic, and the Montenegrin leadership - on the contrary.

Montenegrin soldiers, then part of the Yugoslav People's Army, participated in the months-long siege of the Croatian city of Dubrovnik, and Đukanović said at the time that "he hated chess because of the chessboard".

The checkerboard is a symbol in the middle of the Croatian flag.

"A free Milošević is the best thing that could happen to Yugoslavia at this moment, when the vampirized fascist forces in Croatia and Slovenia are trying to destroy everything that was created from 1945 until now.

"I am proud that in these historical moments I can be side by side with him in the defense of the achievements of the revolution," Đukanović stated in 1990 for Illustrated Politics.

Đukanović and Bulatović will come into conflict over the role of Slobodan Milošević in 1997, which will end with the division of the DPS.

Đukanović publicly criticized Milošević for the first time, calling him "a man with an outdated political philosophy, who is surrounded by corrupt assistants".

Bulatović remained the president of Montenegro until 1998, then he was the president of the FRY until 2000, but during the 2019s he did not have a significant political role until his death in XNUMX.

Đukanović will remain in power, rotating the office of prime minister and president, until 2023, when he was defeated by Jakov Milatović in the presidential elections.

Svetozar Marovic, the last member of the "triumvirate", was arrested in 2015 in Montenegro on charges of corruption and was found guilty in 2017.

However, Marović previously defected to Serbia, where he is still today.

Montenegro has been asking for his extradition for years, which still hasn't happened, which is one of the big problems in the relationship between the two countries.

Milica Pejanović immediately after the Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution, she did not hold any office - she said, she had other priorities.

Three decades later, Montenegro's attitude towards the war and the breakup of Yugoslavia is one of the reasons why the Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution is not viewed positively today.

"Another thing is the transition of the system, which was not what we expected... Although the question is what was realistic in such circumstances.

"Certainly, a large number of people became passive after that, it was felt that we do not have the strength in politics that we assumed we had," says the former ambassador of Montenegro to the United Nations, UNESCO, France and Monaco, as well as the former minister of defense.

Nebojša Vladisavljević also writes in "Antibureaucratic Revolution" that many participants in the demonstrations, such as local officials, company directors, and even union leaders, after all "encouraged demobilization" from the protests.

"Co-opted into the leadership, they eagerly awaited the chance to act within political institutions, as well as to use the privileges of their new status," says the professor of the Faculty of Political Sciences.

Marko Pejović from the non-governmental organization UZOR sees the "strengthening of divisions" and nationalist rhetoric as one of the key problems of the AB revolution.

"The three-decade period behind us in which power was reflected in one party denies that it was really an anti-bureaucratic revolution," says a political analyst for the BBC in Serbian.

"The main complaint against former managers was that they used official lunches and ate lamb... Whatever happened afterwards, we would celebrate those people today."

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter i Viber. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

Bonus video: