The true extent of clinical research during which infected blood was given to children in the 1970s and 1980s has been revealed after the BBC obtained access to medical documents.

They reveal the secret world of unsafe tests on children from Great Britain and show that doctors put scientific goals before the needs of patients.

The research lasted more than 15 years, involved hundreds of people, and most of them were infected with HIV or hepatitis C.

One of the surviving patients told the BBC that they were treated like "guinea pigs".

Among the research participants were children with blood clotting disorders, and in many cases their families did not give their consent.

Most of the children subjected to these tests are dead today.

- How 175 British children were infected with the HIV virus

- School of Death - the biggest health disaster in British history

- HIV can be removed from cells, scientists claim

The documents show that doctors at haemophilia treatment centers across the UK used blood products, even though they were known to be possibly contaminated.

A shortage of blood in this European country during the 1970s and 1980s prompted doctors to import it from America.

High-risk donors, such as prisoners and drug addicts, gave plasma for this therapy, and it was contaminated with viruses such as hepatitis C and HIV, which can be fatal.

Hepatitis C attacks the liver and can lead to cirrhosis and cancer.

The factor 8 blood product proved to be very effective in stopping bleeding, but was known to be infected with viruses.

A public inquiry into this scandal is ongoing, and the final report is expected in May.

'Guinea Pigs'

Luke O'Shea-Phillips, now a 42-year-old man, has a mild form of hemophilia, which is a blood clotting disorder, and he bleeds and bruises more often than other people.

He contracted hepatitis C, a virus that can be fatal, while being treated at a central London hospital, where he was admitted in 1985 for a small cut in his mouth aged just three.

He was knowingly given a blood product, which his doctor knew could be infected, just to participate in scientific research, according to documents obtained by the BBC.

Doctors wanted to find out how likely patients were to contract diseases from the new version of the heated factor 8.

This substance was also given to Luke to stop the bleeding in his mouth, even though he had not been treated for the disease until then.

- Hepatitis in children: What kind of disease is it and what is the situation in Serbia and in the world

- "The most expensive drug in the world" gives hope to hemophilia patients in Serbia

- The press conference that changed the world - the day Magic announced that he was HIV positive

A letter from his doctor, Samuel Machin, to another hemophilia specialist became evidence in a public inquiry into the tainted blood scandal in Great Britain.

Writing to colleague Peter Kernoff at the Royal Free Hospital in London, Machin detailed the treatment Luke and another boy received.

"I hope they will be suitable for your research into heating factor treatment," he added.

A few months earlier, Kernoff called on colleagues in his specialty to find patients who might be suitable for the study.

He especially emphasized that they must not be "pre-treated", for which the name "PUPs" was used in the medical community in Great Britain (Previously untreated patients).

Those patients were also called "innocent hemophiliacs", and this term was also written down by Doctor Macin in Luka's hospital record.

"I was a guinea pig in tests that could have killed me," Luke told the BBC.

“There's no other way to explain it - my treatment was changed to take part in the research.

"That change gave me the deadly disease hepatitis C, although my mother was never informed about it," says the 42-year-old.

As he says, "for the scientific world, the fact that he was an 'innocent hemophiliac' was an incredible advantage."

"As a pure specimen on the basis of which scientific knowledge can be obtained, I was a part of it without hesitation," adds Luk.

In the following years, while the scientists were coming to their conclusions, Luk was subjected to numerous blood tests.

Doctors said they were monitoring his condition and during that period his mother Sheila O'Shea was grateful.

Kernoff and Machin published the results of their research in 1987 and concluded that this type of treatment had "little or no effect" on reducing the risk of hepatitis C.

Neither one nor the other doctor is alive today.

Before his death, Machin submitted evidence for a public inquiry and then confirmed that Luk was recruited for the research of his colleague Kernoff.

But he denied that this was carried out without the consent of Luke's mother.

"It was discussed with his mother, although I recognize that the standards of consent in the 1980s were quite different than today," Machin said.

Sheila O'Shea says she was "absolutely not informed" of the investigations.

"With an innocent three-and-a-half-year-old child, I would never consider such a thing.

"I would never allow my child to be part of an interrogation - never!" she said.

Documentation shows that doctors were aware that Luk had hepatitis C as early as 1993, but did not tell him until 1997.

One of the reports confirms this and states that "it was not discussed with the patient or his family".

After successful treatment, Luk no longer has hepatitis in his body.

See also this story:

'lab rats'

However, evidence from clinical trials has raised major concerns.

"The patient should always be given the best treatment and they should always give written consent - if those two things are not met then the trial would be considered very problematic," says Emma Cave, professor of healthcare law at Durham University.

Professor Edward Tudenham, who was a haemophilia doctor at the Royal Free Hospital in the 1980s, confirmed these fears.

When asked if he thought ethical standards were met during clinical trials in the 1980s, he simply replied, "No."

- Life and death with HIV: "No more burials in black bags, but there are in metal boxes"

- "Doctors in Serbia did not discover that I had HIV for a year"

- A patient called Nada - the body fought the HIV virus by itself

A BBC investigation revealed that Drs Mechin and Kernoff were among a community of doctors with similar research ambitions.

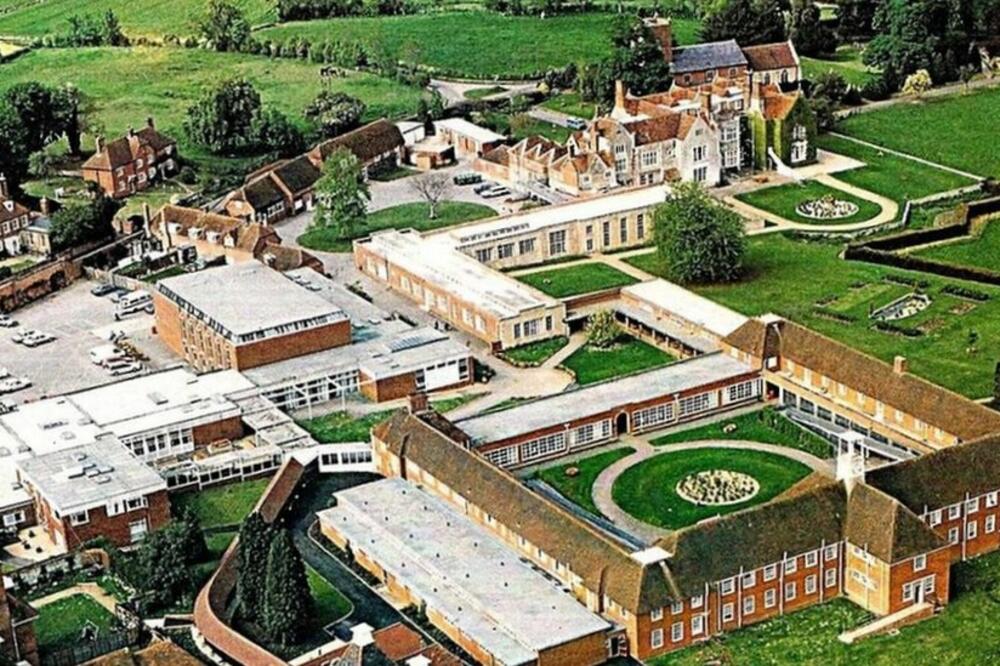

A special school near Alton, Hampshire, was attended by a large group of hemophiliac boys.

The school for children with developmental disabilities had an NHS haemophilia unit, so boys who had bleeding could be treated quickly and then return to school.

Their doctor, Anthony Aronstam - who has also died - used a "unique" group of boys for extensive clinical trials.

One series of experiments looked at whether using three to four times more factor eight than normal for a child would help reduce bleeding.

This was a preventive treatment, known as prophylaxis, involving repeated injections with infected factor VIII products and subsequent blood tests.

High concentrations of infected blood products were given to the boys without their - or their parents' - consent.

Of the 122 students who attended Treloar's College between 1974 and 1987. 75 have so far died from HIV and hepatitis C infection.

"Despite knowing the blood was infected with hepatitis, they started a trial that required us to receive far more than we needed," says Gary Webster, who was unwittingly a part of it.

"They treated us like laboratory rats.

"There were lots of studies we all took part in during the 10 years we were at the school," said Ade Gudjir, a student at Treloar's College from 1980 to 1989.

Controversially, another trial involved placebo treatments.

This meant that some boys, who thought they were given factor 8 to prevent bleeding, were actually given saline.

"When you think you've got therapy, it changes your behavior," Gary said.

"You run more, you play rougher in football. For a hemophiliac, you feel a bit invincible for a short time after the injection. But with a placebo, you're just risking your life by changing your behavior."

He told the BBC that they were punished at school if they missed injections.

"That would mean that their judgments were wrong and that we, the children, were forced to walk along that edge.

Dr. Kernoff's pursuit of clinical progress through research was rigorous, as was his hunt for suitable test subjects—puppies and innocent hemophiliacs—which resulted in those involved getting younger and younger.

A four-month-old baby was included in the study.

Among his studies was one that compared the infectivity of another blood plasma product - cryoprecipitate (cryo) - with factor VIII concentrates.

Cryo has been used to treat mild blood clotting conditions.

It contained factor 8 protein, but in lower concentrations and from fewer donors and was therefore considered less risky.

Dr Kernoff's search for suitable people led him to Mark Stewart, his brother and their father, as they all had very mild cases of von Willebrand's disease - another type of blood clotting disorder.

Their usual treatment was cryo.

As part of his test, Kernoff gave them all the Factor 8 concentrates instead.

"Until they gave us concentrates, once a month we would have a little nosebleed, we would go upstairs for cryo and that would be it".

All three are infected with hepatitis C.

Mark's brother and father died of liver cancer after the infection attacked this organ.

They were never told they were infected until it was too late to treat.

"Anger is an understatement," Mark said.

"Your dad's in the front carriage, your brother's in the second, and you're in the third - so you know what's coming. They will not deviate from that track. This is how hepatitis C works. It's going to get to you."

"We await the release of the contaminated blood results, which we hope will give our former students the answers they have been waiting for," Treloar said in a statement.

The investigation into the contaminated blood scandal will be completed on May 20.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube i Viber. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

Bonus video: