The night before the shooting of the scene with the monologue that was to be spoken by Roy, while dying in the rain, on the roof of the solitaire, Rutger Hauer, the Dutch actor, in the cult movie Blade Runner, wrote the decisive sentence: All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain... Time to die. (All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in the rain...Time to die)”. They say that the director Ridley Scott was surprised, and that the entire filming and acting crew started applauding, some of them even wiped away their own, real tears.

I knew back in the eighties, in the semi-darkness of the Sarajevo cinema, that this monologue is actually a melancholic instruction for life addressed to everyone who knows how to feel what their story is like. "I've seen things you people wouldn't believe...Burning spaceships on the shoulders of Orion...I've watched C-rays flash in the darkness at the Tannheuser Gate". Roy told me - before your life is lost like tears in the rain, you have to see places where you will think - if I wasn't here and I didn't see with my own eyes, I wouldn't believe it.

One of the heroes of film fiction, a sci-fi being stuck in an aesthetic between film noir and cyberpunk, advised me to become a Traveler. Albert Einstein once noted that there are only two ways of looking at the world: "Either you believe that nothing in the world is a miracle, or that there is nothing but miracles." The film, which I absorbed with all my young being, showed me in time that I belong to this second type, that I believe that a wonderful world should be discovered.

I have always been aware that many others before me have been in all the places I aspire to. When I am struck by the vibrancy of a place, I try to make out through the noise of today the small voice of former travelers. Wherever they have been, they always have something to tell me. Sometimes I can hear them. Sometimes the noise of the world is louder.

Those who blazed the trail

One of the first in history to bequeath his name as a traveler and write about what he saw is Skilak. The confluence of the Indus with the Arabian Gulf, perhaps even the confluence of the Ganges with the Bay of Bengal was the starting point of his travelogue. How he got there as a Greek is anyone's guess. Some say that he was a navigator, others see him as a ship captain who, by order of the Persian emperor Darius the Great, maps future military campaigns. From that point Skilak moves around the Arabian Peninsula, and further, through the Red Sea all the way to Suez. He summarized this in a book on coastal navigation, which in Greek was called periplus, from which other languages later made periplo or peripl. It is not very reliable, but it is assumed that he made his records before the imperial campaign against the Scythians in 514 BC. There are also records about the Mediterranean attributed to him, but the author is someone else, unknown to us. The latter is actually a compiler, nicknamed Pseudo-Scylacus, because the notes entitled "Description of the Sea Coast of the Inhabited Areas of Europe, Asia and Africa" were created almost two centuries after Scylacus.

On his travels in the 4th century BC, Pythias of Marseilles seems to have visited the British Isles and unknown destinations in Scandinavia where "the sun never rises".

The ancient Greeks, therefore, traveled east and west and north in times when it was painful and often life-threatening - and wrote about it. Herodotus also recorded his travels.

How did a Russian drink 1100 years ago?

Surprisingly, among the ancient Roman chroniclers, we do not have prominent travel writers. But Jews and Arabs regularly report from their travels. If it wasn't for Ahmed Ibn Faldan's diplomatic mission in the 9th century - the Abyssinian Caliphate sends him to Prabugar on the Volga - we wouldn't know how colorful and gruesome the ritual burial was among the people he called Rus. "The Slavs first put a roof over the bier of the deceased, which stood over it until the suit for the deceased was sewn. The deceased is placed in a boat; if he is rich, they divide his property into three parts: one part belongs to the family, with the second they buy a funeral suit for the deceased, and with the third part they buy drinks for this celebration. In these incidents, they get drunk to the point of unconsciousness, and some of them die from drinking at these festivities." It seems that the saying "drinks like a Russian" is older than we think. The diplomat and travel writer did not have a good opinion of the Varangians, as the Slavs, and later the others, called the Viking warrior-trader brotherhoods. He described the orgy of that male gang with young Slavic slaves. He also described the harem of the Khazar ruler and many other miracles of that time.

The Jewish intellect left us a gift in the travelogue of Benjamin of Tutera - that is the Basque name for the town of Tudela in the former Kingdom of Navarre. In the 12th century, he reached the Orient all the way to Basra, stayed alive, managed to return and write everything down.

From Venice to Beijing

Crusaders and pilgrims to Jerusalem and Mecca and papal envoys Genghis Khan wrote about what they saw or what they thought. There was always some religion, some money or some sword that covered the way for the travelers. Sometimes and all at once.

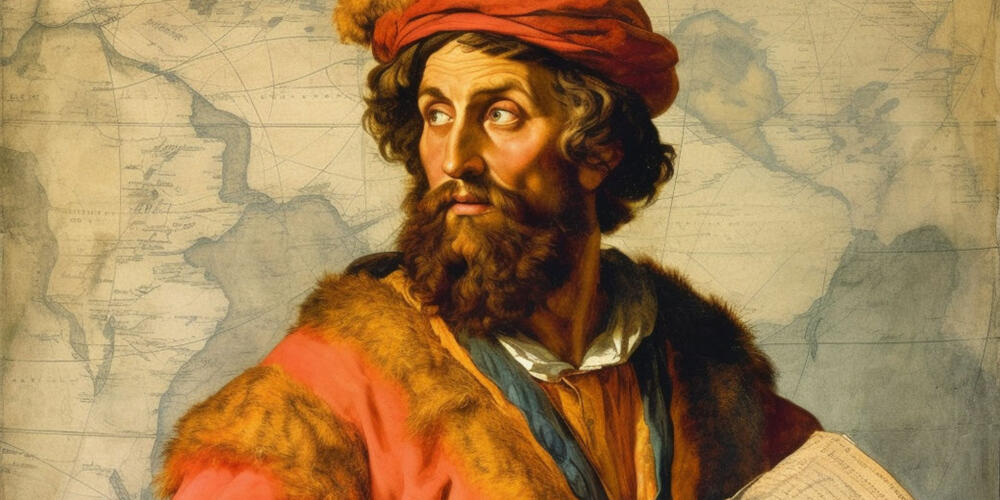

Marco Polo dictates his stories of Far Eastern travels to Rustichello da Pisa. If it hadn't been for the Genoese-Venetian war and the prison he liked, there wouldn't have been a book The million, we would not have seen the Silk Road through his eyes.

Although Marco Polo is part of the common European heritage, we should also remember the Moroccan Ibn Battuta. He covered 117 kilometers in three decades, along the entire Islamic world, China and India. Several times his ships sank in storms, he was robbed, but also appointed to important positions in several countries, he passed through cities destroyed by the plague, he saw more than all his compatriots put together. When he returned to his homeland, the Moroccan sultan persuaded him to dictate his travels to the learned scribe Ibn Juzai from Andalusian Granada. The manuscript had an ornate title: A gift for those who fantasize about the wonders of cities and the wonders of travel. "Rihla", which means "journeys" in Arabic, remained the usual name for this book. The world traveler Ibn Battuta bequeathed us a beautiful thought: "Travel - first it leaves you speechless, and then it turns you into a storyteller".

Finally, in Morocco, the plague reached him. I'm convinced that's what happened because he stopped moving.

Colonies, empires, crimes, marketing

The discovery of America, the arduous creation of the new and the terrible disappearance of the indigenous world are shown to us first through the eyes of Christian missionaries with a pen. The eyes of the missionaries did not leave a deeper mark on that literature. She was also a travelogue in a way.

The colonized peoples had no voice, they were the object of observation, sometimes haughty misunderstanding, even benevolent admiration, but essentially they would remain a frozen, never living subjectivity. In postcolonial discourse, the turkey is turned upside down, prejudices are forced out of the cave of the subconscious and shown to their astonished owners. But those who justified their conquests with the need to establish local civilizational standards could not recognize in their own way of thinking anything but good intentions. When the colonial empires collapsed, that good intention retreated into resentment at the ungrateful savagery of the awakened peoples. And then it crept up again at the bottom of the subconscious of the former empires as cultural racism. All this spilled over into the digital mess of this millennium.

We haven't solved any of the fundamental problems of the last century, but we communicate and travel more easily than ever. We turn everything into folklore about ourselves, so we don't draw the attention of tourists that there is a better party here than at the neighbor's. In the time of the dream of emancipation, we struggled to refute prejudices about ourselves and our history. Now we amplify them to the point of caricature, pack them in convenient packaging with English inscriptions, now we act like fools when someone casually says that it is lucrative to be a fool. And so we become fools.

This is the basic problem in travel - how to recognize authenticity, how to distinguish it from staged chewing gum for naive tourists? The face of the world, suffering and beautiful, full of scars and charisma, is slowly disappearing behind the marketing coating. Ethno-staged and anesthetized places that hide their scars are not perfect but hypocritical.

Happy prejudices

The French Enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu once visited neighboring Germany. The Germans made a good impression on him - they are reserved at first, but then they are really good. Nevertheless, the Frenchman described it in his own way, comparing the Germans and elephants: "At first glance, they look rough and wild." But as soon as you caress them and flatter them a little, they become gentle. Then all you have to do is put your hand on the trunk and they'll happily let a man climb on their back." This is funny, but it's also mean in a way.

In his German travelogue, Mark Twain was horrified by the German language and delighted by Heidelberg.

Goethe traveled through Italy to find the image of ancient harmony, Heine was already enough four-week trip through the hills of the German Harz to write his best travel book. Elias Canetti heard voices in Marrakesh, Heinrich Bell kept a diary in Ireland. With his records from the Soviet Union, Andre Žid caused an identity crisis of the intellectual left in the west of the European continent.

In this travelogue, I deliberately stay away from famous travel writers who - like Evlija Celebija - wrote about us. Or from what our and foreign travel writers bequeathed to us visiting the "region". I don't want to have to chase the elephants out of the text later. But I had to make one exception.

Zuko Dzumhur

Džumhur's text "Journey through nonsense" from the book "Obituary to a bazaar" shows me that traveling can also be a hammer for breaking precious illusions. Zuko first describes how, as a child, he looked at a picture of an oasis in the mirror of a Sarajevo barber shop. "For a long time, my eyes were full of colors from the lithographed colorful lies. In the middle was a well. There were three or four palm trees in the picture. The Sheikh was sitting on soft mattresses. The sheik was as handsome as Ramon Novaro. Fragrant flowers were blooming all around. A white Arabian horse was playing by the well. His reins were golden. An unclothed woman was banging on the door. The other unclothed women were eating dates. One unclothed woman was blond and sat indecently. The picture was night. The moon was as yellow as a muffin.

After many years, a colorful illusion from a lithograph in the mirror of a Sarajevo barbershop has disappeared.

An oasis is a cemetery of petrol barrels.

The gray, dusty leaves of some desert grass cover the stone opening of the well. Sheik was not there. There were no undressed women either. Nowhere does a man think so intensely of an unclothed woman as in the desert. There wasn't even a white Arabian horse with golden bridles. There were only three or four palm trees. Tattered and ugly, they stuck out in the vault like huge burnt brooms used to clean hell. An Arab soldier defecated behind the wreckage of an abandoned car.

There was no moon.

Zuko lost his oasis from his Sarajevo childhood in a real desert. I wonder, would we be ready to bear this much truth that some traveler would write about us and our daily deserts? This brings me to the question of how real travel prose is.

In a way, the countries from the travelogue, even if they were completely real, become fictitious through the operation of transferring them into the text. Not in the manner of Jules Verne and Karl May. But more like Handke's Serbia. Nothing written in Handke's travelogue is a mistake of fact. But the intentional polemic with the Western narrative - which also does not have enough facts, but too often operates with simplifications, repetition of platitudes from the nineties and ignorance of details - as well as the unspoken things about the country itself, turn that prose into a phantasmagoria. Serbs generally did not read it. But its existence is enough for them to annoy some people in the West. This is already proof that the travel writer is - if not exactly Russian, then at least an Austrian Serb.

The traveler and the roads

I listened to Roy. I've been traveling all my life. First, from early childhood, through labyrinths of books. By reading, I got to so many places, in so many eras, that before my first serious trip I was already an experienced traveler. Odysseus made of paper. When I got the chance to actually travel, there was no stopping.

I've seen things beyond belief. A drop of rain hesitates for a long time until it breaks off the tip of the nose of the bronze hamal in Istanbul. And in the drop, as in a glass ball, the first ray of the sun after the rain and the whole of Constantinople are caught. I watched the dervishes boring the passage to the heavens like squires. The sun-kissed Težo rolls sluggishly towards the Atlantic, and in the city alley on the ridge an old man tunes his guitar for fado. In Palermo, the street stone shines, polished by the soles of generations. It also shines in Split. A Roma plays Christmas carols in the Balkan key in front of a textile store in Cologne. Roasted pumpkin is smoked at Sulejmanija. And grilled fish at the Izmir market. Nuremberg sausages are also smoked near Dürer's house in Nuremberg. A cemetery in Thessaloniki with cypress trees from Hilandar. And a cemetery in Berlin with a stone that says Heiner Müller. Blagaj tekkia under the stone wall, above the wonderfully green water. Beer foaming in the former Prague monastery. Sparkling anise in a bottle of ouza on Zakynthos. I am seduced by the floral aromas of Riesling in a sparkling wine glass, at a small table on the river bank in Trier.

Cretan red earth. Banat Black Forest near Vršac. And Bačka černica around Sombor. A meadow descends like a slide to curve towards Komovi.

It seems to me that I write it down so that all these moments do not disappear in time like tears in the rain. Travel is the best narcotic. "The experience that we are capable of pure enthusiasm is a real gain on the journey," wrote Goethe. Yes, encountering a new landscape, street, water brings a rare kind of joy. First of all, we are dumbfounded by it. So turn us into storytellers. My favorite fantasy writer, Ray Bradbury, noted, “Travel out into the world. He is more fantastic than any dream”.

Bonus video: