American writer John Bart, one of the first authors whose novels and stories were labeled "postmodernism", died on April 2, 2024 at the age of 94. On this occasion, we are broadcasting an interview he gave for the Paris magazine in the spring of 1985.

***

This interview with John Bart was conducted at the KUHT studios in Houston, Texas, for the show titled A writer in society. The scenography was arranged to resemble a writer's study, and the decor included a small globe, a bronze figure of an animal similar to Remington's, an upright shelf with glass shelves on which potted plants were placed, and randomly arranged books, including several editions of abridged novels in edition of Riders Digest.

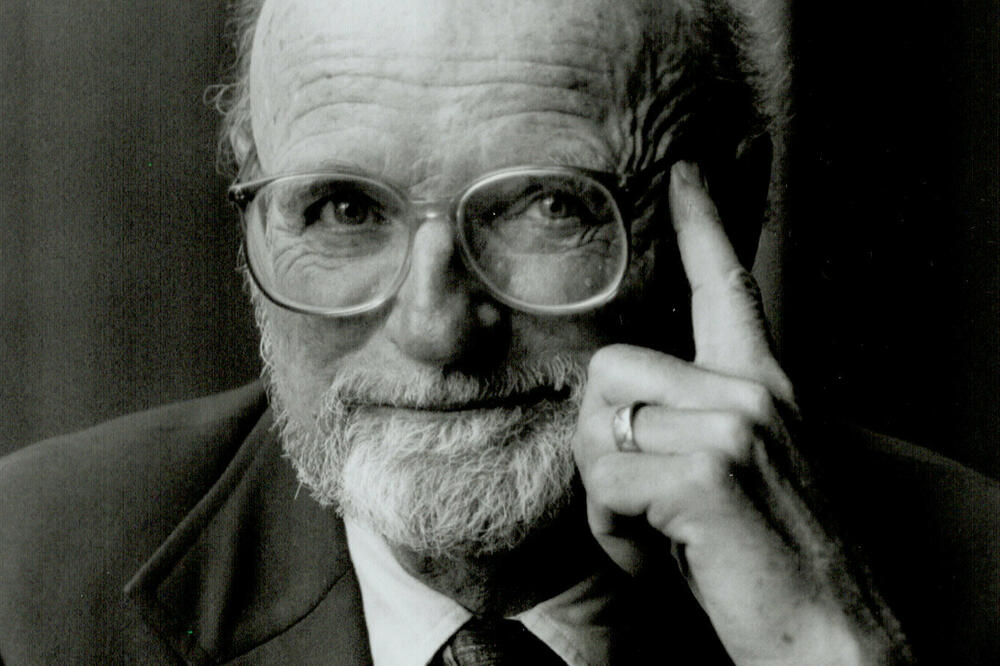

Large pots of plants were placed around. Bart sat between them, in a wicker chair. He is a tall man, with a high dome-like forehead; a pair of glasses with very large frames make him appear professorial, owl-like. It's a real treat for cartoonists. Maintains a thick straight mustache. He also recently grew a beard. By the way he carries himself, Bart is described as a combination of a British officer and a Southern gentleman.

"We must stick to the canal," he wrote in his first novel, Opera on the water, "and let the tributaries and gulfs flow". In every novel after that, he broke that order to stick to the main theme. He was particularly influenced by cyclical narratives such as Bartonova One thousand and one nights i Gesta Romanorum, as well as the complexity of such modern masters as Nabokov, Borges i Beckett. Because of the novels, characterized by a wide range of erudition, invention, vivacity, references to history, whims, austerity and a great wealth of motifs and style, Bart is described as an "ecologist of information".

Bart, talking about his work habits, says that he gets up at six in the morning and turns on the electric kettle in the kitchen, so that when he sits at the table for six hours, he has an excuse to walk from the study to the kitchen and go get a cup of coffee. He does not measure his work in days (as he used to do Hemingway), but by months or years. “That way you don't feel terrible if you put together three days without going out with God knows what. You don't feel blocked".

This interview, as it was limited to half an hour of conversation in front of a television audience, seemed too short for the usual standards of the magazine. It was assumed that Bart, being a master of verbosity, would surely add something.

Additional questions were sent to him. The interview was returned to this newsroom with unanswered questions, and the text of the conversation was edited and shortened. Maybe Bart didn't even notice the follow-up questions. The interview was sent to him again, this time with a small fee attached for the extra hassle. The interview was returned again, along with an uncashed check, with the following statement: “I am sorry to hear that our interview will probably be the shortest you have ever printed. In fact, it is now even a little shorter than before. You better not send it to me again!”

When did it all start? When did you actually realize that writing was going to be your profession? Is there such a moment?

It seems that this happens later in the lives of American writers than in European ones. American boys and girls don't grow up thinking, "I'm going to be a writer," as they say Flaubert; at about the age of 12 he decided to be a great French writer and, by God, he turned out to be.

Writers in this country, and novelists in particular, enter it somehow through the back door. Almost every writer I know wanted to be something else and then found themselves writing with some kind of passionate dedication. In my case, I thought I was going to be a musician. And then I discovered that, although I had an amateur streak, I didn't have enough of a gift for professional development. And so I went to John Hopkins University to find something else to do.

There I found myself writing stories and making all the mistakes that novice writers tend to make. After writing enough bad pages for about a novel, I realized that not doing it right is exactly what I want to do. I don't remember if it came to me as a sudden realization, or as an exciting experience, but it was like a complete recognition that, for better or for worse, this is how I will spend my life.

The advantage at "John Hopkins" for me was that I had a wonderful old Spanish poet-lecturer, with whom I read Don Quixote. I can't remember anything he said about Don Quixote, but old man Peter Salinas, died, a refugee from Franks Spain, embodied in my innocent, ingenious eyes the possibility that a life devoted to making sentences and telling stories could be dignified and elegant. Whether the works themselves turned out to be dignified and elegant is another question, but I think my experience is not so unusual: you decide to be a violinist, you decide to be a sculptor or a painter, but you find yourself a novelist.

What musical instrument did you start with?

I played the drums. I hoped to end up being an orchestrator, which is what is called an arranger these days. An arranger is a guy who takes someone's tune and makes it work. For better or for worse, my career as a novelist is like that of an arranger. My imagination works most easily with old literary conventions such as the epistolary novel or classical myth, along with received melodic lines, so to speak, which I later re-orchestrate for my own purposes.

What's the first thing you do when you sit down to start a novel? Is it a form, as in an epistolary novel, or a character, or a plot?

Different books start in different ways. Sometimes I wish I was one of those writers who starts out passionate about a character and then, as I hear from other writers, just give the character free space and see what it is that he or she wants to do. I'm not that kind of writer. Much more often I start with a shape, form, maybe a picture.

The steamboat on which performances are held, for example, which became a central image in Wash in water was a photo of a real steamboat for the shows I remember seeing as a boy. Turns out his name was Captain Adams' original unsurpassed water opera, and when nature, in its clumsy way, gives you such a picture, the only thing a person can do honorably is to create a novel out of it.

Perhaps it is not the most noble approach. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, for example, approaches the literary medium with a highly moral goal; he wants, literally, to try to change the world through novels. I respect and admire that intention, but just as often a great writer will approach his novel with a far less lofty goal than the desire to undermine the Soviet authorities. Henry James wanted to write a novel in the form of a sandbox. Flaubert wanted to write a novel about nothing. What I've learned is that a muse's decision to sing or not to sing is not based on the loftiness of your moral cause - they will sing or not regardless.

What got in your way that you had to remove?

What got in my way? Chekhov he notes to his brother, the brother he always scolded in his letters: "What the aristocrats get for granted, we pay with our youth." I had to pay school fees in that sense. I come from a rather unrefined family from a rural area on the southern Eastern Shore of Maryland, which is very "Deep South" in its mentality. I went to a mediocre state high school (which I enjoyed), got into a good university thanks to tuition, and then had to learn, all over again, that civilization existed, that literature lasted. That kind of innocence is the opposite of the extraordinary sophistication with which Vladimir Nabokov approaches the medium, he already knows it, as if he had been in the loop from the very beginning.

Were there any special guides that helped you?

Great guides were the books I discovered in the Johns Hopkins library, where my student job was to distribute and arrange books. There they would more or less encourage you to take a cart with books, go among the shelves and not come back for seven or eight hours. So, I was reading what I had lined up on the shelves.

My great teachers (and that is the best thing that can happen to a writer) were Scheherazade, Homer, Virgil, Boccaccio, as well as the great Sanskrit storytellers. I was forever impressed by the breadth, as well as the depth, of literature, and that was exactly what a kid from the swamps, in my case, needed.

When you were flipping through books in libraries, were you fascinated by the very idea of telling stories or was it the characters from the works you were reading? What was it that started the spark?

They weren't characters. I might be a better writer in the realm of characterization if that were the case. No, it was more of a mass narrative. My apprenticeship was rather a kind of Baptist total immersion in the "ocean of rivers of stories", which was the name of one of those Sanskrit works I read when I was filling the shelves... Volume by volume, until the seventeenth book. I think the sweetest kind of apprenticeship a storyteller can go through is that kind of immersion in the waters of narrative, where you absorb early on by osmosis what a gifted writer usually learns eventually: controlling the pace of the narrative, leading the story.

How confident are you in the house of fiction or, as you say, on the steep slopes?

Regarding your position in the giant slalom of the Muses?

I don't mean in the eyes of others, but in your feeling about what you intend to do.

It's a combination of almost obscene self-assurance and constant terror. You remember the old story about how Hemingway always recorded the number of words he wrote that day. When I learned about that detail about Hemingway, I understood why the poor guy faltered and ended up in an accident.

The average professional, whether good or mediocre, finds enough self-confidence to no longer fear a blank sheet of paper. As for my fiction: my friend John Hawkes he once said about it looking like purring against nothingness, so there just shouldn't be any peace there. I got it.

That is the horror of Scheherazade: the horror that comes from the literal or metaphorical equating of storytelling with living, with life itself. I understand that metaphor to my very core. I always have the feeling that when the story ends, maybe the whole world will end; I wonder if the world even exists when I don't tell about it. So, at this stage in life, I trust myself enough to know that the page will fill up. Indeed, since I'm not a very consistent writer (my books don't resemble each other much), the constant curiosity makes me want to see what happens next.

Stendal said that once, when he wanted to commit suicide, he could not bring himself to do the act because he wanted to know what would follow in French politics. My curiosity is similar… when this long endeavor is finished, what will be written on the next page? I have never been able to think so far ahead; I cannot do this until what is in my hands has left the shop and passed through the printing presses of the publishers. Only then do I start thinking about what's next. I'm curious as a new guy. Maybe more.

And when it comes to the middle of the book? Do you know what will be on the next page then?

There are writers blessed to be able to think of three novels in advance or to write two or even three at the same time. I'm not the one.

No, I mean the same book. Do you know what the last sentence could be when you start?

I have a pretty good sense of where the book is going to go. By temperament I am an incorrigible formalist, unwilling to embark on an undertaking without knowing where I am going. It takes me about four years to write a novel. Embarking on such an undertaking without the slightest idea of when and with what land I would land would be quite unnerving.

But experience has taught me that there are certain obstacles you cannot cross until you reach them; in a matter as long and complex as a novel, you may not even know the true shape of the obstacle until you see it, much less how to overcome it.

Those are the climactic moments you know you're going to have to deal with?

Yes, important moments that I know from my sense of dramaturgy that I will have to deal with: the guns that have to go off.

Like the Marabar Caves in The Road to India?

Exactly. It is this tension in the writing process that I have learned to be simultaneously delighted and - mildly, measuredly - terrified of.

When you start work in the morning, do you first re-read for a while what you did up to where you left off the day before?

Certainly. Partly to get into a rhythm, and partly it's a kind of magic: it seems like you're writing, even though you're not. The process is set in motion, the wheels begin to turn. I write by hand. My neighbor from Baltimore Anne Tyler and I may be the last two writers who actually still write with a pen. She noticed that there was something about the movement of the muscles when putting pen to paper that brought her imagination back to the route she was on. I feel it too, pretty well.

Do you think word processors will change the styles of writers in the future?

We could. But I remember my colleague from "John Hopkins", the professor Hugh Kenner, when he said that literature changed when writers started creating at the typewriter. I raised my hand and said, "Professor Kenner, I still write with a pen." He replied: “It doesn't matter. You breathe the breath of literature written on a typewriter”. So I guess my fiction will be text processed by those links, even though I won't become a blue screen user myself.

At one point in Lost in the House of Laughter you scold the reader for reading…

It's dangerous to do that.

… and you say he should be staring at the wall or doing something like that. Do you believe that or were you just having fun?

That was the mood of the character in that story, To the life story, and that also, in my opinion, corresponded with the apocalyptic mood in our country at that time: the late sixties, when our republic was enjoying a more than usual apocalyptic atmosphere. A similar kind of apocalyptic premonition surrounded the question of the future of the press in general, and of the novel in particular.

It doesn't excite me that much. The essence of a couple of essays I wrote, as well as some of the stories, is that the death of the genre does not mean the death of storytelling; storytelling is older than any form of novel. I have to say, though, that my sense of priorities in that matter has changed.

U Wash in water, that first, very youthful novel of mine, the hero, a man at the age I am now (in my early fifties), the heart in a specific state made him wonder in life, as he moves from sentence to sentence, whether he will reach from subject to predicate, from predicate to object. The characters in the novel I'm working on now, somewhat similar to the characters in the previous novel, Sabbatical, he is much more concerned about whether the world will survive, let alone the novel.

Joyce Carol Oates she once said that she doesn't like the "pop apocalypse". Although I like that expression, it seems to me that the question of the literal survival of civilization, on this powder keg we are sitting on, is a much more meaningful question than the extremely trivial topic of whether a particular literary form has rung its bell or will die out in the next two hundred years as happily as it is dying out the last two hundred years.

Do you think the novelist can influence any of the ominous things you talk about?

I don't think we, as a group, would be any better at running the world than these people who screw up. Poetry does not set events in motion. Artists committed to politics like Gabriel García Márquez they are honest in their political passions without major damage to the quality control of their art. But are they really changing the world? I doubt it, I doubt it, despite the objection that it is Abraham Lincoln said Harriet Beecher Stowe: "So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war!" Well, it's not. No. Without intending to sound so terribly decadent, I rather like the late Vladimir Nabokov's remark about what he sought from his novels: “aesthetic bliss”.

Well, that sounds too decadent indeed. Let me switch masters for a moment and say that I prefer Henry James' remark about the writer's obligation - which I also consider his obligation - to be interesting, to be interesting. To be interesting from sentence to sentence. To be interesting, not to change the world.

I've always loved the conversation between William Gus and John Gardner where Gardner says he wants everyone to love his books, and Gus retorts that he wouldn't want that any more than he wants everyone to love his sister or daughter. Which side is closer to you?

Gas accused the late gentleman Gardner confusing love and promiscuity, which are not the same. Well, I'm a novelist by nature and temperament. The novel has its roots, most honorably, in popular culture.

Despite the art of the novel, I think many of us novelists secretly wish for both, as Charles Dickens or Gabriel García Márquez did to some extent, to write novels that are disturbingly beautiful and popular at the same time. Not to make a lot of money, but to be able to reach out and touch hearts - no, that sounds corny, doesn't it? But that's what most novelists want to achieve - to reach a little beyond the audience of professional readers, those who are really dedicated followers of contemporary literature.

It is the guiding star for navigation by which I confess to be guided. But I am, in fact, an amateur sailor and therefore an amateur navigator; I don't confuse my guiding stars with my destination. None of my novels have experienced that kind of popularity, and I don't expect any of them ever will. But it's a good dose of luck when it happens. I think that the novel in that sense is an essentially American genre, I'm not talking about American novels here, I'm saying American in a metaphorical sense: open to immigrants and amateurs. My favorite literature is equally astonishing literary quality and democratic approach.

Would you ever compromise on your books to get more readers?

I would, but I can't. Every time I start something new I say: "This will be easy, this will be easy". And it never turns out that way. My imagination apparently enjoys complexity for complexity's sake. Much of life, by the way, and much of what we admire is intrinsically complex. For a temperament like mine, the hardest job in the world, the most complicated job in the world, is to be simpler. There are writers with a gift for making terribly complicated things simpler. But I know that my gift is the other way around: to take relatively simple things and make them insanely complicated. But here, a person learns who he is, and trying to become something he is not is dangerous.

Do your children enjoy your books?

I have no idea if those bastards read them. I would say they did it secretly as teenagers, but they grew up to be scientists and businessmen. I think they are satisfied that their dad writes things that have some meaning. But did they read them? I do not know. When we finish talking, I have to call them one by one to ask them.

(Glyph editorial office; source: The Paris Review; edited and translated by: Matija Jovandić)

Bonus video: