Winter in Sarajevo could start as early as November and last until March. The city would then be littered with garbage. Utilities would not be able to deal with the white, cold substance. But on the eve of the Winter Olympics, socialist citizens were able to take to the streets with shovels at the invitation of the city authorities. They were everywhere, shouting to each other across the street, in the city dialect that in those years would be branded by a group of sprightly people gathered around the name Top list of surrealists.

The neo-primitive movement was just beginning, the Olympic year would bring its breakthrough in Yugoslavia - garage rock and punk and lyrics with violent characters who listen to folk songs, come down from their slums to beat hippies and despise the West.

Everyone in Yugoslavia liked it. Not to me, a long-haired student. Stylized marginals from neo-primitive aesthetics were not invented. The streets of Sarajevo were full of them. Uneducated, brutal, colored by mahal slang, they knew how to "shoe" someone who seemed different to them for no reason. Having watched these street guys in action, narrowly escaping such treatment several times, I did not accept their new status as subcultural heroes, even in an ironic key. The "Movement" breathed local patriotic meaning into the senseless petty-bourgeois thug, made his violent-illiterate matrix the foundation of a new urban mythology. What that half-world is really ready to do was shown at the beginning of the war in Sarajevo, when the neo-primitive heroes started wielding real weapons.

Happy New Year 1984.

I entered 1984 without a single thought about the upcoming Olympics. My fellow poet and college friend Majo and I met the train to Belgrade on the eve of the holiday. It was a time when the trains stopped at the platform for a long time, and then sighed, as if a great burden was falling from their iron heart. Two female students from Belgrade got off the train. I found the slender one, with black silky hair and eyes the color of Riesling grapes, in Makarska the previous summer. Since then, I often went to her in Studenjak in Belgrade. She came to Sarajevo for the first time for the New Year holidays. She took her roommate with her, to whom Majo will be attached for the next few days. The roommate won't mind. Our friend Butko, with whom we hung out in the faculty poetry club Tin, invited us to his parents' new apartment near the Airport. The old people have left, and a dozen of us, mostly students, will fill the apartment that New Year's Eve. The girls slept the night before in the Željezničar Hotel because the Sarajevo landlady rented us rooms with a strict ban on female visits.

Sarajevo patriotism

In a way, the Olympics brought confirmation to the people of Sarajevo that they are important to Yugoslavia and the world. Taxi drivers learned a few words of English, in order to explain this or that to the foreigners, of whom there were more and more. When softened by the Sarajevo palate, that language sounds hilarious.

They watched the fleet with envy Mitsubishi, a gift from the concern to the city. The Japanese vehicles looked like a science fiction artifact among the fiches, stands and Skodas pressed in with snow. Only the Sarajevo shanters who operated in the West knew how to park western-made sports cars in front of some of the cafes. Everyone who wanted to show themselves and the bazaar that they were somebody and something drank stok and smoked Sarajevo marlboro.

One such character was waiting for foreigners in Skenderija in front of the commission - that is, a shop where foreign goods were sold in a limited volume - and begged them to buy him a few Japanese watches. He would then "roll" the goods on the streets of Sarajevo for a good profit. Lipa, then a sports reporter, told me that in front of the Skenderija commission, a character intercepted a Japanese man and explained to him what he wanted. And the Japanese rejected him in a harsh tone, saying that he should be ashamed, because he is harming his country. The Japanese feeling for the common good and honor collided with the petty-minded mentality of Sarajevo's streets. Trying to calm the Japanese guy down, the guy kept repeating, "You fool!"

Lipa also told me that in 1984, his little boy ran up in a panic and pointed with wide eyes at a group of Americans on a Sarajevo street: "Black man! Black man!” The boy saw a black man for the first time. Thus, Sarajevo began to take in a distant and strange world, to get used to it. And the world was getting used to Sarajevo - the socialist, non-aligned Orient in the middle of the Bosnian hills.

We were not from that story

We were not part of that story. We listened to rock and jazz, read a lot, went to concerts, ate on student vouchers and drank Sarajevo beer in cheap bistros. In the period leading up to the Winter Olympic Games, there were frequent concerts of world-class performers. In October 1982 it was one of the best live gigs I've ever attended: an English rock band Wishbone ash she set the highest standards in Skenderija, it was difficult to surpass them. In January 1983, the new ice hall Zetra became the stage of the most bizarre concert I ever attended. Alvin Lee, the guitarist who, in 1969, at the age of twenty-five, played this way at Woodstock I'm Going Home that he received the unofficial title of the fastest rock and roll guitarist, he came to Sarajevo as a forty-year-old. When he went on stage, hockey players were still training on the ice in Zetra. The lights didn't go out. Between the audience in the stands and the fast-fingered guitarist, there was a forbidden zone of the glittering Sarajevo ice. At one point, disgruntled fans jumped over the fence and ran towards the stage. The people's militia did not like that. There was sliding, falling and clubbing with superb sound I'm Going Home.

There is a band in May Uriah Heep played his, pampered and overjoyed, leaving the stage in Skenderija after less than an hour. In June, the convalescent Peter Green played solidly what he had to at the same place, but in a small hall.

Counting down the months and days until the Olympics, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the toughest version of Yugoslav socialism, showed the world its chocolate face. We twenty-somethings enjoyed that simulacrum of freedom. The city where the first coffee shop in Yugoslavia was opened now had hundreds of them. Some worked all night.

The city in a girl's eyes

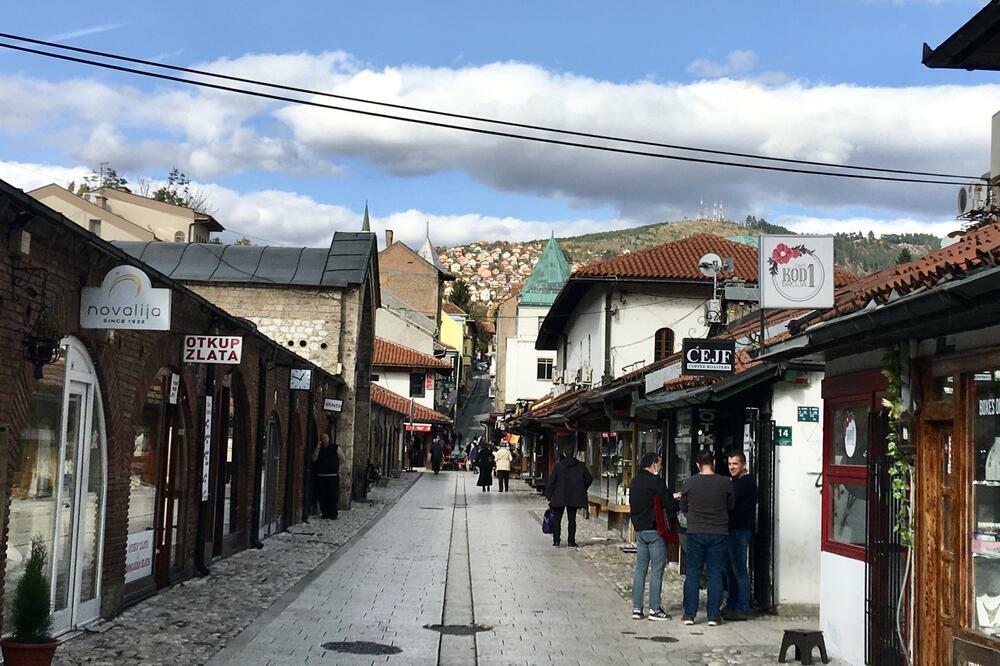

Forty years ago, athletes from distant parts of the planet came to this and that Sarajevo, accompanied by a mass influx of journalists and tourists. When the girls from Belgrade came to us, we turned into proud city guides. Vase Miskina Street - Sarajevo's corso - glittered washed and made up. Pastry shop Egypt hinted at the oriental sweetness of the city with the taste of tufahia, which would attack all the senses only when one stepped from the Austro-Hungarian to the Ottoman part of the city. Baščaršija with warehouses and a colorful maze - a labyrinth that smells of barbecue and ground coffee. The most famous place next to Miljacka was the one from which Gavrilo Princip shot in 1914. Opposite the bridge that then bore Princip's name, groups of tourists gathered around the guide to listen to a short history of Young Bosnia in the languages of the world.

Girls from Belgrade quickly fell under the influence of the famous Sarajevo charm. Kemino, Čolino and Bregino Sarajevo looked for and found scenes from the film "Do you remember Dolly Bell". They weren't interested in the places we used to go out - Sloga, Zvono, Korzo, Lovac, Pozorišna, Klub knjiženika. We had to Holiday Inn. Opened in October 1983, it was the first hotel of its type in Yugoslavia. The building looked like it was made of giant yellow legos. Everything was oversized - a huge hall, a reception desk, a cafe with fancy chairs. With my mane in a colorful sweater, I felt like I didn't belong there. In Sarajevo they would say that I felt like a stern in Tehran. It is important that the greenish eyes of the girl above the cup of coffee shone - she peeked into the world that is normally seen only in American films. The official ideology of egalitarianism was here completely suspended by the exaggerated politeness of the liveried waiter, behind which was actually hidden a well-toned irony. He quickly realized that the student population sat down to drink there out of curiosity. But he served us theatrically.

Waiting for Butko's apartment to become available, the next day we took the tram towards Ilidža. We left at the student dormitories in Nedžarići. We walked to the airport. Ordered mulled wine in the airport cafe. I tried that drink for the first time in my life, it also reached places with an international sign, replacing my dear, banal, boiled brandy. When Butko appeared with a wide smile, we were thinking whether we should drink the third mulled wine. Suffice it to say about that New Year's celebration that my girlfriend will state after a few decades that it was one of the happiest New Year's celebrations in her life. That's when she fell in love with Bosnian warmth.

The Trebevic story

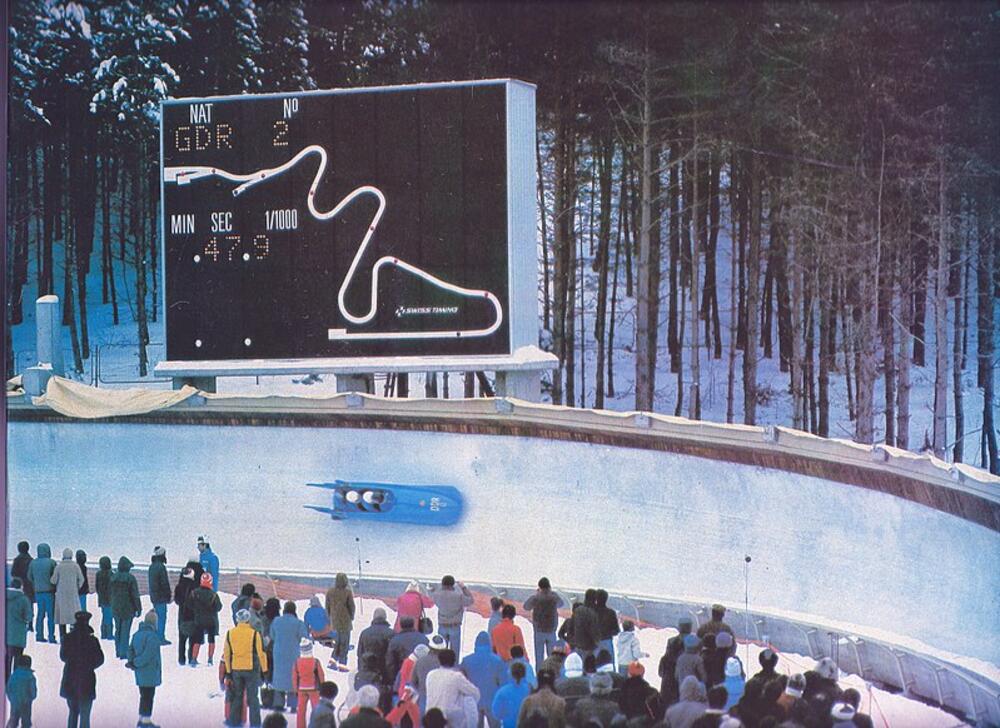

We had to show the girls from Belgrade something of the real Olympic arenas. The choice fell on Trebević. Converted military trucks with benches transported tourists to the new bobsleigh track. We climbed one of them and after half an hour descended into the snow kingdom. Below us, the city looked like a sugar-coated honeycomb with white caps and black snakes of smoke curling from the chimneys on the mahal slopes. The bobsleigh track was impressive. Much later, I found out what the mayor of Sarajevo, Anto Sučić, answered in Athens in 1978 when asked by the president of the International Olympic Committee whether Sarajevo guarantees snow. Sučić referred to weather reports in the last hundred years, which testify to the abundance of snow. He added that Sarajevo would guarantee optimal conditions for athletes. He pointed out: "Nevertheless, falling snow is not within my jurisdiction as mayor." One could say that the witty answer was completely Bosnian. Matters that were outside the mayor's jurisdiction were now all around us in Trebević.

A man in ski gear was selling tickets for the sleds, which looked more like a large rubber trough. I never dreamed that I would be able to go down part of the bobsleigh track. The girl's hair fluttered like a flag, obscuring my view. We were sitting close to each other, the sled was leaning dangerously on the bends, the shadows of the pines were moving around on the white background. We screamed with fear and joy. Then it all stopped. Dazed from the drive, with weak knees, we headed back into town.

Olympics on screen

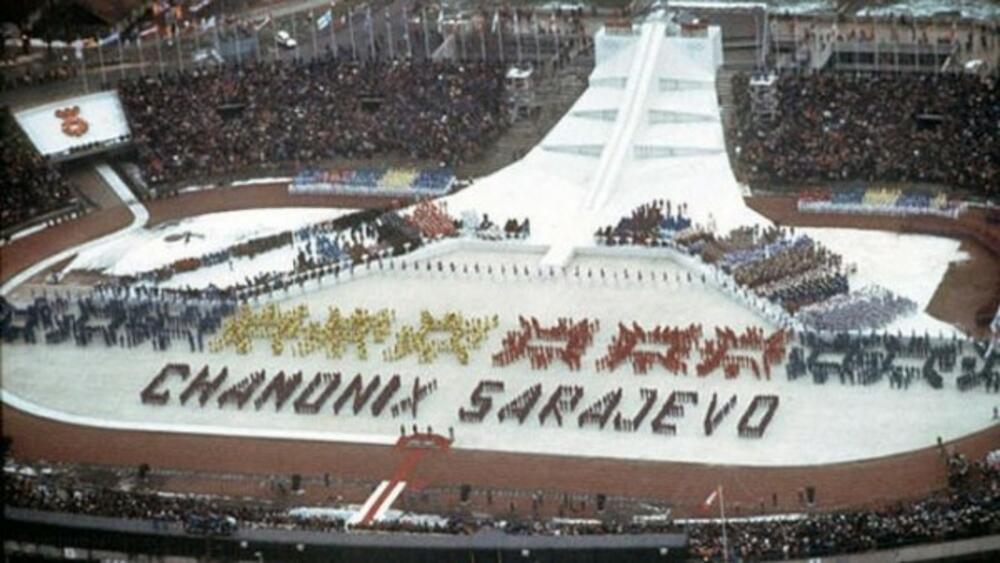

That was my Olympic Sarajevo. I watched the opening of the games at home, in Kalesija. On Koševo, the figure skater from Zagreb, Sanda Dubravčić, lit the Olympic flame, and the then president of the Yugoslav Presidency, sixty-eight-year-old partisan Mika Špiljak, said: "I declare that the 14th Winter Olympic Games in Sarajevo are open!" Television memories include two more moments. Jane Torvill and Christopher Dean dance to Ravel's Bolero on the same ice where the people's militia beat up Alvin Lee's fans. The moment when sport became pure poetry. And the silver medal that skier Jure Franko wears around his neck in Skenderija - the sports officials promised him as a reward Hitachi video player.

My life will once again intersect with the Olympics, right after it. In Sarajevo, I learned that the Americans were looking for extras for a film about their Olympic downhill champion, Bill Johnson. It will be the only film in which my student face from Sarajevo may be involved - we extras enthusiastically cheer on the skier who is followed by fast cameras. I can't be sure, but I think it's the movie "Going for the Gold: The Bill Johnson Story." I never looked at it. I remember that I spent the whole day on the mountain, and that they distributed the fee to us in cash.

And that would be it. Today, when I see Vuček being sold in Baščaršija, together with ballpoint pens made from shell casings from the time of the siege, I smile as if I saw a living peer about whom stories were spread that he did not survive the war.

And that girl who came to Sarajevo from Belgrade to celebrate in 1984, to fall in love with him, I now see as my personal Olympic medal.

Bonus video: