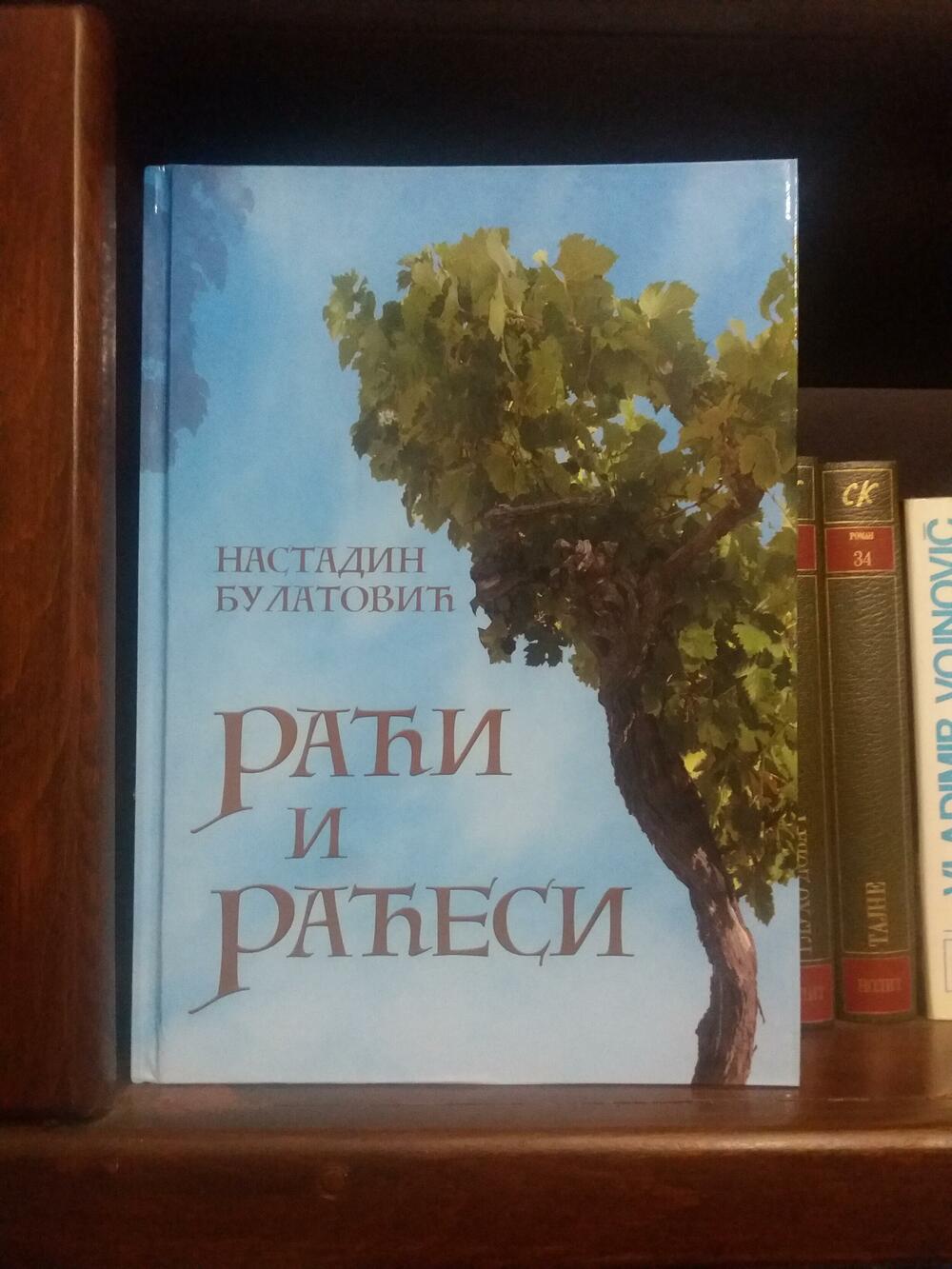

(Nastadin Bulatović: "Raći and Raćesi", Kuča Development Fund, Podgorica, 2021)

Even today, as a hundred years ago, in the tame village of Raći, not far from Podgorica, in the heart of Kuč, there are only about thirty houses. What would he do? Nastadin Bulatović that by any chance there are still at least that many?!

His "chronicle of a village", a completely atypical monograph, a mix of documents, quotes, legends, stories of village memories, records of village priests, personal memories, anecdotes, recipes, various ethnographic materials, contracts, financial reports...

From that material of all colors and textures, a picture is created before our eyes that could be signed by most villages in Montenegro. Image like Lubardine. A living, flickering image full of light, beauty, but also the deepest suffering, sacrifice and suffering, immeasurable kindness and humanity.

Water

The predecessors of the Slavs, the Illyrian tribes, the Bukumirs, the Vlachs...

The tame village of Raći, where the famous Rać vine grows, was inhabited even before the middle of the 15th century when it was first mentioned. At one time it was completely deserted, and then it was inhabited by the people of Rovčani. Blood revenge, Turkish attacks, but also domestic evil are inevitable. Battles (Novšići, Bregalnica, Skadar) and wars follow. Great suffering at the beginning of World War II, fugitives, camps, partisans and Chetniks, residual bombs. Letters from America. Decades without water, electricity. Fewer and fewer children. Herds are disappearing. And lakes.

But there are also those who return in the 21st century, restore the neglected, build roads through bare stone. They respect their ancestors, their grandmothers' bent backs hurt from the burden, they are proud of the successes of their natives. And they do something - for good.

During the renovation of the church of St. Elijah in Raći, their Momir Bulatović among other things, he says: "It's not easy with us. We are a difficult people. There is a lot that needs to be set in stone to be good and come back to."

Heavy, because he lived hard. There was no water in Kuči. The story about oysters seems to have been torn from an ancient legend: "Rainwater was collected in oysters, which often meant life." The summer heat and tiredness after hard leaf picking forced them not to miss the heated water in which birds or snakes had previously bathed. There are also oysters in the caves, in the Windmill and the cave at the foot of Zavalica. The water in the caves was always cold and cleaner than that from the open oysters." (In the caves, the author reminds, shepherds hid from thunder, villagers from the invasion of enemies, monks from noise. Sometimes there are pigeons in the caves, and maybe treasure.)

"During great droughts, people from the village went to the springs in the bed of the Little River to get drinking water. It took three to four hours to walk in one direction." There was also a lack of water in the mountains, in the katuns. That's why they melted the snow, taken out of the pit. They struggled to build bisters in the future, saved money.

Heroine

"Our grandmothers and mothers used to go to rasvit to collect snow. After harvesting logs with an ice load of over 50 kilograms with axes, they returned with one or two short rests and arrived in katun with the first rays of the sun.

Even today, I seem to see them bent over, with flushed faces, approaching each of their huts, eager to be relieved of their heavy burden. Water was pouring from their backs, it is not known whether it was more from sweat or from snow logs. There was no time to rest after arriving in katun. New duties awaited - milking the cattle, making varenika cheese, preparing lunch for the family..."

These pictures look unreal today. Nastadin Bulatović will devote a special chapter to the women of Rać for a reason. Carefully and tenderly, they will show us their pain for their loved ones who died in the war and for extinguished hearths, courage and strength, loyalty to the family, quiet sacrifice and nobility, gentleness. They promote Ćuba, Spasa, Milica, Stanica, Golja, Novko, Pejko, Jevrosim, Sen, Anđa, Miljuša, Milev... in long black dresses and scarves tied under their chins, for the rest of their lives. Young widows in a village full of orphans.

"After the Second World War, when most of the children from Rać became orphans, our mother Janica demanded that we call her and our father by their first names so as not to hurt our peers in the village who were left without fathers, Milosava remembered her mother's decision."

Women worked in the fields during the day, the hardest jobs. Night hours were reserved for knitting socks, sweaters, mending torn clothes. Hundreds of loads of hay, leaves, barrels full of water, logs of snow, bent their backs, bent their spines. In order to obtain basic necessities, they traveled for days, over the mountains of Kuka and Albanian Vrmoša to Gusinje, or to Shkodër, a hundred kilometers away. And they walked more than twenty kilometers to Katun, so it would happen that they would give birth near the nearest beech tree.

In the chronicle of the village of Raći, in a picture like Lubardina, the figure of the mother dominates and miraculously multiplies. The black scarf falls to reveal the dewy forehead, ruddy face and bright eyes of the woman in labor who quickly wraps her baby and - continues on her way.

Secrets

A monograph is usually based on data, verified facts. And in the book "Raći i Raćesi" there is so much that is blurred, unclear and unknown, possible and impossible, mysterious, therefore - literary. And that's exactly what gives it its charm:

"It is unknown when and why the former inhabitants left the village of Raće."

"It is not known for sure what stone piles, burial places or meeting places are, and even less is known when they were created. As a possible time of their origin, the era in which the Balkans were inhabited by the Illyrians is mentioned.

"Who was the monk or monks who chose a small cave at the top of the hard-to-reach Sokolište for their ascetic life?"

There is a popular belief that there is a treasure hidden somewhere in the area of Velješa, and here is a legend about the relocation of the monastery.

When the church with loopholes was built - it is not known. The disappearance of church bells is also a secret.

The name of the benefactor who saved the icons from the church of St. Elijah, when it was leaking, will also remain unknown.

Isn't the image of the grape harvest in the village a fairy tale: "The harvest lasted for days, and the grapes were placed in canopies made of wicker, which were loaded on horses, donkeys, or carried on the back. It happened that the harvest was so great that there was no place to store the grapes, so concrete basins were hastily poured or they waited for the first harvest to ripen and only then picked the rest of the grapes."

Vocabulary and warmth

Did you know that dry city - lingering wind? And what are they precombs?

The book "Raći Raćesi" also contains linguistic treasures. Not infrequently, the reader stops before the freshness and light of a word that he is not sure about - whether it originates from the time of the Duke of Kuč Miloš Bjelomužević, was it produced by Mrtvo Duboko from Rovac, or is it perhaps the author's coin?! In any case, a lot of fine material to study. But also for inspiration. Only toponyms can build the structure of a fairy tale: Treskavac, Momonjevo, Stravče, Mačkovica, Sokolište, Guzovalja, Gladište, Trepetljikov do, Đurđenov katun, Vodna pečina, Biskupova dolina, Suvi potok...

Nastadin Bulatović did not try to "objectify" his book. And when he talks about the people he knew, and about himself as a ten-year-old who crosses the Treskavac pass at night with his mother, terrified, driving the pigs into the village, and when he conveys the memories of others - his warmth is natural, stemming from understanding and love, the portraits he paints in a few strokes or through characteristic scenes full of emotions: "Vidosava's burning sun, around which she lived her whole life, remained fiery."

"Jagoš's favorite drink was vine. His family had one of the largest vineyards in the village, which produced ten tons of grapes. On one occasion, when they were about to make brandy, Jagoš's older son Mihailo asked him how many vines he should leave for the housework. He didn't wait long for Jagoš's answer:

- For me, leave as many liters as there are days in the year, and for other household needs, you see. And it was like that for years. We said that Jagoš, with a glass, lived to a ripe old age, denying all the doctrines of the medical profession and science and proving that brandy, even if drunk to excess, does not necessarily harm health."

"Rarely any of the hosts from Rače that I remember looked forward to a guest like Raško. He would get the child out of the chair if they entered his home."

"If I could, I could write a film script about the life and work life of Milonja Ivanova Bulatović. More arduous and suffering life from birth to death on the one hand, and optimism and cheerfulness on the other hand, it was difficult to meet as in this man."

This is how Nastadin Bulatović wrote in the chronicle of his village. We are sure that even if there were only three houses in that village, he would have managed to paint something that could be put in stone.

Bonus video: