Are "bloody" books the most significant books in the art of the written word? From the "butchering" under the walls of Troy, through the bloody hands of a Scottish nobleman and his lady, an ax in the head of an old Petrograd moneylender, to the carnival massacres of Judge Holden, the history of literature has shown that writers managed to enter the darkest spaces of the human soul, often unfathomable to the mind. , only when they would stare at the spilled human blood without flinching.

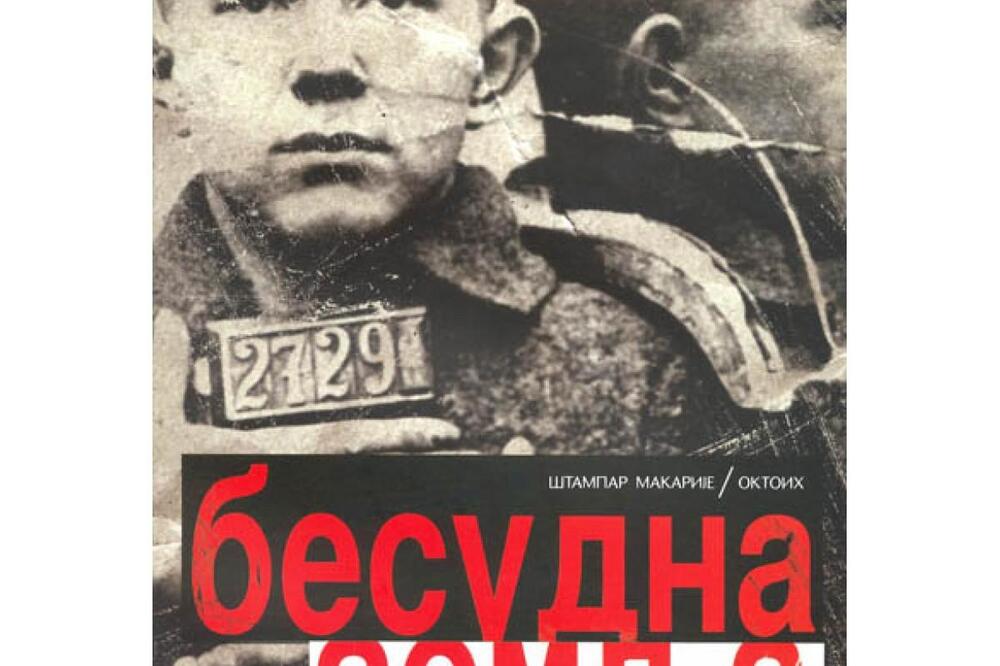

Besudna zemlja Milovan Đilas is one of the best Montenegrin literary works written from that unreduced perspective, thanks to which those neuralgias of our time that were mostly suppressed by the self-censorship sentiment of local writers became apparent. Already at the beginning of this novel, Đilas, going through his biography, will say: "It seems to me, I was born with blood on my eyes and bloody pictures in front of them." The first words were blood and bathed in blood", in order to continue that emblematic statement about the beginning of his life in a dramatic and ambient way with a slightly spooky image of the evening stories around the hearth that he listened to in his childhood: hour, and words do not allow the bloody events to be silenced."

The bloody stories of the era with which the author's childhood coincided will unfold from that picture, but in a way it will also be the initial narrative key from which the novel will be built. Among other things, with this thesis Besudna zemlja can be defended against those objections about the immature form, which were often meted out to this novel. Well, even without referring to those non-classical theoretical insights into the possibilities of the novel form - say Bakhtin's or Eagleton's, which allow the novel almost anything - in the process of building this novel, we can recognize what we could call the author's procedural awareness. Because the structuring of the form of the Landless Land is developed precisely on that image of an endless string of bloody stories around the hearth, and in Montenegro, along with warfare, this has always been one of the jobs of a high calling.

Which means that the fable, which at first glance seems like an oversimplified arrangement of stories, is not a consequence of the author's inability to develop a more complex structure of the novel, but rather the product of the intention to reflect part of the character of the space and era that the novel deals with through formal-structural solutions. More precisely - that the cult of storytelling, as a peculiarity of the given space, is transferred not only to the content of the text but also to its organization. The assumption about such an intention of the author is supported by a short but very effective remark in the second part of the novel: "If this is not a country for living, it is for talking."

What makes this procedure even more literary is revealed in the author's need to show how behind this story there is a deeper cause-and-effect relationship between objective reality and the experience of that reality. In the aforementioned key-image, Đilas creates a kind of causal sequence in which fire prompts words and "words do not allow bloody events to be silenced." Such a motivationally conditioned sequence makes "fire", "word" and "blood" become a kind of symbolic points in what we could call the Montenegrin destiny - from urge and agony, through the epic cult of storytelling (by fire, on the threshing floor, with the fiddle), to bloody wars, about which a new story is spun from which one goes into new blood, without the intention of getting out of that cyclical haunting. The narrator in this novel is a kind of Scheherazade who doesn't hold back, he leaves the narrative flow to the literal chronology without the intention of building some more astonishing fictional totality, but with a clear awareness of the form of the entire text, which is based on the mystification and fetishization of the sequence of stories.

Đilas's insistence on this phenomenon is also revealed in a kind of mannerism by which some stories are structured according to the same pattern. Thus, the beginning of the fragment about the Battle of Mojkovac, in the second part of the novel, develops in the same way as the aforementioned recollection of stories around the fire in childhood, with a rapid succession of images and situations in an almost identical rhythm: "The cannons are fired in the morning, and they don't let them rest in the evening; machine guns bark all night and bite every word and every dream, not leaving a single bud on the branch intact."

The theme of blood - boiled, spilled, vowed and sanctified, often pagan - in the first part of the novel, the great stories of wars and conflicts are reexamined, but through it the most neuralgic characterological and mental phenomena of Montenegro are also problematized. Revenge, as blood revenge, is the most intriguing motif of Besudna zemlje, it marks the fates of all the author's ancestors who appear in the novel, as well as almost all other families in their environment.

In this novel, Đilas reveals to us a somewhat hopeless picture of his homeland, in which this tangle of blood and revenge has become so embedded in the life of the community that it has almost lost its tragic dimension. In the Lawless Land, this non-incident of a phenomenon, which testifies to a society in which instincts have primacy over laws, is not only read in the acceptance of blood revenge as a legitimate customary mechanism, but also in the piety that reigns towards the avengers, and this piety has even moved into children. When the son of the man who tricked the author's grandfather into killing him was killed, suspicion fell on Djilas, but there was no evidence. Nevertheless, the author recalls how he and his brothers, who were children at the time, longed for these suspicions to become true: "This night murder remained forever dark and mysterious and it pressed on us when we were children, but more because of the desire to know for sure that the grandfather even if he was sanctified, but out of curiosity or guilty conscience." In another place, the author describes breaking up with his close friend at the time, whom he found out belonged to the family of his grandfather's killer: "We avoided each other and our friendship died down, without even admitting to ourselves the real reason - it's our chest too , still children, brektale with revenge."

The reason for the non-traumatic entrenchment of blood revenge in the consciousness of all generations should be sought in the Montenegrin code in which human life is not at the top of the value system. In those unwritten and deeply inscribed norms, he was always overtaken by honor and loyalty to the tribe, and because of them, blood was spilled without great dilemmas in the minds of those who risked their lives or deprived others. Đilas takes this ease of death, both in constant conflicts with invaders and in mutual satire, from the dominant epic tradition in the minds of Montenegrins, so in the novel, as in that tradition, the heroic dimension of death will be more present than the tragic one.

In addition, in the Landless Land, we can come across situations in which stories about bloody conflicts are not only devoid of tragedy, but represent entertainment for those gathered around the storyteller - while the vivid sequence of gorgeous images of bloody conflicts continues, there is no empathic "outburst" from either the inspired storytellers or the fascinated listeners. . The mechanisms of this seduction in storytelling are best seen in the author's somewhat ironic review of the story of his father's heroic endeavour, when in some battle a Turk arrived on horseback and cut off his head: "In stories it was more beautiful than a picture, but what was big like heroism: a head cut off in flight, with a key of blood, while the executioner is still on his feet... But no one seems to notice, neither while the story is going on, nor afterwards, that it was a human head..."

In this statement, the time determiner "nor after" has a special meaning intention. Because, if non-empathetic rapture is legitimate in an environment where the fire from the hearth illuminates the delighted faces of the storyteller and those who listen to him, then, nevertheless, it can be made incomprehensible that there is no sympathy for the bereaved even in the time of subsidence of the storyteller's passions. Simply, in a society based on epic Manichaeism, there were no such "little things". In this context, it is interesting that compassion appears only in the narrator, that is to say - the author, in the empathetic points that he sometimes sews for descriptions of bloody events.

This could be interpreted as the author's distancing from the moral and value principles of the epoch of his childhood and youth, but also from his youthful self, which calls for those opinions according to which Besudna zemlja is the product of the composure of a stormy biography. From that experience-laden position, the former passions and delusions sharpened, a discreet penitent tone broke through, and perhaps most of all, attitudes about the individual's place in history were rationalized. In those years, Đilas made a new self known in two genres - political-theoretical and fictitious - and both were denied to the public by political decisions.

But a lot has been written about it, and one could say that more can be written. What has not been written about enough is hidden in the in-depth critique of dehumanization, both of the mentality and of the system, because only in Besudna zelda Đilas showed that no one noticed that those heads that fly are human heads. The most important thing, however, is that Đilas implies that in that "nobody" there are equally the mentality, the regime, but also himself.

(Continued in the next issue)

Bonus video: