In December 1829, Lord William Bentinck, the first Governor-General of India under British rule, banned "sati", the ancient Hindu practice of sacrificing a widow by burning her husband on the funeral pyre.

Bentinck, then Governor-General of Bengal, sought the opinion of 49 senior army officers and five judges, and was convinced that the time had come to "wash away this ugly stain from British rule".

According to his law, sati was "opposed to the sentiments of human nature" and shocking to many Hindus, in addition to being "unlawful and depraved".

- Murders that shocked India: Ritual sacrifice suspected

- A woman was set on fire on her way to a hearing regarding a rape case

- Four Indians were executed for the rape and murder of a student

Under this law, those convicted of "aiding and abetting" the burning of a Hindu widow, "whether the victim was voluntary on her part or not," would be found guilty of capital murder.

It gave courts the power to impose the death penalty on people convicted of using force or assisting in the burning alive of a widow "who was stupefied and incapable of expressing free will".

The Bentinck Act was even stricter than the more gradual eradication of the practice proposed by leading Indian reformers campaigning against sati.

After the adoption of this law, 300 eminent Hindus, led by Raja Ramonhun Roy, thanked him for "saving us forever from the hideous stigma hitherto associated with our character as conscious murderers of women."

Orthodox Hindus resisted and wrote petitions against Bentinck.

Citing scholars and scriptures, they contested his argument that sati was not an "obligatory duty of religion".

Bentinck did not budge.

The authors of the petition appealed to the Council of State of the United Kingdom, the court of last instance in the British colonies.

In 1832, the Council upheld the law, saying that sati was a "flagrant insult to society".

"The unflinching belligerence of the 1829 Act was perhaps the only instance in 190 years of colonial rule that a social law was enforced without offering any concession to orthodox sentiment," points out Manoj Mita, author of Pride of Caste, a new book on the legal history of caste in India.

Also, Mita points out: "Long before Gandhi famously applied moral pressure against the British Empire, Bentinck applied the same force against the gender and caste prejudices that underlie sati."

"By criminalizing a native custom that harmed the colonized, the colonizer scored a moral point," he writes.

- Indian man killed woman - forced cobra to bite her

- How India is fighting street spitting and why the battle is impossible to win

- Indian teacher's big heart - donated hundreds of smartphones to help children learn

Thomas McCauley

But in 1837, Bentinck's law was relaxed by another Briton, Thomas Macauley, author of the Indian Penal Code.

According to McCauley's interpretation, if someone had evidence to support the claim that he lit the pyre at the insistence of the widow herself, then he could get away with a lighter sentence.

In the draft law, he pointed out that women who set themselves on fire may be motivated by "a strong sense of religious duty, sometimes also a strong sense of honor."

Mita concluded that Macaulay's "compassionate position" on sati had resonance among British rulers decades later.

He writes that his design was drawn from mothballs after the Mutiny of 1857, when native Hindu and Muslim soldiers, also known as sepoys, revolted against the British East India Company for fear of smearing bullet casings with animal fat, which their religion forbids.

The relaxed regulation ended up in the statute "in line with the colonial strategy of pandering to high-caste Hindus who played a key role in the rebellion".

The regulation from 1862 removed both the criminal penalties according to which sati is punishable as capital murder and others which mandate the death penalty in more serious cases.

This also meant that she enables the accused to claim that the victim herself agreed to end her own life at her husband's funeral, so that it is a case of suicide rather than murder.

Mita writes that the easing of sati regulations was a "reaction to simmering discontent with social laws"—the outlawing of sati, an 1850 law giving greater rights to outcaste and renegade Hindus to inherit family property, and an 1856 law allowing they remarry all the widows.

Watch the video: Woman or cow

Upper caste Hindu soldiers

But the immediate trigger for the emergency passage of the watered-down law was "dissatisfaction among upper-caste Hindu soldiers" who were enraged by allegations that bullet casings were smeared with cow fat.

From 1829 to 1862, the crime of sati was reduced from murder to assisting suicide.

"Although less practiced after 1829, sati continued to be respected and respected in some parts of India, especially among the upper castes," says Mita.

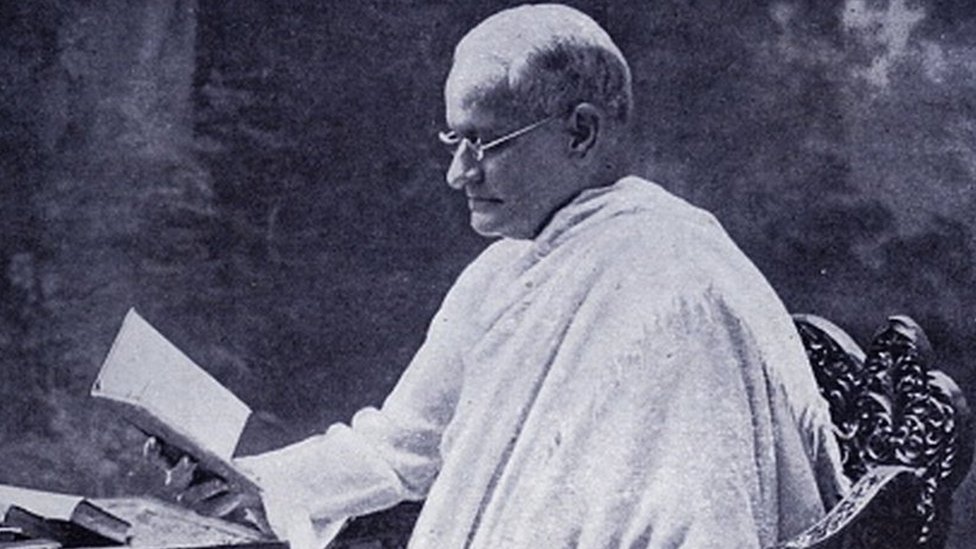

Motilal Nehru

In an unusual twist, Motilal Nehru, a lawyer-politician who entered the Indian National Congress and played a key role in the campaign for independence from British rule, appeared in court defending six upper-caste men in a 1913 sati case in Uttar Pradesh.

The men claimed that the pyre "ignited itself by the sheer force of the widow's piety."

Judges rejected the theory of divine intervention, condemned the attempted cover-up and found the men guilty of assisting suicide - two of them sentenced to four years in prison.

- "I'm looking for a man who doesn't fart and burp - signed: feminist"

- Why do women in India put period charts on their doors?

- "Who can love you more than yourself": Indian woman plans to marry herself

Rajiv Gandhi

More than 70 years later, there has been a final twist in the sati story.

In 1987, a government led by Motilal Nehru's great-grandson Rajiv Gandhi passed a law that criminalized the "glorification of this practice" for the first time.

People who supported, justified or propagated the hours could be sentenced to seven years in prison.

The law also declared the practice to be murder and reinstated the death penalty for those who engage in it.

The move follows widespread displeasure over the latest reported case of sati in India involving teenage bride Rup Kanwar in a village in the northern state of Rajasthan.

It was, Mita points out, the 41st officially recorded case since independence in 1947.

The preamble of Rajiv Gandhi's bill was borrowed from Bentinck's bill.

"It was giving mail, even if unintentionally, to a decolonized country to its former colonizer," Mita says.

Watch the video: "I felt my skin melting"

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter i Viber. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

Bonus video: