"Did you feel the shaking this morning?" Dušan Davidović, a pensioner from Kotor, asks a friend and a waitress at a buffet near his building.

It alludes to the earthquake near Nikšić that shook the ground in the Bay of Kotor a little earlier on April 3, 2024.

"I am, but I'm not," answers the woman dressed in black with a tray in her hand, while she gently waves the other with a sigh, then nods affirmatively to Dušan's "mint tea" and my "homemade coffee".

"We did well, I'm always afraid after that earthquake in 1979," Davidović tells me, then he returns the film to April 15 of that year.

At that time, he lived in the Byzantium Palace, a well-known building at the very entrance to Kotor's old town, and that Sunday morning at 7.19:XNUMX a.m. he was awakened by a noise and an earthquake he had never experienced before.

"At first I thought 'this won't happen to us' because a few days before there was a minor earthquake and I pulled a pillow over my head, but then the plaster in the apartment started to fall off, so I got up and from the window I saw the clock and the tower across the street falling apart, as well as the Prince's Palace behind.

"There was a lot of dust, the whole square was destroyed, it was creepy, there was panic, and people were going outside in their pajamas and running away from the city," 76-year-old Davidović recalled for the BBC in Serbian.

- From ruins to "city of solidarity": How earthquake-ravaged Skopje reconciled the world during the Cold War

- Earthquake in Albania: Durrës - the epicenter of grief

- "The moans and cries were terrifying and many stayed outside all night" - testimonies about the earthquake in Croatia

An earthquake measuring seven degrees on the Richter scale hit the Montenegrin coast 45 years ago and claimed 101 lives, while another 35 people died in Albania.

The epicenter was in the Adriatic Sea, 15 kilometers from the coast between Ulcinj and Bar, according to the website of the Institute for Hydrometeorology and Seismology of Montenegro today.

Almost all the cities on the coast suffered, 250 settlements were destroyed, 64.000 buildings were damaged, as well as 550 kilometers of roads and parts of the Belgrade-Bar railway.

This earthquake was "the strongest recorded earthquake in Montenegrin history", says Jadranka Mihaljević, head of the Department of Instrumental and Engineering Seismology of the Institute of Hydrometeorology and Seismology of Montenegro, for the BBC in Serbian.

"It is also the strongest instrumentally recorded earthquake on the eastern Adriatic coast.

"If we talk about earthquakes whose strength we judge indirectly, through historical records, only the one that hit Dubrovnik in 1667 and which is considered to have a magnitude of 7,4 on the Richter scale was stronger," explains the seismologist.

- Earthquakes in the Balkans: Why do they shake so much?

- Are there seismologists in the Balkans to measure the power of earthquakes?

- Can technology predict earthquakes?

From Ulcinj to Herceg Novi, 'everything rocked'

Unlike Davidović, his peer Ismet Karamanaga from Ulcinj was not woken up by the earthquake.

When the clock struck 7.19:XNUMX, this resident of Ulcinj's Old Town, who was then teaching German at the local school, had already descended under the walls, right next to the coast.

"I started to paint the boat, and when it started shaking, I ran back home because rocks started falling around me," recalls Karamanaga, whom the people of Ulcinj jokingly call "the mayor of the Old Town".

With his wife and 17-month-old son, he ran out of the house towards the exit of the fortress. he remembers for the BBC in Serbian

"Everything around my house was in ruins, our garden was in disarray, smoke and dust were rising, but the house survived and was later marked with yellow paint, which meant that it could be rebuilt," he adds.

Five people died in the "completely destroyed" old town, among them Ismet's friend.

A total of 31 victims have been confirmed in the city and its surroundings.

His fellow citizen Mustafa Canka, who is two decades younger, still lives today, as in 1979, in the Nova Mahala neighborhood, in the center of Ulcinj.

He still remembers the "very nice weather" that morning and the basketball game he played with his younger brother in the yard of the family house, but instead of one of the two boys winning, it was interrupted by an earthquake - at first a slightly weaker one.

"After 18-19 minutes, the strongest earthquake starts, my father grabs me by the shirt and we fly out the door, and my mother, who is nine months old, jumps out the window with her brother.

"Baba stayed inside and, I remember like it was yesterday, she was standing and holding the television so that it wouldn't fall from the shaking display case," recounts the writer and journalist from Ulcinj for the BBC in Serbian.

"It seemed to last forever."

- How an earthquake that did not happen was recorded in Valjevo

- Petrinja, a month later - what Andrić, Selimović and Krleža say from the ruins

- Earthquake in Croatia: "I would never leave my animals behind"

About thirty kilometers to the northwest, in Bar, seven-year-old Draginja Radonjić was hiding under the door of her mother's room with her sister.

"It lasted about ten seconds and the feeling was awful and it seemed like it would never stop.

"Even now I remember the shaking well, but above all the screeching and sounds that our building made," the 52-year-old historian told the BBC in Serbian.

When the impact stopped, the escape from the buildings of the then newly built complex began.

"My mother caught my younger sister, and I was caught by the neighbor from the floor above, who was rushing past us, and it seemed to me that we came down from the sixth floor in a second and a half!

"When we got our hands on the ground and the clear sky, it was a different feeling right away," recalls Radonjić.

The city of Bar, with 49 victims, mostly in villages in the hinterland, was the most affected place in Montenegro.

The Port of Bar, which was renovated at the time, suffered great damage, as did the Belgrade-Bar railway, one of the most important roads in that part of Yugoslavia.

The total damage amounted to "about one billion dollars" in this port city, says Draginja Radonjić.

When hotel after hotel collapses

Although Bar and Ulcinj were the closest to the epicenter of the earthquake and had the most victims, huge damage was also suffered by Budva, where several hotels collapsed, next to which the family of Željko Filipović lived.

At that time, the 21-year-old young man was in the apartment with his father, and around him the Slavija, Stara and Nova plaža hotels were falling one after the other, Željko recounts for the BBC in Serbian.

"The earthquake woke me up, we found ourselves immediately in front of the building, we see that the hotels have fallen and we hear the waitress screaming from under the ruins of Stara Plaža, stuck under the door.

"We only managed to open a small hole, just enough to pull her out and she stayed alive," recalls the 66-year-old from Budva.

The total damage after the earthquake "was not less than 4,5 billion US dollars at that time," says Božidar Pavićević, an expert in seismic engineering and then director of the Republic Institute for Urban Planning and Design of Montenegro.

Prema according to data from the US Federal Reserve Bank (Fed), that is equivalent to about 19 billion US dollars today.

To work in the ruins

Immediately after the earthquake, Dušan Davidović rushed out of his apartment in Kotor with his family.

The daughter, wife and father ran out into the street in their pajamas and housecoats, and they all went to their father and mother-in-law in Dobrot, a settlement on the outskirts of Kotor.

"I knew that as a journalist I still had work to do, so I got fully dressed and was the last to leave, I remember even putting a cap on my head," he explains today with a laugh.

The interruption of telephone and radio connections for the then correspondent of RTV Titograd meant that there was almost no way for him to share the news about the city's suffering with the newsroom.

"An experienced and witty journalist of Radio Titograd knew that across the road from the former RTV Titograd was the headquarters of the company for the roads of Montenegro, and in every major town there were small trucks with radio communication.

"Through the militia, he asked to find me, so I sent the first press report from Kotor via walkie-talkie," says Dušan, while his deeply wrinkled cheeks break into a smile.

- Seven factors that make earthquakes deadly

- What are faults and how do they affect earthquakes?

- How long can you survive under the rubble after an earthquake

- Do you also have a bag full of unnecessary things?

Tito in Igalo and Yugoslav solidarity

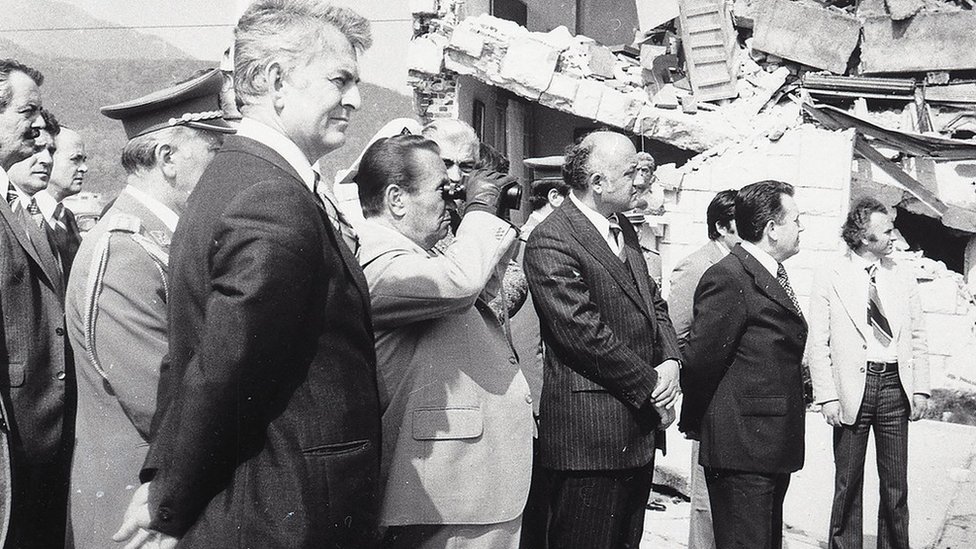

While the Montenegrin coastline was shaking and collapsing, the Yugoslav president for life, Josip Broz Tito, was staying in its extreme northwest.

That April, a year before his death, he stayed in the villa "Galeb", a summer residence in the Igalo spa, on the outskirts of Herceg Novi.

A few hours after the earthquake, Tito asked to go to the Riviera and check the situation, said Alen Filipović from the "Dr. Simo Milošević" Institute, today the owner of this facility, for television N1.

"Tito didn't want to be evacuated, as they suggested, but he asked for a tent to be set up in the yard, near the apartment," said Filipović.

He left Dubrovnik airport for Belgrade only the next day.

Davidović remembers that Tito visited some of the most damaged areas in Boka Kotorska.

"They brought him from Igalo to the shipyard in Bjela, where a gruesome video was made, a real horror.

"Then they took him to Kamenar, but at one pass on the way to Herceg Novi, the road was cut off, an entire house fell into the sea, the ground was even collapsing a little more and it was impossible to go any further," says Davidović.

The presence of Broz, as well as his words from Montenegro, which were broadcast by the press, television and radio stations, echoed throughout the country.

That "helped a lot to start solidarity in Yugoslavia" and the aid reached the Montenegrin coast very quickly, says Draginja Radonjić.

On the same day, water arrived in Bar by tanker from Dubrovnik, and tents, blankets and food were delivered by trucks to all the affected towns, Radonjić remembers.

"For years, the population of all Yugoslav republics set aside a small percentage of their income to help Montenegro, it seems to me one percent or one daily wage.

"Serbia was especially at the forefront of this: I found information that for 15 years, people from Serbia were separating these funds, practically until the collapse of the great Yugoslavia," says Radonjić.

Slobodan Mitrović, who was caught by a natural disaster in Podgorica, but was later in his native Budva during the reconstruction, considers the help to Montenegro "a great humanitarian moment".

"I believe that this would not happen today, because then there was the spirit of the Yugoslav state, a sense of solidarity and togetherness", believes the architect from Budva.

The story of solidarity after the earthquake in Albania in 2019:

How did the earthquake happen?

Montenegro is located in the area where the Adriatic massif and the Dinaric mountain massif meet.

That encounter sometimes leads to earthquakes, explains seismologist Jadranka Mihaljević.

"The Adriatic plate sinks under the Dinarides, which rise due to that pressure, so at one point that stress in the rocks exceeds the limit of strength and there is a great release of energy," he says.

The Dinaric massif is divided into blocks, and the settling of individual blocks, she says, was related to subsequent seismic activity throughout 1979.

By the end of 1979, 90 aftershocks of magnitude four on the Richter scale or greater, more than 100 between magnitudes 3,5 and 10.000, and nearly XNUMX smaller aftershocks had been recorded. it is stated on the website of the Montenegrin Institute for Hydrometeorology and Seismology.

The strongest was recorded in front of Budva, 6,1 degrees on the Richter scale, in May, says Mihaljević.

"The earthquake was accompanied by landslides and landslides on land and below sea level, as well as sand eruptions in the area of the Bojana River and Boka Kotorska.

"The process of settling the soil in Montenegro continued years later, and all subsequent earthquakes were the result of that large release of energy in one moment," says the seismologist.

However, the number of victims was lower compared to experiences from earthquakes of this magnitude.

"Fortunate circumstances also had an effect: it was not the tourist season, it was Sunday, early in the morning, office buildings and schools were not open," explains Mihaljević.

- What houses and buildings in Serbia must have in order to withstand an earthquake

- Earthquakes, floods and fires: How to behave

- Why earthquakes in Turkey were so devastating and deadly

- Why buildings in Turkey fell like houses of cards

'Dobroshake'

Despite the 31 victims on the territory of Ulcinj and the enormous cultural and material damage caused by one of the biggest natural disasters in the history of the city, Mustafa Canka calls it a "good shake".

"Already after four or five years, the city was like new, much better than before the earthquake, because better and better quality houses were built, and the infrastructure was significantly renovated.

"We gained stability from a temporary instability: the ground shook well and sent us a message that we should be aware of the enormous force of nature that can turn everything into wasteland and ashes at any moment," he concludes.

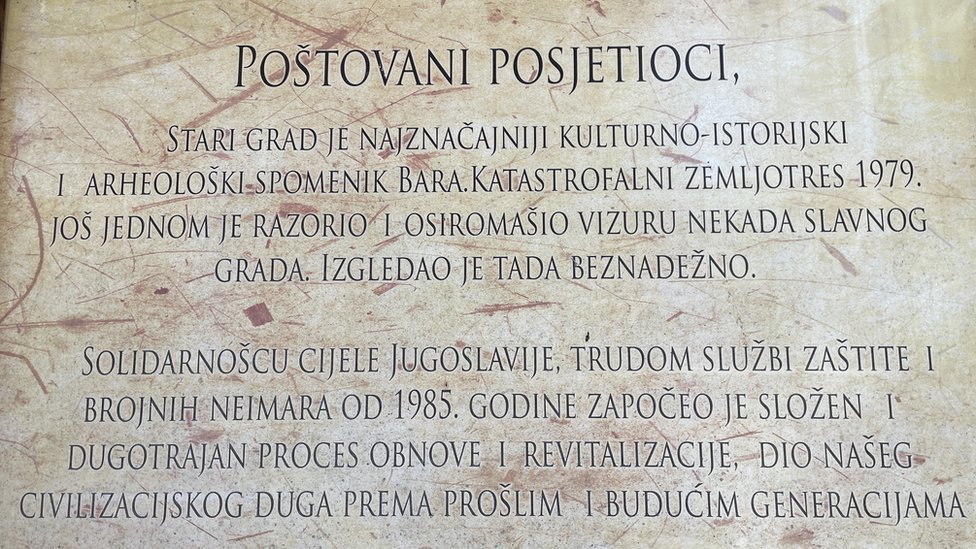

For Bar, the earthquake was a "flywheel for growth", even though the old town, port, hotels, roads and railway were extremely damaged, says historian Radonjić.

"In those ten years, it changed a lot, it grew rapidly, got new outlines of a real Mediterranean city, wide streets and boulevards, a renovated port, which makes it different from others on our coast," says Radonjić.

The earthquake gave birth to "the first radio station in the city, Radio Bar", launched two days after the earthquake to inform fellow citizens, and "it still exists today", the historian points out.

Although "about 30 percent of the buildings" in Budva's old town were destroyed, the restoration of the Mediterranean fortress, within whose walls there were no inhabitants for 10 years, somehow "healed" this centuries-old building, says architect Slobodan Mitrović.

Before the earthquake, the old town was "almost unusable, almost none of the houses were healthy, there was no hygiene, electric cables were everywhere in the streets and there was no sewerage," says Mitrović, one of its hundreds of remaining residents.

"The spirit of the city was disturbed due to the earthquake, the new construction gave a new quality of life in the old city, improved hygienic conditions, waterproofing and thermal insulation.

"During the renovation, an early Christian basilica from the fifth and sixth centuries, ancient gates from the fourth century BC, a Roman pavement and thermal baths were also discovered, which contributed to the knowledge that Budva was an important ancient city," says the architect.

But the renovation also had a negative side, which Mitrović considers one of the reasons why Budva was not included in the UNESCO world heritage.

"The price of all this is the loss of the spirit of the old town: Budva today does not have any really old doors or windows, something that would bring an aesthetic or cultural dimension, but the current state only imitates the former," Mitrović believes.

The earthquake also contributed to the development of the seismological network in Montenegro, since in addition to one existing station in Podgorica, nine more were built shortly after the earthquake thanks to a grant worth 450.000 dollars.

"It was interesting that in the report Reducing Seismic Risk in the Balkan Region from 1984, they stated that few earthquakes in the world like this Montenegrin one triggered such a wide range of seismic risk reduction activities.

"One of the good achievements of the earthquake was the establishment of the Faculty of Civil Engineering in Podgorica, where the subject of seismic engineering was introduced," says Jadranka Mihaljević.

The concept of seismic risk is introduced into design, which is calculated mathematically and applied in practice, says Božidar Pavićević, former professor of this faculty.

"You know the bearing capacity of the terrain, the amount of space that can support a certain construction of buildings," he explains.

Pavićević was in the team for the assessment of damage to 64.000 buildings on the coast and the development of the spatial plan of Montenegro, which was supposed to guarantee greater resistance to natural disasters.

Adolf Ciborovski, a Polish architect who played an important role in the construction of Skopje after the devastating earthquake of 1963, in which 1.070 people died, also worked with them.

But this project does not include the capital of Montenegro, says Pavićević.

"When Ciborovski was leaving in 1984, he told me that everything we did hangs in the balance until there is a general plan for Titograd.

"The spatial plan was in force until the beginning of the 21st century, but it was abandoned in 2005, and what was awarded on the coast and in Podgorica is not included today," warns the retired professor.

Because of this, as well as the density of population in today's coastal cities of Montenegro, a similar natural disaster could have far greater consequences, he estimates.

- The secret of the Ezgi building and the long investigation of a mother: Earthquake in Turkey, one year later

- The strongest earthquake in Taiwan in the last 25 years, there are dead, hundreds injured

Although he did not experience an earthquake like the one in 1979, for Dušan Davidović its consequences are still felt.

After a temporary move to Dobrot, in 1981. In XNUMX, he hid himself with his family in a solitaire in the Rakite settlement in Kotor, he says, pointing from the cafe's garden to a building a few tens of meters away.

The old town of Kotor became part of the cultural and natural heritage of UNESCO in October 1979.

Before the earthquake, between 2.000 and 3.000 people lived in the old town throughout the year, and tonight "not even 300 people will sleep, including tourists, Turks, English, Russians, Serbs, Montenegrins - all together," Davidović says sadly.

"I never returned to the Old Town after I left on the day of the earthquake.

"I may have slept over a few more times at a friend's place, just to get over my desire," says Kotoranin with a slight smile.

See also this story:

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube i Viber. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

Bonus video: