Warning: This story contains details of violence, including sexual violence, which some readers may find disturbing. The name of one of the interlocutors - Ravi - has been changed to protect his identity.

"They took off my clothes, made me sit on a chair and gave me electric shocks in my leg. I thought that was the end."

Ravi went to Thailand for a job in the IT sector, but instead of sitting in a high-rise office building in Bangkok, the 24-year-old from Sri Lanka ended up imprisoned in a camp in Myanmar.

He was kidnapped and smuggled across the river near the Thai border town of Mae Sot.

There, he says, he was sold to one of the many labor camps run by gangs whose members speak Chinese and engage in Internet fraud.

They force trafficked victims like Ravi to use fake internet identities, posing as women, to con single men in the United States (US) and Europe.

The targets of the fraud are then convinced to invest large sums of money in fake e-commerce platforms that promise quick profits.

- How a million dollars was won in the "pig slaughterhouse", an online love scam

- "We've Got Your Porn Collection": The Rise of the Blackmail Hacker

- "He forced me to do things a child shouldn't": The Omegle case and child abuse

The internet fraud labor camp where Ravi was housed is hidden in the jungle in Mayawadi, an area not under the direct control of Myanmar's military government.

Thousands of young men and women from Asia, East Africa, South America, and Western Europe are lured into these camps run by cybercriminals with promises that they will actually work in computer jobs, Interpol announced.

Refusal to order is punished by beating, torture or rape.

"They put me in a cell for 16 days because I was disobedient.

"They only gave me water mixed with cigarette butts and ash to drink," Ravi told the BBC.

"During the fifth or sixth day, they brought two girls to a nearby cell.

"They were raped by 17 men in front of my eyes," he adds.

"One was a Filipina.

"I don't know what nationality the other victim was".

Who are the victims of human trafficking?

In August 2023, United Nations (UN) estimated that more than 120.000 people in Myanmar and another 100.000 in Cambodia are forced to engage in these and various other online scams - from illegal gambling to cryptocurrency scams.

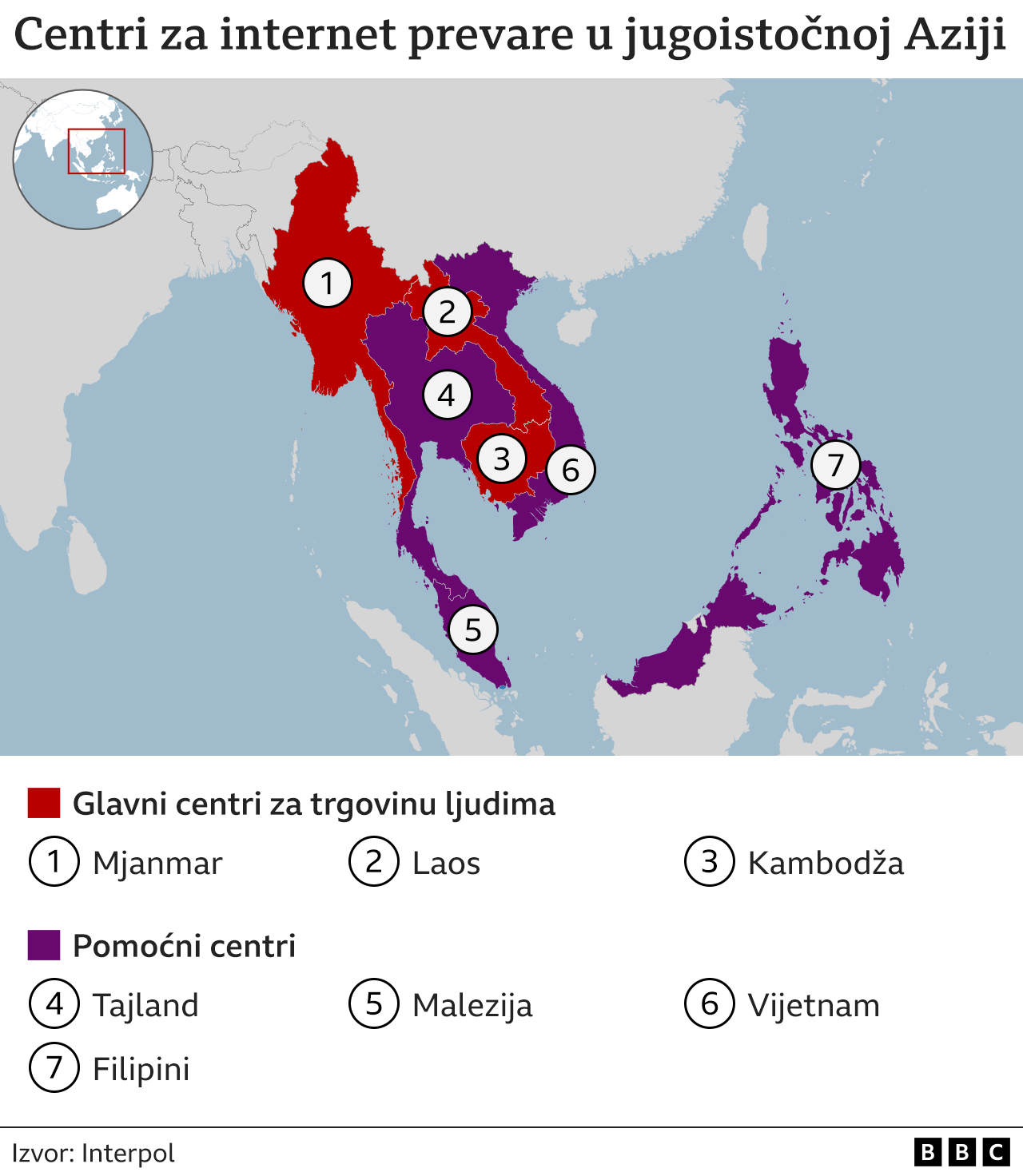

An Interpol report last year said new centers for internet fraud were discovered in Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand and, to a lesser extent, Vietnam.

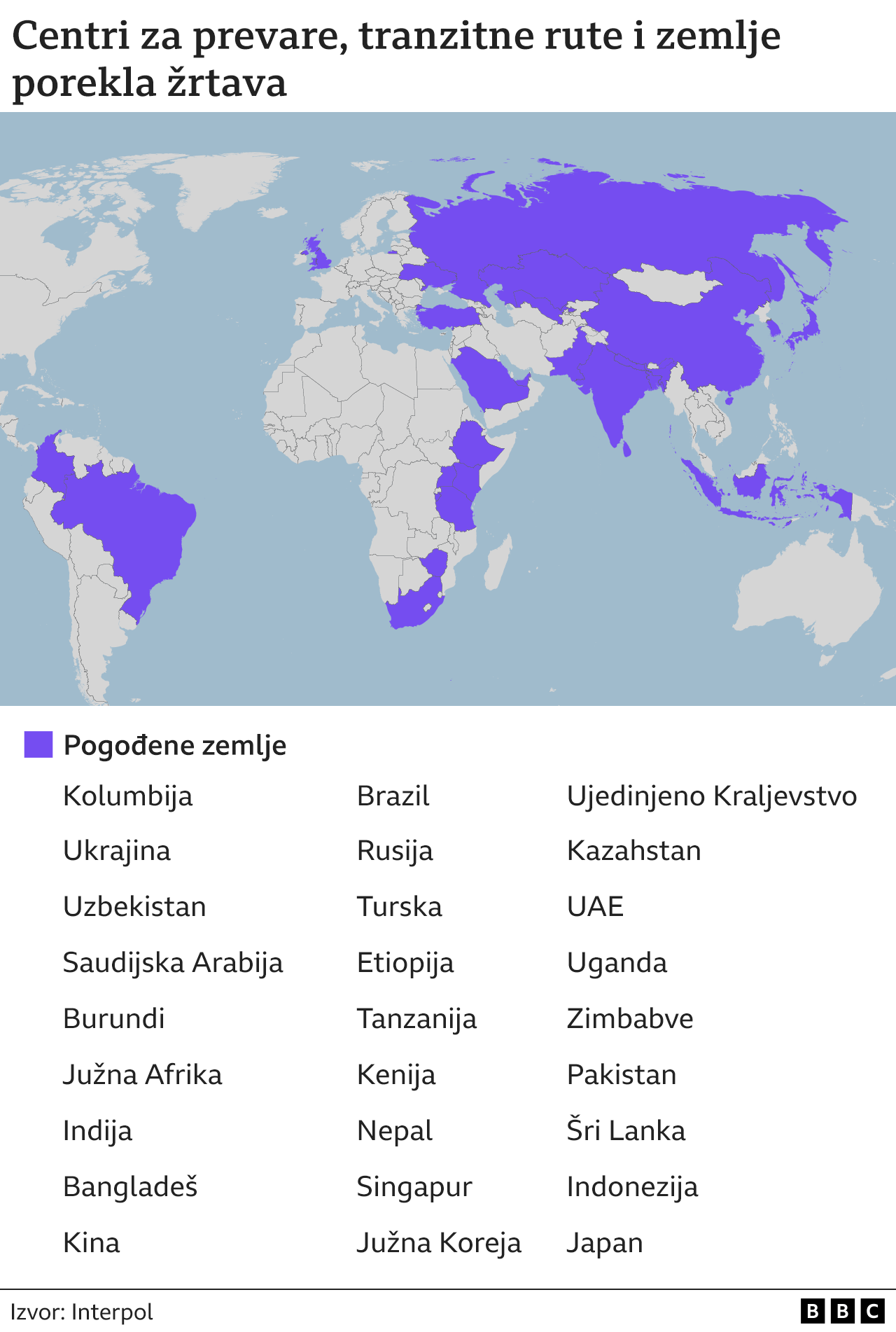

An Interpol spokesman told the BBC that this trend has grown from a regional issue into a global security threat, and that many other countries are also involved - as centers of fraud, transit routes or as countries from which victims of human trafficking come.

The Indian government announced in early April that it had so far rescued a total of 250 of its nationals who had been smuggled into Cambodia, and in March China returned hundreds from fraud centers in Myanmar.

Beijing is also increasing pressure on both Myanmar's military government and armed groups to close these centers.

Sri Lankan authorities know that at least 56 of its citizens are being held captive in four different places in Myanmar.

However, Sri Lanka's ambassador to Myanmar, Janaka Bandara, told the BBC that eight of them were recently rescued with the help of the Myanmar authorities.

Those who manage these camps have a constant supply of migrant workers who are their target group.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of engineers, doctors, nurses, and IT professionals from South Asia leave the countries in search of work abroad.

Ravi, an IT professional, was desperately trying to leave Sri Lanka when he found out about a local broker offering a data entry job in Bangkok.

The intermediary and his associate in Dubai assured him that the company would pay him a basic salary of around $1.200.

Ravi and his wife, who had recently married, believed that their new job would allow them to build a house, so they took out loans to pay for the services of a local realtor.

- What is "revenge pornography" and how does it affect victims

- Revenge pornography in Serbia - how to protect yourself from digital bullies

- "I was raped at the age of 14, and the video ended up on a porn site"

From Thailand to Myanmar

In early 2023, Ravi and a group of other people from Sri Lanka were sent first to Bangkok and then to Mae Sot, a city in western Thailand.

"We were taken to a hotel, but we were soon handed over to two armed men.

"They took us to Myanmar, across the river," says Ravi.

They were then transferred to a camp run by Chinese-speaking gangs, and were specifically ordered not to take photos.

"We were terrified.

"Around forty young men and women, among whom were citizens of Sri Lanka, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and African countries, were forcibly detained in the camp," he said.

Ravi says escape was impossible because the camp is surrounded by high walls and barbed wire, and armed guards watch the entrances 24/7.

Ravi emphasized that everyone was forced to work up to 22 hours a day and only had one day off a month.

They were expected to find at least three male targets each day.

Those who disobeyed orders were beaten and tortured, except for those who paid for their freedom.

The man who did just that is Neil Vijay, a 21-year-old from the western Indian state of Maharashtra, who was smuggled into Myanmar in August 2022 along with five other Indians and two Filipino women.

He told the BBC that his mother's childhood friend promised him a job at a customer service center in Bangkok and that he charged them $1.800 for the service.

"There were several companies run by people who speak the Chinese language.

"They were all frauds.

"We were sold to those companies," Neal says.

"When we got to that place, I lost all hope.

"If my mother had not paid their ransom, I would have been tortured like the others."

Because he refused to be involved in the scams, Neal's family paid the gang $7.190 to free him, but he was in the camp long enough to witness the brutal punishment of people who either failed to meet targets, or could not afford to pay the ransom.

After his release, Thai authorities helped him return to India, where his family filed a lawsuit against local intermediaries.

Thai officials are working with other countries to help victims return to their countries.

However, a senior official at Thailand's Ministry of Justice told the BBC that compared to the number of people forcibly detained in camps in neighboring countries, the number rescued was very small.

"We need to establish better communication with the world, to inform people about these criminal gangs so that they do not become victims," said the deputy director general of Thailand's Special Investigation Department, Piya Raksakul.

Human traffickers often use Bangkok as a tourist hub in the region, he says, because people from many countries, including India and Sri Lanka, travel to Thailand on visas that are issued on entry into the country.

"So these criminals use and smuggle people to work for them," he adds.

How people are deceived?

The targets are rich men, especially in Western countries, with whom romantic relationships are established through other people's stolen phone numbers, social media accounts and messaging platforms, says Ravi.

Detainees made direct contact with victims, usually leading them to believe that the first message - often just a "hello" - was sent by mistake.

Some ignored the messages, but lonely people or those looking for sex would often get caught, Ravi explains.

Once they established a relationship, a group of young women in the camp would be forced to make explicit videos, further drawing the target into the scam.

After exchanging hundreds of messages in just a few days, the scammers would gain the trust of their targets and convince them to invest large sums of money in fake e-commerce platforms.

The fake apps then display fake investment and profit data.

"If someone deposits $100.000, we give them back $50.000, representing it as their profit.

"So now it looks like they have $150.000, but in reality they only get half of their initial investment of $100.000, and the other half stays with us," explains Ravi.

Once the scammers have taken as much money as they can from the victims, the messaging accounts and social media profiles are deleted.

It is difficult to estimate the extent of such scams, but in the report on Internet crime for the year 2023, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI - criminal investigation and intelligence agency of the USA) states that in America there were more than 17.000 complaints about the violation of confidentiality of data and fraud on dating sites, and the losses amounted to 652 million dollars.

- When they "dipfake" you: "They pasted my face on a porn video"

- Privacy protection in the age of social networks

- "I was deepfaked by my best friend"

- New danger of artificial intelligence: It is used to make sexual photos of children

Psychological and physical scars

After a month in captivity, Ravi says he was sold to another gang because the "company" he originally worked for "went bankrupt."

During his six months of captivity in Myanmar, he did forced labor for a total of three gangs.

He told the new gang that he could no longer deceive the people and begged them to let him go back to Sri Lanka.

One day he clashed and fought with the leader of the team, after which they took him to a cell and tortured him for 16 days.

Eventually the "Chinese boss" came to see Ravi and gave him "one last chance" to work again - because of his knowledge of software.

"I had no choice, half my body was already paralyzed," says Ravi.

For the next four months, Ravi managed Facebook accounts that were opened using a virtual private network (VPN), artificial intelligence applications and 3D video cameras.

Meanwhile, Ravi begged to be allowed to visit his sick mother in Sri Lanka.

The gang leader agreed to release him if he paid a ransom of $2.000 and an additional $650 to cross the river and enter Thailand.

He got the money from his parents who mortgaged their house, and Ravi was transferred to Mae Sot.

Because of the $550 fine he had to pay at the airport for not having a visa, Ravi's parents took out another loan.

"When I arrived in Sri Lanka I was $6.100 in debt," he says.

He returned home, but he hardly sees his wife, whom he recently married.

"I work day and night in the garage to pay off the debt.

"We pawned both wedding rings to pay the interest," Ravi says bitterly.

Also watch this video:

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube i Viber. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

Bonus video: