THE KEY MAN

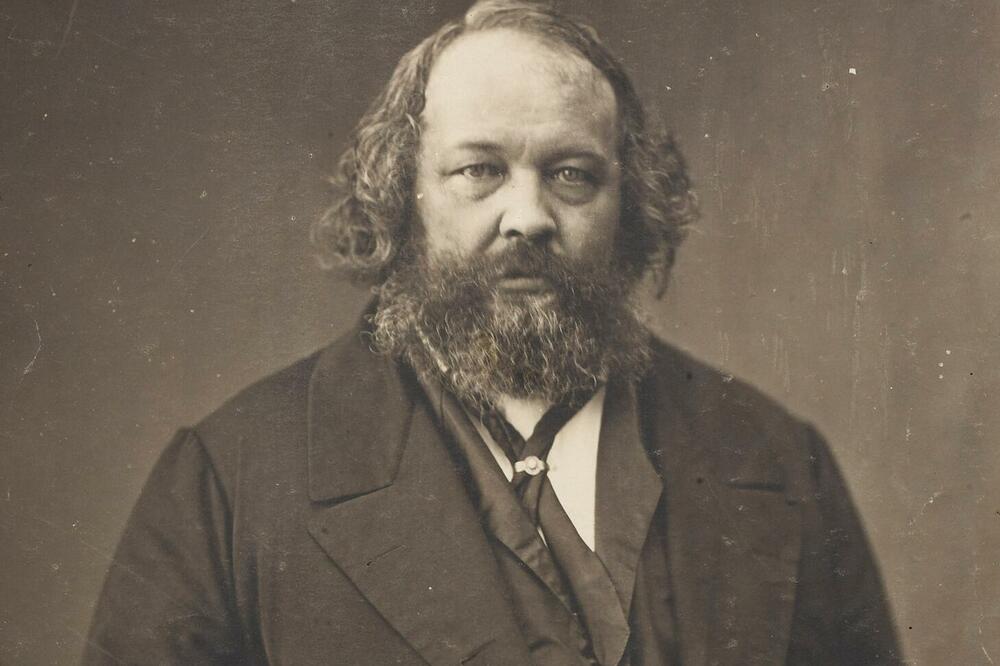

He is a key figure for the development and momentum of anarchism Bakunin.

In fact, only he, on the trail of intellectual heritage Proudhon i Stirner, but also in disputes with another grandiose figure of the era, Marx, constitutes anarchism as an elaborate teaching. "Anarchy is the natural tendency of the universe, and federation is the very order of atoms," wrote Bakunin, effectively and lucidly, which was always a feature of his texts and speeches. His insights are sometimes devastating, sometimes even far above the standards of his time, but always - convincing, suggestive, clear. There are few people who have so intensively influenced the opinion of an entire generation of European young intellectuals.

"Worker's freedom," writes Bakunin, "is therefore only a theoretical freedom, which lacks any means for its possible realization, and thus is only an invented freedom, a lie uttered." It is true that the whole life of the worker is but a continuation and terrifying series of conditions of service - voluntary from a legal point of view, but compulsory for economic reasons - established with an interplay of freedom accompanied by hunger. In other words, it is slavery.”

A HERO FROM THE SIXTY-EIGHT

Bakunin's theory implied the mandatory destruction of the state, in which he saw all the evil of bourgeois society. Instead of the existing society, a free federation of autonomous communities should be created. For him, freedom is the most important moral value of man. He argued with Marx, who ironically referred to him as the "Pope of Locarno". He gave a famous speech at the All-Slavish Congress in Prague.

The rebellion of 1968 restored widespread intellectual interest in his work. Bakunin wrote: "Every man, even the most intelligent and the strongest, is a producer and a product at every moment of his life. And freedom itself, the freedom of every human being, is the never-ending outcome of a large number of physical, intellectual and moral influences from other people who surround him and the environment in which he was born and in which he spent his entire life. To wish to escape from these influences in the name of some... self-sufficient and absolutely egoistic freedom is to strive towards non-being. The absence of this mutual influence is equivalent to death. In demanding the freedom of the masses we do not demand the absence of these natural influences of individuals and groups on the life of every man. All we want is the absence of artificially legitimized influences, the absence of privileges that these influences create." It is clear that this kind of rhetoric seemed close to the rebels of the Sixty-eighth. It also seemed fresh: Bakunin's spirit was released from the lamp...

Unlike Proudhon and later Kropotkina who tried to portray as faithfully and precisely as possible what anarchy, an ideal society should look like, Bakunin paid less attention to it, essentially actualizing and accentuating the critical potential of anarchism, i.e. a possible radical critique of society which, undoubtedly, works most destructively in the light of anarchist insights .

He is also much more interested in the possibility of revolutionary struggle, goals, and some problems that he lucidly observed. Numerous criticisms of the communist conception of the revolution will later be based on such considerations.

Bakunin, in relation to the contradictions of the ideal he strives for and the paths leading to its realization, finds himself in a position that is perhaps best illustrated by the powerful metaphor of one of the greatest poets of the XNUMXth century, the Alexandrian Greek Constantine Cavafy. In the poem "Ithaca", the greatest modern Greek poet, suggestively arranging all the troubles that awaited Odysseus on his way home, effectively points out that Ithaca is not an island, but Ithaca - the road to Ithaca. ("Wise as you have become, you will already understand what Ithaca means"). Bakunin, precisely on this track, ignores the futile debates about what an ideal society is, but deals with the challenges of the path to the ideal, which is to say - revolutionary action. And revolutionary morality. Bakunin effectively notices that concepts like the dictatorship of the proletariat, the hierarchical structure of the revolution, and the like, do nothing but reproduce all those bourgeois mechanisms that have already led to the accumulation of injustice. Why should any next time be different, asks Bakinjin. That criticism, primarily addressed to the Marxists and their concepts of struggle, will cost him his membership in the First International, from which he was expelled in 1872.

Bakunin is a philosopher and visionary who was sentenced to death twice, and spent twelve years in the dungeons of three empires. He was sentenced to lifelong exile in Siberia, from where he managed to escape in 1861 on a route worthy of a Hollywood movie - via Japan and America to the West. of Europe.

His conflict with Marx, which culminated in Bakunin's expulsion from the First International, represented a conflict between two irreconcilably opposed concepts - state, hierarchical and authoritarian socialism on the one hand and anti-authoritarian concepts of federalism and liberation on the other. Then Marx, before the court of the International, won, however the collapse of state socialism and reliable historical distance inexorably decided this dispute in favor of Bakunin.

RIGHT OF PROPERTY

Bakunin is radical in his views, but consistent. His insights sometimes strike at the foundations of the Western world. Early anarchists understood that one of the fundamental problems generating social injustice and exploitation was property. But look at how Bakunin writes about it and imagine what impression it left on his contemporaries. "The only thing that the state can and must do is to gradually limit the right to inheritance, in order to reach the complete abolition of itself as soon as possible. We argue that this right will necessarily have to be abolished because, as long as there is a right to inheritance, there will be inherited economic inequality - not the natural inequality of individuals, but the artificial inequality of classes - which will necessarily continue the inherited inequality of development and intelligent cultivation and will remain so. source and endorsement of political and social inequality.”

A POEM ABOUT REBELLION

From today's point of view, and in the light of all those new challenges of current reality, the unimaginable acceleration of living has made our post-industrial world immeasurably more complicated than the early industrial world of the second half of the XNUMXth century, because some of the most important forms of exploitation have become much more subtle, "less visible", since that the media civilization puts all its (enormous) power into the function of new capitalism, Bakunin's apotheosis of the human power of rebellion is exciting and intellectually superior.

Bakunin "builds" his "poem about rebellion" like this: human nature, he says, differs from the animal context from which it arose, in two respects. Man has the power to think and the need to rebel. "These two abilities, and their creative collaboration throughout history, form a creative factor, negating the factor in the positive development of human animality, and creating, at the same time, everything that is human in man," writes Bakunin. He sees rebellion as the most important part of human nature and human identity, because the highest value - freedom - corresponds to rebellion. Bakunin believed, and this is hard to dispute, that at the core of every rebellion is the hunger for freedom.

And science is the key expression of that other human ability that constitutes it - the power of thinking. Therefore, Bakunin believed that the development of humanity, the so-called progress is nothing but an endless story about the humanization of everything - man himself, the institutions he creates, but also the nature that surrounds and limits him.

Along with the instinct of rebellion, which Bakunin detects as the key motive and the most important force of the global process of liberation, the great thinker also speaks of the instinct of striving for power, anticipating some of the meaning nuances of what will happen in the revolutionary Nietzsche's thoughts take on true dimensions and shine with the full splendor of true insight.

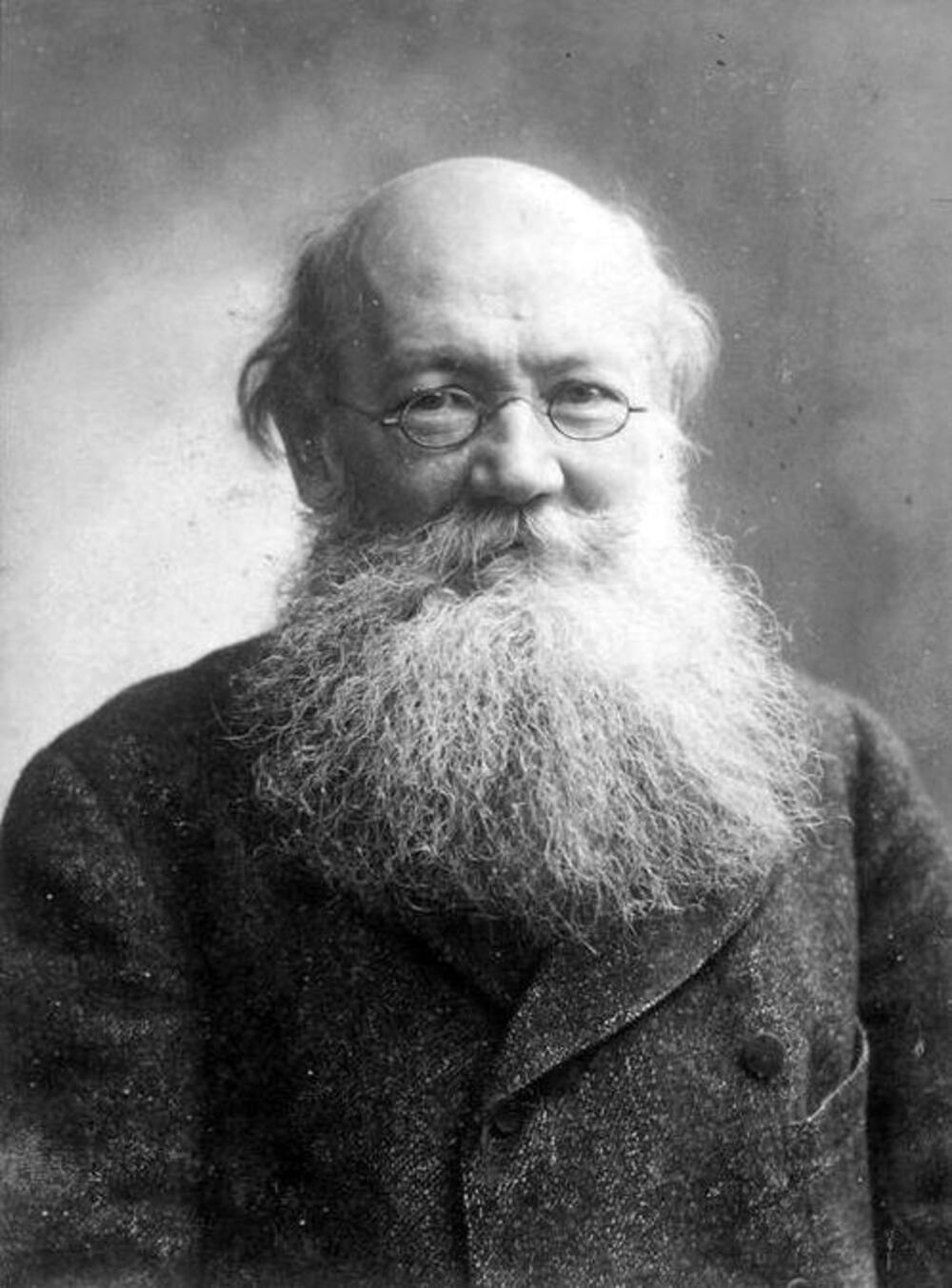

KROPOTKIN, PIERRE ALEKSEJEVICH, PRINCE OF ANARCHY

In Kropotkin's work, "everything is connected with everything, and without knowing one, one cannot understand the other."

Today, the breadth of Kropotkin's scientific work is almost unclear. Natural sciences, geography, sociology, philosophy - everything for him was in the function of liberating man. Realization is the most powerful form of liberation. To the apotheosis of the People, which was completely in the spirit of the times (the "Going to the People" movement), Kropotkin adds the apotheosis of Nature, and the resulting apotheosis of Science, which is a kind of language for understanding nature and man. Therefore, on that track, his anarchism has a kind of anthropological foundation. Kropotkin even believed that ethics derives from the laws of nature.

Kropotkin's concept in theory is called anarcho-communism. Kropotkin himself emphasizes that the goal of anarchists is the realization of communism. "But", Kropotkin immediately clarifies, "our communism is not the communism of phalansters or the communism of German theoreticians-statists. It is anarchist communism, communism without government, communism of free people. It is a synthesis of two goals, which humanity is eternally striving for - economic freedom and political freedom." ("Records of a revolutionary"). As he notes Dr. Zoran Djindjic in the preface to that particular book, he wanted to free anarchism from its internal contradictions, to create a scientific system from it, which would be practically applicable. In the end, Kropotkin linked the anarchist project to the further development of science and the momentum of industry, and he saw morality as the basic driver of the aspiration for liberation. But there remains the link with Russian populism - as a trace of the context in which the thinker himself was formed, his central idea of the masses as the main generator of historical processes remains.

Kropotkin, in fact, rejects Proudhon's methods of a peaceful, gradual and evolutionary, "deep" revolution, but he is also skeptical of Bakunin's belief that it is the spontaneous movement of the people that destroys old social frameworks and structures. Kropotkin believes that "conscious action of the people" is necessary, which must be armed with "knowledge, hope and moral principles". This is where the role of the conscious minority comes to the fore, since, according to Kroptkin, it must bring the people to a state that he considers optimal for "conscious action". And the way to that is education, science and the need to help the oppressed, which clearly follows from moral convictions and human nature based on solidarity and the need for mutual help.

In order to prove this thesis, Kropotkin wrote a book he called "Prosperity for All - Agriculture, Industry and Crafts" (1899). He claims in this book that, even with the existing level of productive forces, arable land and mineral wealth, as well as with the use of technology that is at the level of the time, and even at the level of the pre-industrial revolution, there is a completely "satisfactory material basis for the realization communist anarchism".

AGREEMENT OF THE PEOPLE AND THE ARMED LEGIONS

Political as well as economic assumptions have a decisive influence on Kropotkin's "reconstruction" of the origin of law and the class state. Kropotkin elaborates the thesis that law was created by a contract between the people and the armed legions. That contract was not a voluntary act, the people were forced to it physically and economically, explains Kropotkin. The principle that Kropotkin wants to explain is very similar to what today, in the terminology of the underworld and crime, we know as a "racket". You are not in real danger, but you have to pay protection to someone who could otherwise put you in danger. So, the only danger for you is the one who claims to keep you out of trouble. For Kropotkin, this hypothetical situation of the "birth of law" from the contract between the people and the armed legions is an ideal illustration of the dual nature of law: law rests on the elements of ethos, but equally on the instruments of power and coercion belonging to the ruling minority.

Kropotkin's judgments, thanks above all to the breadth of his education, but also to the need to subtly and nuancedly grasp the being of history, are devoid of any exclusivity or fitting of facts into the Procrustean bed of his own theory, which is not a rare case, even among lucid thinkers.

He thus admits that the idea of legal equality played a positive role in the fight against monarchy and feudalism, but that, after the French Revolution, the idea of legal equality functions as a particular class concept. "In civil society, the purpose of the law is to protect private property and maintain administrative authority, therefore, to support the maintenance of the system of late exploitation," writes Kropotkin.

His words from the book "Anarchism and Morality" sound like a political call, but also a cry of liberation: "We are fighting against all those who want power... With our fight for the full liberation of the individual and society, we are opening a new chapter in cultural history, the flight of humanity towards ever higher self-improvement. Enough of political power. Make room for the people, for anarchy."

THE PEAK OF THE HEROIC PHASE OF ACHARCHISM

In the classic phase of anarchism, in the epoch of the constitution of anarchist teaching, Kropotkin is the final point, the peak that will be followed by a decline, fatigue, an era of vain fights and polemics, and a new momentum will only come with the twenty-year political acceleration. The revolutions in Russia and Spain, as well as the emancipatory movements in Latin America, as well as the student rebellion in 1968, will be events that will bring new shine to anarchism, and new significant theoreticians and workers.

After Kropotkin, the successors of anarchist thought up to the listed political and historical challenges will mostly repeat Kropotkin's and Bakunin's conceptions, without significant contribution, and without new moments in the theory itself.

However, it is these new challenges that will show the scope and importance of their insights. Zoran Đinđić writes "It is no coincidence that the European student movement, fed up with classical schemes of power, looked for its own classic in Kropotkin".

In his old age, Kropotkin experienced a grandiose historical episode - the October Revolution. His attitude towards October was, for understandable reasons, ambivalent. "Despite all its faults (which, as you know, I know very well), the October Revolution brought enormous progress. She showed that a social revolution is not impossible, as it has come to be believed in Western Europe. Despite all its shortcomings, it represents progress in the struggle for equality, which will not be destroyed by attempts to revive the past," reads Kropotkin's letter. Lenin.

LAST PERFORMANCE

Kropotkin met several times with the Bolshevik leader Lenin, who held him in high esteem. Because of this, although he protested, he was spared the persecution of anarchists that followed the Bolshevik takeover. In 1918 he retired to the village of Dmitrovo.

When Kropotkin died in 1921, Lenin ordered that all anarchists be released from prison for one day. So Kropotkin's funeral was the last manifestation of anarchism in the USSR. Posthumous for both Kropotkin and Russian anarchism. This bizarre data clearly shows two things - how much Lenin appreciated Kropotkin, but also how harmless and destroyed anarchism in the USSR was already. So the leader could allow himself such a benevolent performance... There are also photos from Kropotkinp's funeral. A crowd of people, black and red anarchist flags, slogans. After the funeral, they were all returned to reliable Soviet prisons.

Kropotkin, the youngest of the "fathers of anarchism", built his anarchist teaching most systematically. His ethics, as well as social criticism, are still inspiring and convincing achievements of the time that was marked by the spectacular intellectual ferment of the XNUMXth century. A nobleman by birth, he did not believe that by birth one gets anything except human authenticity, which must be built. Yet even in his thought there is a refinement that cannot be taught.

Bonus video: