A traveler who comes to Rome and stays there for a few days, sooner or later will come across an area on the left bank of the Tiber that is unusual in that it is actually the only square in the city where no church has been built. The fluffy name Field of Flowers - Campo de' Fiori - should not mislead. The square was a place of loss and torture.

Now tourists can buy expensive souvenirs, fruits and vegetables at market stalls. It is actually a staged market for foreigners with deeper pockets. A charming Italian scam. The historical essence of the place is located on the pedestal. Human figure with a hood. It represents Giordano Bruno, a former monk of the Dominican order, a man who crossed Europe trying to live and think freely, only to be condemned as a heretic by the Roman spiritual authorities, and burned alive at the stake in this idyllic place on February 17, 1600. .

Monument to Giordano Bruno

Before we dedicate ourselves to the memory of this unusual and bold man, with a sharp mind and tongue, we should tell the story of the monument erected to him in 1889. The Grand Orient of Italy, the first large Masonic lodge on Italian soil, was founded in 1805. Among the Grand Masters even Garibaldi was a member of that Masonic lodge. Its prominent member in the second half of the 19th century was Ettore Ferrari. He was elected as a member of the Italian Parliament in three terms, but he was also known as a sculptor. He did not like the fact that in April 1884, behind the walls of the Vatican, not even a twenty-minute walk from the Field of Flowers, Pope Leo XIII announced His encyclical "Humanum genus" accused the Freemasons of wanting to destroy the church. It was nothing new. Since 1732, as many as 17 encyclicals directed against the Freemasons have been published. But the reaction was new. Ettore Ferrari was skillful and powerful enough, and he managed to remove the fountain in the Field of Flowers and raise the granite plinth. He carved the figure of Giordano Bruno himself, facing the Vatican. The monument is dedicated to all free-thinking people. Secular Italy saw a hero in a man who defied church dogmas and the Inquisition, and because of that he was turned into a living flame. Ettore Ferrari was the Grand Master of the Grand Orient Lodge of Italy from 1904 to 1917. But his most striking legacy in the city is the monument to Giordano Bruno.

There are reliefs on the pedestal - a gallery of denounced and burned defiants. The Venetian Paolo Sarpi survived three assassinations - the orderer was the then Pope. Tommaso Campanella served 27 years for his writings and views. Pierre de la Rame, a French philosopher and humanist, was killed in Paris, in the massacre of Protestants on Bartholomew's Night, and thrown into the Seine. Lucilio Vanini, a Roman philosopher whose tongue was torn out alive as a heretic and burned at the stake - he was thirty-three years old when he died in agony. Aonio Paleario, a humanist who advocated church reform, was first hanged and then burned. Miguel Serveto, a Spanish humanist, condemned in Catholic France, fled to Calvinist Geneva, where the city authorities - also for heresy - sentenced him to death and burned him at the stake. The English reformer John Wycliffe, responsible for the first translation of the Bible into English, the forerunner of English Protestantism and the Hussite movement, was more fortunate. He was posthumously declared a heretic by the council in Konstanz in 1415, ordering that all his books and bones be burned. His follower, the Czech reformer Jan Hus, was burned at the stake in Konstanz in the same year by the decision of the same assembly.

A comic about madness

During my stay in Rome, I experienced that monument as a reminder. Nowhere is European dogmatic madness more vividly described than in that place. The reliefs at the foot of the monument to Giordano Bruno are a kind of comic book about the strange religious customs of a civilization. Our age tends to simplify things. Art historians talk enthusiastically about the revolutionary aesthetic achievements of Renaissance Italy. Tourists drinking cappuccino watching the dark silhouette of Giordano Bruno, may have been in the Sistine Chapel on the same morning. They admired Michelangelo's frescoes on the ceiling. Michelangelo started working on them exactly 40 years before the birth of Giordano Bruno near Naples. And he finished work on the 520 square meter ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, four years later. Of Michelangelo's 115 characters, the most famous are the two characters from the "Creation of Adam" scene. Whitebeard God and Adam. So, little Giordano was born in a world where there were already Michelangelo's frescoes, his sculptures like David, his dome on St. Peter's Church. Nevertheless, the unusual beauty of Michelangelo's works, the splendor of Italian cities, could not inspire the ecclesiastical and secular authorities to refrain from burning people alive. And just half an hour's easy walk from the Sistine Chapel. What kind of world is it in which it is possible for Michelangelo's frescoes and pyres for heretics to exist at the same time? A world where inspired beauty doesn't protect against horror? It is the Renaissance world that we are inheriting.

The boy from Nola

In the family of Giovanni Bruno and his wife Fraulisa, in January 1548, a boy, Filippo, was born. The family lives in the small town of Nola, about thirty kilometers northeast of Naples. The boy will later call himself Nolanac. It is recorded that he began studying in Naples at the age of 14. Three years later, he joined the Dominican order. When he became a monk, he got a new name - Filippo became Jordanus. The Italian version of the name is Giordano. Not even a year has passed and Giordano Bruno comes into conflict with the leaders of the order because he did not recognize the cult of Mary, and he threw out all the pictures of saints from his cell. They forgave him, considering it an adolescent delusion. In 1572 he became a priest. He studied philosophy and theology.

His views first aroused genuine doubt in 1576. It was rumored that he was skeptical of the Incarnation - the teaching that God became flesh. He had to flee from Naples to Rome, intending to seek forgiveness from the Pope. When word got out in Rome that he had thrown the writings of St. Jerome of Stridon into the toilet during his escape from Naples - he had to flee from Rome as well. He leaves the monastic order, moves from city to city - Savona, Turin, Venice, Milan. Copernicus's ideas and philosophy of nature increasingly influence him.

Heretic, philosopher, polemicist

He leaves Italy and joins the Calvinist church in Geneva. Soon, he publicly opposes a prominent Calvinist professor, and ends up in prison. He renounces his views to get out of prison and goes to Toulouse. There he becomes a professor at the university, lectures on Aristotle. He develops a memory technique that fascinates his contemporaries and gets him into trouble because they think he's practicing magic. Conflicts between Huguenots and Catholics are increasingly open and Giordano finds refuge in Paris, where he is supported by King Henri III. He recommends it to his ambassador in London. So Giordano Bruno went to the city on the Thames. There he publishes Italian dialogues in which he caricatures the spiritual climate he found, but also his work About the infinity of the universe. It advocates the idea that stars are actually suns and that there are countless worlds in which there are intelligent beings. After two years, he returns to Paris. He causes a scandal with his own 120 theses against Aristotle, and when he publishes a mocking document against a famous Italian mathematician, he has to leave the city. The next stop is Germany. In Wittenberg he received permission to teach philosophy at the university. He publishes two books. Soon a quarrel breaks out between two groups of theologians and Giordano goes from town to town again - Prague, Tübingen, Helmstedt, where he gets a professorship. He prepares the Frankfurt writings, but does not finish them, because the Lutheran church also excommunicates him.

Obviously, a pattern was repeated in the life of Đordan Bruno - with his great intelligence and well-readness, he gained the favor of worldly rulers, and then he made enemies out of local theologians, mercilessly arguing and mocking. He was sharp-witted and of an awkward character. His irreconcilable criticism of Aristotle and his rejection of Jesus as the Son of God brought trouble and persecution. At the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1590, Giordano Bruno met a distinguished patrician from Venice, Giovan Zuane Moćeni, who invited him to come to the Republic of Venice.

Italy again

Nostalgia is dangerous for a man who had to flee from several European cities. The call of the homeland was the call of death for Giordano Bruno. But he couldn't know that. In his time, papal authority did not extend to the possessions of Venice. The Venetian aristocracy was not inclined to obey the papal will. Giordano thinks about the invitation sent to him by Mocenigo.

First, he decides to accept an invitation from Padua, which was then under Venetian rule. However, Galileo Galilei pushed him out of that city with his powerful connections, taking away his chair. Galileo would later write that his 18 years in Padua - with a good professorial income - were the happiest period of his life. His luck pushed Giordano Bruno into the ultimate disaster.

Giordano had nowhere to go - he accepted the invitation from Venice. It turns out that the host didn't want his learning but the secret skills of alchemy and black magic. When he didn't get that, he decided to get rid of the guest. He reported him as a heretic. The Venetians imprisoned Giordano Bruno until they decide whether to hand him over to the papal inquisitors.

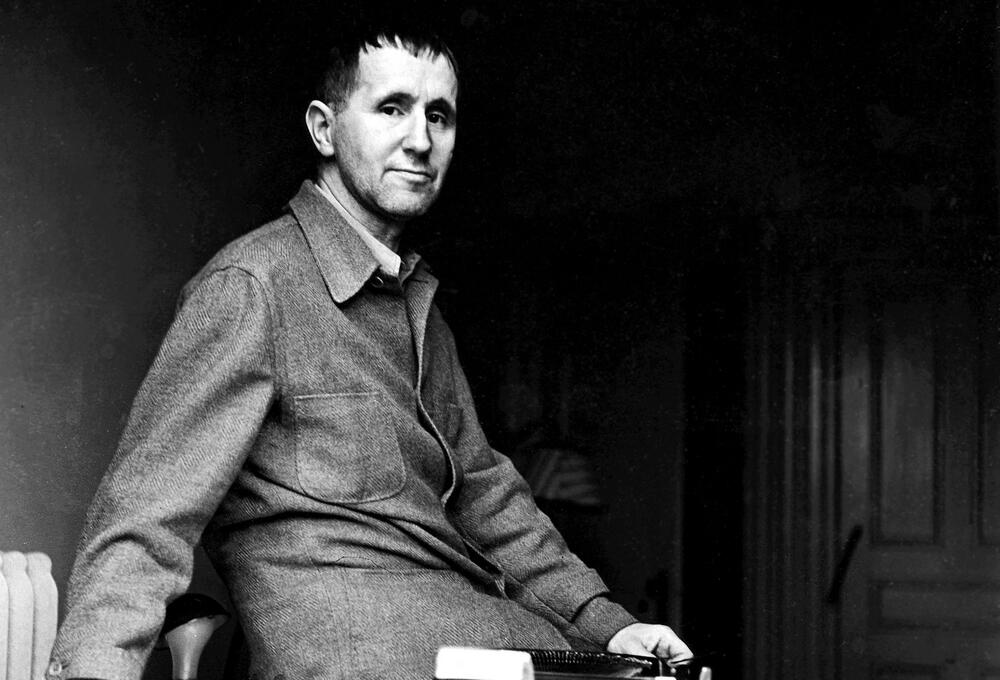

Heretic's coat

The German poet and theater writer Bertolt Brecht also published the novella "The Heretic's Coat" in his "Calendar Stories" from 1949. One passage says: “The guard came in the middle of the night between Sunday and Monday and took the learned man to the dungeon of the Inquisition. It happened on Monday, May 25, 1592, at three o'clock in the morning, and from that day until the day he climbed the pyre, February 17, 1600, Nolanac did not leave the dungeon. During the eight years that the terrible process lasted, he tirelessly fought for his life, but the fight against deportation to Rome, which he led during his first year in Venice, was perhaps led with the most desperation. The story with his coat belongs to that time. In the winter of 1592, while still staying at the hotel, he invited a tailor named Gabriele Cunto to make a custom-made coat for him. When Nolanac was arrested, the item of clothing had not yet been paid for."

The coat stayed with the host Moćenig, who denounced the guest. The tailor's wife wants money from the government. She doesn't care that a learned man dies, or gets sick in January without a coat in a basement cell. And Giordano is making great efforts all the time to get his treacherous host to return the coat to the tailor's wife. He does not manage to prevent his way to Rome, and thus to his death. But at least he didn't owe the tailor.

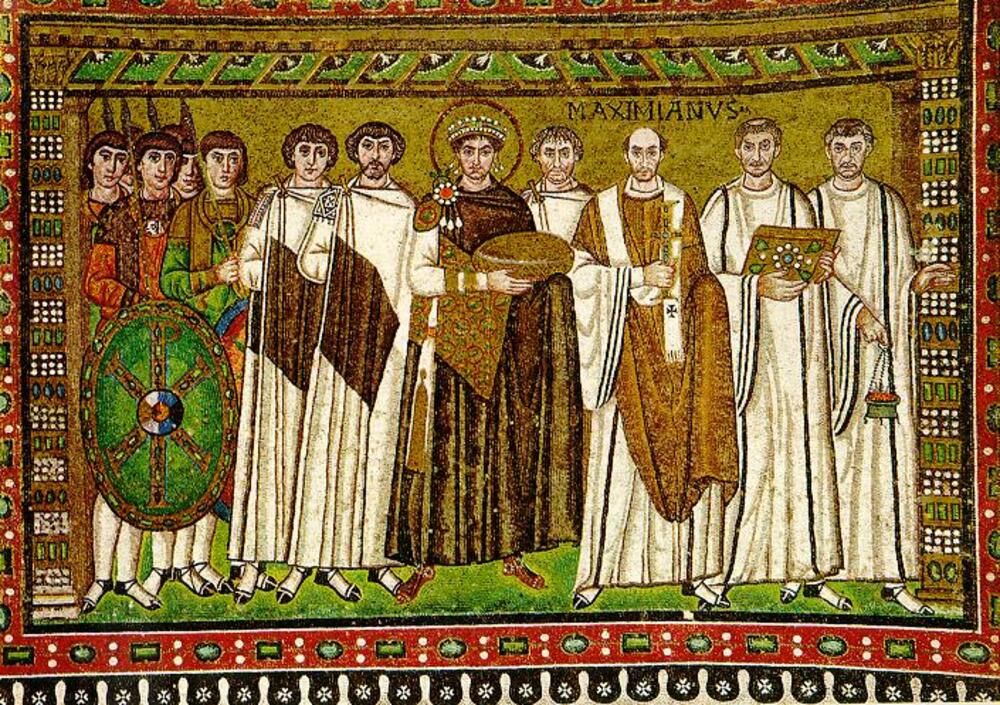

Brecht showed that Giordano Bruno remained a relevant human figure even in the bloody 20th century. As the plinth of the monument in Rome showed, he was not the only one who suffered because he did not parrot what the religious authorities were preaching. Since Christianity became the state religion, heresy has been suppressed by torture, fear, stake and sword. In the 6th century, the Byzantine emperor Justinian raised the fight against heretics to the level of state reasoning. And Peter's apostolic message received legal weight: "We therefore determine and command that only those who obey this law have the right to be called Christians, and that all others are madmen or fools on whose heads the shame of heresy falls. They can first expect the vengeance of God, so that finally We will punish them with the judgment that heaven inspires Us to do".

Only 424 years

Centuries of heavenly inspiration followed for harsh earthly punishments intended for "lunatics and fools." It should be remembered that the word heresy comes from the Greek word airosis - choice. Heretics are those who have claimed for themselves the right to choose what to believe. The shortest philosophical definition of freedom is - the possibility of choice. Heretics died because they wanted to live and think as free men. Upon learning of the verdict, Giordano Bruno said: "Perhaps with greater fear you announce the verdict against me than I receive it."

Let's go back to that Roman square. Perhaps, when I first saw the monument to Giordano Bruno, facing the Vatican, I thought with a cappuccino - it's good that those times have passed. I wouldn't want to spoil my own pleasure. But I remember a Tibetan monk and philosopher in a Chinese prison. An Indian-English writer under a decade-long Iranian religious death sentence. Cuban poets in the dungeon of happy Cuba.

The Ukrainian woman who wrote about corruption in Crimea is now in a Russian casemate. I think of cartoonists who slaughter in the name of religion. On a journalist who dissolves in acid and travels through Istanbul's sewers. On the American whistleblower who flees his country to Moscow because he published the wrongdoings committed by that country.

I feel like saying hello to Marko Vidojković, wherever he is. And to whisper to Giordano: "Only 424 years have passed. We have no excuse. But I can't think of anything else."

Bonus video: