The apartment was climbed by wooden steps. Their crunching sounded to me like the words of a language spoken by a dead tree. I imagined what the stairs had to say:

I was born from an acorn on the slope of Majevica. I grew long, and dissolved the canopy before men in uniforms started winding their way through my forest. One leaned against me before falling. My crown froze in his eye. He died thinking the sky was made of leaves. I have a drop of his blood in me. Later that death also stopped. I was silent for a long time. Some mushroom picker would come up to me, some boy and girl would secretly love each other. When they came with axes, I couldn't defend myself. They cut me off from the ground, my veins are rotting there. They carved boards out of my heart. Take it easy, boy. All the knots, all the knots that are visible, are a record of the fact that I was once alive. Like you.

I didn't tell anyone about the monologue of the stairs. That was my secret. I began to carefully step on them, so as not to hurt them.

Smederevo

The first thing you see when you enter the apartment from the small porch upstairs is the wood stove. In the winter it was burning hot inside. The firewood had to be dry. Once the mother did not check the humidity, she just lit the quickly broken twigs with a match. They filled the room with smoke. From then on, she set aside the part of Politika, which her father read every day, for kindling. The second part of the newspaper, as always, was stacked next to the exit door, for the family members to take to the squat.

The paper would burn faster and if the wood was dry, soon the mischievous light yellow flames would play in the oven - the doors were not closed until the fire was burning. I would protest when my mother finally closed the door, I was delighted by the playfulness of the flames that seemed to twist and turn inside the oven, those naughty flame children. In their flaring up and then suddenly decreasing, straightening again, swaying, I saw a wild dance to the rhythm of my child's heart. Once I remembered that the logs, which my father used to bring from the shed in a bucket, were actually the sisters of the wooden basamaks. Maybe from the same forest. They will crackle and tell some wooden saga about the time before the axe, writing it out with flame for the last time. Too bad I never learned that language.

I would be lying if I said that I knew that the stove was from Smederevac. Now I think it must have been just like that. Stove with two doors - for wood and ash. Oven. And up there is eternally hot flesh. Sometimes I would be assigned to throw out the ashes, especially in winter, when there was a lot of it, because it was constantly burning. I would sprinkle the path to the squat, the wooden house next to the chicken coop. The ash would stick to the ice, some embers would fall into the snow with a loud sizzle for the last time.

The poker was one of my favorite items. "Give the fire a little," Mother would say. Admittedly, she would address her older sister, but I would be faster. I would open the heavy door with a rag hanging next to the stove, I would stare at the flames and embers. Then I would shake the burning logs and embers with the hook of the lighter. The fire would flare up. Over time, I learned to insert a log, if there is room. Then I would keep the door open longer, waiting for the flames to take the new wood as well. I would reluctantly cover the black frame in which the dramatic orange play of dying matter unfolded.

The pot and the trough

Sometimes twice a week he used to put a huge gray tin pot on the stove. White laundry, bed linen, T-shirts and underpants would be simmering in it. The oily and whitish water would eventually spill over the porch railing, in winter, in the thick snow, that water would carve out an entire landscape, exposing the earth that was sleeping under a blanket of white.

In fine, windy weather, the sheets spread out in the yard fluttered like white flags, in the summer they would stand still in the lee like sails on a raft in the middle of the ocean. Mother would spread the laundry in the yard even in winter. A whitish breath, foreboding frost, came rhythmically from her mouth. The bedding could stiffen overnight. When the mother would pick it up, stacking the wind-twisted and stiffened pieces on her hands like logs, those strange statues resisted the warm stove for a while in the apartment, only to eventually give way and smell of snow.

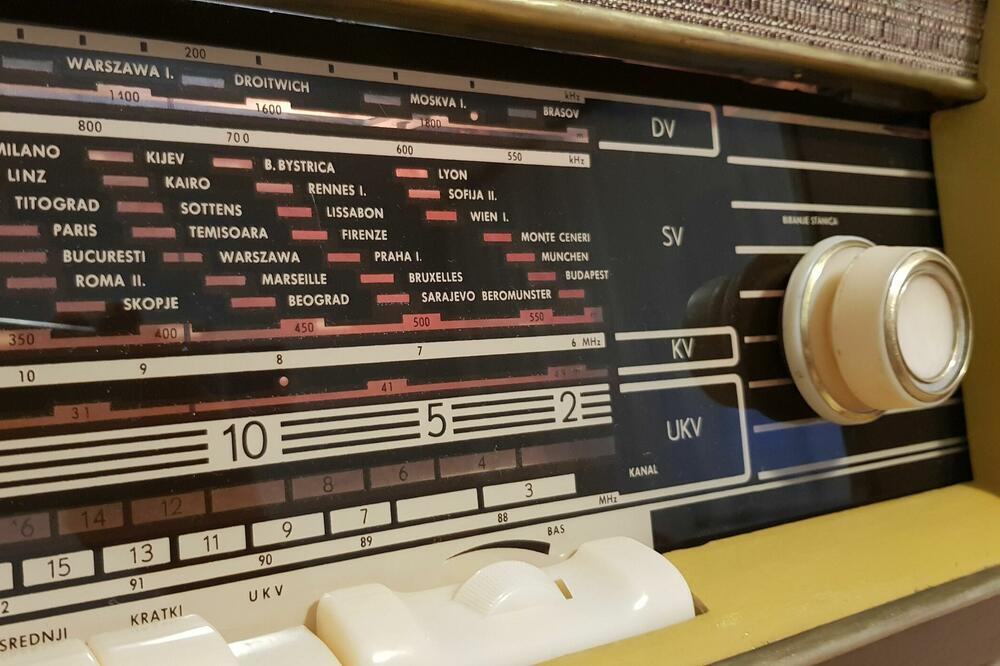

Made of the same material as the tin pot, there was also a trough, erected behind the sideboard. Once a week, the water in the pot was heated, and cold water was waiting in the buckets to mix with the spring. Mother first filled the trough halfway with hot water with a pot, placed in the middle of the wooden kitchen floor for the occasion. Then she added cold water, pot by pot. She would dip her finger now and then to check if her cubs could get in. Entering the water was a special ritual. You dip your toe, you complain that it's hot. Mother added cold water. When you enter, after five minutes you complain that it's cold. Mother added hot water, carefully, at the other end of the trough, so as not to scald you. I loved that feeling. Beside the pot of hot water from the pan, the rest of the lunch, kept on the stove, smells, in case someone gets hungry. The radio is chattering. Outside the world wrapped in snow wool. Icicles under the eaves. In the warm water, as in the womb, I feel that I am cared for and loved.

I don't remember the order in which the family members bathed, but it must have been a heroic effort, after the radio broadcast of the football matches, in the first winter twilight that covered the school yard, the stream behind it, the road and the forest that led to the mountain.

The light bulb glows, the light bulb shines

The light bulb, suspended from a cord on the ceiling, screwed into a black socket without a chandelier, was already protecting the room from darkness with its flickering warm, orange-yellow light. When I heard a word from my neighbor's son - his parents, like mine, came here to the village under the hill to teach, they from Osijek and mine from Srem light bulb, I thought that for this light bulb of ours that word is more appropriate. It glows more than it shines.

My father once unplugged another such light bulb. There were eggs in the straw carton. A hen lay there for a while, but one night her parents threw her out into the coop and turned on a light bulb above the cardboard box to warm the eggs. My mother called me, something was happening. The egg cracked from the inside. A beaked, slimy creature emerged from it. It rummaged through the straw. And then one more. And one more thing. I felt sorry for the chicks, lost in the world outside the perfect universe inside the shell. I didn't take my eyes off them. They were slowly learning to walk. The light bulb was drying them. They gathered beneath her. They looked more and more like yellow fluffy balls. Father took a chicken and carefully placed it in my palm. Although it was spherical, I felt such a fragile structure under the down that I was afraid to move, I might inadvertently hurt it. Then it leaked. I think I loved him right away.

Maybe half a year had passed, the chickens had grown, they were frolicking outside around the coop. I thought I recognized the one I held in my palm. White feathers and red crest. I was old enough to understand the connection between the chicken coop and the chicken dumpling soup I adored. But when father set his sights on my chickens once, I rebelled. As if by pardoning him, I will atone for all those spoonfuls of chicken that I mercilessly shoved into my mouth.

Pigeons

The father was soft on the children. He said we'll eat something else for a change. He brought a ladder from the shed and leaned it against the dark brown frame on the ceiling. He climbed up, lifted the wooden lid and called for me to pass him the sack. I took the coarse cloth, climbed carefully one or two rungs, father reached out and reached for the sack. He disappeared into the attic.

Under the roof, in the morning, pigeons cooed in chorus, you could hear the flapping of their wings. It was often the first sound that would reach my consciousness, which was slowly returning from the labyrinth of hilarious dreams. This time the flapping of wings was even louder, there was the anxious call of the birds and the father coming down the ladder, followed by a single feather that swirled all the way to the floor before the father could close the hatch on the attic.

Something moved in the bag. Father opened it and showed me the bodies of pigeons without heads. A few more jolts and everything calmed down. Severed heads were also in the bag, stunned eyes as if they were looking at the bodies that belonged to them until recently.

The mother washed the pigeons in a large pot in which she usually boils the laundry, gutted them, cleaned them. In one of them she found immature eggs. She put them in the oven too. Mutilated like this, the pigeons looked like stunted chickens. At that lunch, I got a tiny drumstick, and then another one. And the egg that will never become a pigeon.

Crabs

Father once caught rock crabs in the stream that flowed right behind the road. When he brought them home in that same pigeon bag, they were still alive. The father took one out on the wooden floor. Until then I had never seen such an ugly being. The hairpins looked dangerous, the eyelets menacing and malevolent, the antennae like Dali's mustache - repulsive. Father cooked crabs in the same pot for pigeons or laundry.

When it was time for lunch, the nurse caught a crayfish from the pot by the antenna sticking out over the edge and put it in my face. I ran to the other room followed by her laughter. I was convinced that the crabs were still alive and would grab my nose with their pincers. Needless to say, I was not allowed to touch them at the table. Father expertly tore off the clips, sucked up the white flesh, emptied several clips onto my plate. He used a wooden rolling pin to break the armor and take out the gray flesh, putting it next to the white. I tried it cautiously. It was even tastier than the birds.

A four-member family at the end of the world, under the majesty hills, ate what normally only the privileged taste. Now I know that lunch for four was indeed a privilege, which will soon be irretrievably lost.

The smell of milk, the taste of varenika

All that remains is to remember the bottle of milk that was waiting on the porch every morning. A peasant woman who could hardly move brought freshly milked milk, waddling along the basamaka early. They also told her their story with a squeak. The fresh milk smelled of grass, herbs, hay. His mother cooked it in a pot. I used to get all the cream - my sister hated it like crabs to me. When my mother managed to separate some of the cream and add salt to it, it was the most beautiful taste I can remember, together with pork fat and allspice on bread from the oven.

Milk was smoked from tin cups on the table. Its taste will irretrievably disappear in the coming era of pasteurization. During our Montenegrin summers in the fatherland, grandma used to warm up varenika for us. Varenika is the name for the love of the father's family towards his offspring.

And yes. In the bedroom, darkened by a green blind, a monster lived in the closet. It had a stocky body and a snake-like neck with ribbed scales. Sometimes I couldn't sleep expecting the monster to wake up. But it was a master of disguise - during the day it turned into "progress", an ordinary, bulky vacuum cleaner from the Sloboda factory in Cač. In the modest Yugoslav households of the XNUMXs, this kind of household appliance was an undoubted proof of progress.

Without these objects - wooden basamaks, Smederevac, a pot for boiling laundry, a tin trough for potting, heavy wooden radio-receivers with lamps in the guts, dirty vacuum cleaners; without an attic with pigeons and milk in a bottle at the door, I would be someone else.

Later in my life, the stove from Smederevo was functionally separated into an electric stove, mostly Gorenje, and a coal, wood, or oil-fired Kreka Veso stove (this addition to the name is the name of the German Weso foundry from the town of Gladenbach, which sold its license to the Banovićs in 1969). They replaced Sloboda's vacuum cleaner with an imported one. Gone are the squats, the troughs, the boiling of the laundry. That's called progress. In his course, a person gains a lot, but also loses something.

They say that a more reliable memory is preserved in the sense of smell than in other human ways of remembering. Sometimes on Sundays, I am half asleep with the smell of frozen laundry, fresh milk, hot varenika. In an instant, people and things that are no longer there come back to me.

Bonus video: