I haven't been in that part of town for a long time. But every time I come to Cologne, I want to see Jof. And he lives his life there, long since moved from Čačak and Belgrade. So, I take tram number five towards Ossendorf. Jof welcomes me at the door of his apartment. I'm sitting at his table, we're drinking coffee, and through the balcony window I can see the sun's rays gliding along the tram tracks. I remember our many years of companionship in Cologne, several of his addresses and several of mine. If neither of us notes something about those habitats, who will remember them - streets, entrances, building numbers. Names of neighbors, days, years.

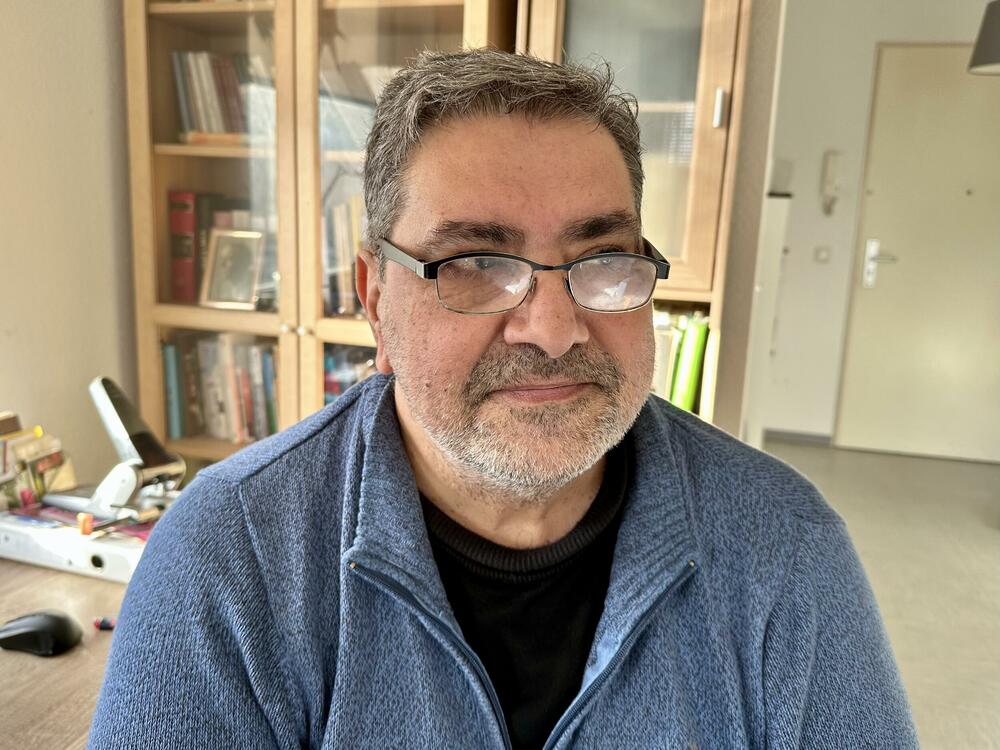

Jof is Jovan Nikolić in civil and literary life. He is a writer of the Serbian language and Romani musicality according to his father, a musician. He is preparing a new book for an Austrian publisher. We're talking about her. A series of smaller prose writings that revolve around the funny and sad side of love, blaring loudly about people without a homeland, about absurd human habits and dreams. So about all of us.

After several hours of chatting, I head for the exit. I wave to Jofa and instead of turning right, towards the Margaritastrase tram station, carried away by the soft light of the sun tilted to the west, I continue along the tracks straight towards the city. I decided to correct the injustice of one of the former addresses, which is ten minutes' walk from Jof's entrance. This is a record of her.

Belgian barracks Klerken

When I moved into an apartment bought on credit in the new Osendorfski Park neighborhood at the beginning of this millennium, I knew nothing about the history of that area. It turns out that she, although invisible, is more exciting than a neat neighborhood with geometric streets and neat facades.

In the 10th century, Ossendorf was a village that belonged to the noble family of Von Ossendorf. Since a vo is visible in the coat of arms of that family, it is assumed that the German word "okse" for this horned animal has been preserved in the name of the entire region. Ossendorf would therefore be translated as Volujska selo. It is recorded that the Ossendorf fields were planted with sugar beets as long as the sugar factory was operating - it shut down in 1909.

After World War I, the French occupied Cologne until the summer of 1930. As soon as their troops left the Rhineland, Berlin began building barracks. One of them is located in the center of Ossendorf. The nearby airport, which no longer exists, had to be protected by anti-aircraft defense units. Now I am amused by the fact that I was a member of the light anti-aircraft defense in Zagreb's Borongaj barracks, and the apartment that I could call my first property in Germany was located in the middle of a barracks originally built for units of the same kind.

After World War II, the barracks built by the Prussians turned out to be almost the only place where Belgian soldiers could be housed - most of Cologne was razed to the ground. Thus began the Belgian era in this region.

The Belgians will station their elite troops there. Half a century ago, there were up to 48.000 Belgian soldiers in Germany. The area of other city districts towards the center and the Rhine was demarcated from Ossendorf by a large semi-circular street with a symbolic name - Outer Channel Street. Behind that street was the barracks and a tangle of alleys around it. It should not be particularly emphasized that around the barracks bars with a Belgian taste have sprung up. Some of them were also visited by ladies who engaged in making soldiers happy for money. The whole area came out in disrepute. That is why the square meter of living space was unusually favorable.

My four walls

I came to Germany in 1992 - a few years after the fall of the Wall. It took some time for the Allies to sort themselves out, and then they began to withdraw their troops from the reunified Germany. Klerken Barracks was closed in 1995. The local business elite realized that the empty barracks was an opportunity for banks and construction entrepreneurs. The renovation of the barracks began in 1999. At that time, I lived with my wife and child a few stations away, towards the center, in a building with poor heating. I was definitely going to move. During one walk, we saw that the former barracks was being turned into a construction site. We crossed the invisible border towards Ossendorf and peered into the barracks. In one of the streets, they were erecting new buildings, while scaffolding was already on the old barracks. In front of the concrete skeleton of the new building, Mr. Heinrich, blond, close to fifty, with rosy cheeks, asked us if he could be of service to us.

It turns out that he is an intermediary in the sale of apartments, who works for a bank. And the bank loaned the construction. So she was able to lend to us as well, even though, apart from our work, we had no guarantees. In those days, sweet-talking Heinrich sold us an eighty-square-meter apartment the way a sack of cabbage is sold at the market, with some haggling and a hearty handshake at the end. Our financing was 110 percent. This meant that we borrowed ten percent above the value of the apartment. Parquet and furniture had to be bought. When we left his office, I realized that I had not become the happy owner of the apartment, but the living property of the bank.

Entering Clerken

Now, over twenty years after that fateful meeting, I enter the barracks. The gates and ramps, except for the main one, on the opposite side of the big circle, no longer exist. But I already recognize street names. August von Willich. German revolutionary who, after the defeat of the revolution in 1849, fled to London via Switzerland. During the revolution, his personal adjutant was a certain Friedrich Engels. In London, he became friends with Marx, and then parted ways with him forever. He's going to America. The civil war did not pass without him - he became a brigadier general of the volunteer army of the victorious North. Greetings, Augustus.

On the left side of the street are the old barracks buildings, beautifully renovated. If you are not sure what are new and what are historical buildings, just look at the trees. The tall one with strong trunks indicates that it was planted seventy years earlier compared to the rows of trees in front of the new buildings.

A trip back in time slows me down. I recognize the staircase where my seven-year-old son kissed a Turkish girl. Her older brother reported them to me. Right behind that building is King Baudouin Square. The Belgian king was on the throne for over four decades, until his death in 1993. Interestingly, a Belgian commission found in 2002 that Baudouin was at least privy to plans to assassinate Congo's first post-colonial prime minister, Patrice Lumumba.

Wonders of history. I was born in a city where one of the most famous dormitories was called Patrice Lumumba, and my child grew up in the playground of the square named after the king who beheaded an African statesman.

My street

I pass by the entrance to the doctor's office where I went to get prescriptions for a child with a fever, by the kiosk where I bought beer on Sundays because supermarkets are closed. Out of the corner of my eye, I can also see the beer garden of the Belgian bar, where I fell in love with Hogarden, a Belgian beer that is drunk from glass pots. Even that pub is gone. My street named after Peter Reser, a worker in the Cologne tobacco industry, labor activist and friend of Karl Marx from the time when the bearded philosopher in Cologne published the Rheinske Novine.

The building was yellow immediately after completion. It's a little darker now. This lady's face is aging fast, I thought.

I approach the entrance next to the number three and look at the surnames next to the bell. I read one by one. I know about half of the tenants. An old Turk who worked at Ford, his smart daughter and a son in a wheelchair. African pastor. A German pensioner who was still old then. Is he alive? For a moment I am afraid that I will find my own among all those names, that I will wake up like a sleepwalker in my former life.

I go around the building, look at the inner courtyards of the apartments and the small children's playground between them. I approach the hedge behind which is the garden with a terrace. Fortunately there is no one.

There I welcomed the sunset with a glass of wine and a book on my lap. Birthdays were celebrated there. The smell of barbecue. The murmur of former voices. For most of the people with whom I laugh casually in that memory, I no longer know where they are or if they are alive.

Departure

Leaving the barracks along Peter Rezer Street, I think about man's need to embellish the past. Nostalgia is a sweet term today. But at the beginning they saw a disorder in some ideal place in the pain towards the past. It was first mentioned by the Swiss doctor Johannes Hofer in Basel in 1688. "Dissertatio medica de Nostalgia", describes the sick longing for the homeland of Swiss soldiers. So, soldier's disease. In the former barracks.

I think I undertook this pilgrimage to the past to avoid sweetness. I was not happy living in the barracks. I did not like the neighborhood. Those were difficult, crisis years. And we tend to declare them beautiful in the rearview mirror, because they were the only ones we were given.

They built a new building near the Iltisstrase tram station. Cafe Kopenhagen is located on its ground floor. When Germans want to emphasize that something is "cool and fancy" they reach for Scandinavia. I go inside. Ossendorf can be seen through a huge window, as if from another dimension.

I'm learning coffee. Then the phone rings. Jof asks if I'm already on the tram, it's going to rain. I didn't. I'm in a time machine, I say. But it doesn't leak. Zekish?, Jof asks. I'll explain to you when I explain to myself, I answer.

Arriving at the new Cologne address in Kalka, I browse through my son's old photos. Among them I find one in which two decades ago the neighbor's children posed in front of my terrace in Ossendorf. Sicilian twins, always smiling. Turkish tough, he played football well. Faces of children who are now people. I wouldn't be able to recognize them on the street.

Many years ago I sold my apartment and went to another country. After some time, during one visit to Cologne, I went around the whole area. Then I felt the need to write down:

In the old neighborhood

The bakery from which I brought scones is now a schneider.

And a video library with children's films - a bakery.

Kindergarten demolished.

The garden of the Belgian pub became a warehouse for five shops. A large chain swallowed up a small supermarket.

Horst and Elvira divorced. We threw firecrackers in front of their haustor on New Year's Eve. He was talking drunk about a guy who wants to mate with a hamster.

We laughed for hours. Not even that laugh anymore.

The Turkish neighbor (white hair, tired) does not react, I must be different.

Here I felt life seeping through my fingers like lukewarm urine. Here I was a worried parent, a tired husband, a dreamy loan payer

about other places, another life.

So what do I regret? For a chance to leave the old part forever,

to forgive him before that.

Bonus video: