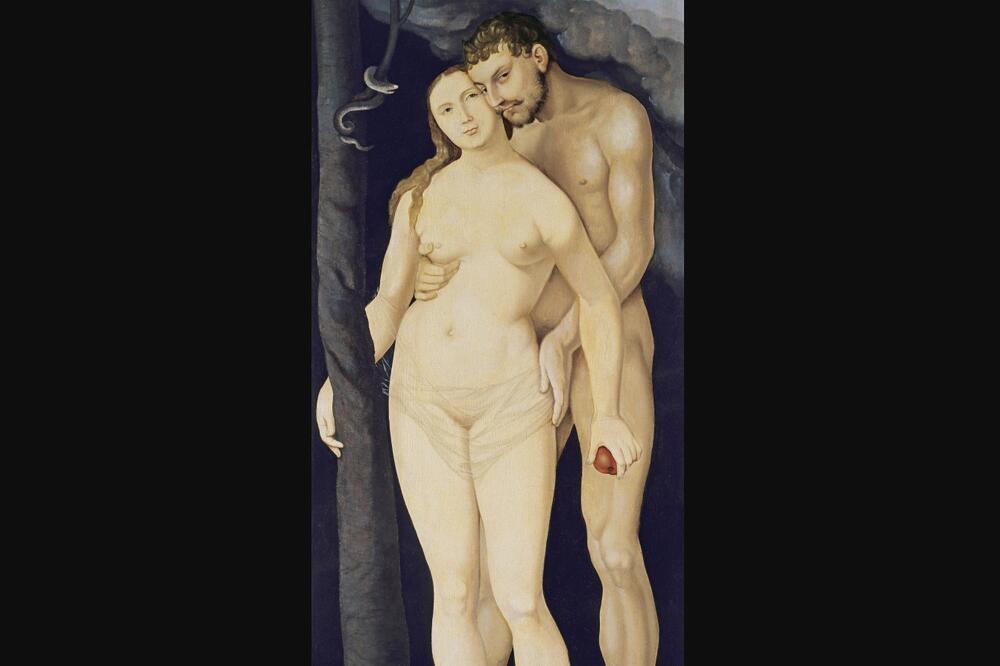

Adam and Eve (1531), on an almost life-size vertical panel, is chronologically the last Baldungova staging of the First Couple. This painting, with reduced use of colors in a space that should be filled with a landscape, again gives, in the final presentation, an abstract character to the whole scene, while only the bodies of Adam and Eve 'glow' in the frame: the narrative context is completely 'darkened', as semantic focusing would be carried out, primarily in the domain of metaphor. As suggested by the transparent veil placed in front of Eve's erogenous zone as a visual lure, the first artificial object is introduced into the natural environment of the Fall, which has no place in the narrative, which aggressively 'falsifies' the biblical text, which is a strong indication that Baldung's mise-en-scène now it primarily functions in the cultural sphere. It is the last stage in the consideration of the (i)story of Adam and Eve: not so much a narrative whose existential consequences are all-encompassing, but a metapoetic essay on how the metaphorical layer of the image functions, how the articulation of symbolic rhetoric, i.e., the rhetoric of symbols, is carried out writing and controlling the sexual connotation, especially when the desire is active - through a complex dialectic of prohibition and freedom - on both sides of the proscenium.

The Fall, in such a way, is a permanent reflection of the human condition through the constant reactualization of original sin (each new story begins with a repetition of the primordial situation), but also an original setting in which the scope of visual language as such is questioned: for Baldung, the order established by the interaction between Adam and Eve is a key spatio-temporal constellation where the author, after all, always elaborates his own painting, its visual profile and referential origin. It is a primal image ultimate in which the bearing (that is, pregnant!) issue of identity is dramatized: the painter (and, of course, the viewer) should recognize themselves in the scene, but this kind of visual construction eminently serves to recognize the author's presence in a different arrangement and placement of the familiar material. Just like the fallen figures, Adam and Eve are the ideal mechanism for activating the dialectic of gaze embodied by painting, where not only does the viewer look at the picture, but the picture also looks back, therefore, looks at the viewer himself, in opening and revealing the authentic mise-en-abîme the dimensions of the scene as it meets the eye.

On Adam and Eve, two naked bodies are placed against a dark, more precisely obscure background that seems to erase secondary details from the traditional narrative. The tree of knowledge is black, the trunk as if burned in some undeclared fire, without leaves (perhaps that is exactly why Baldung, in turn, provided an artificial, delicate, transparent veil 'from the outside'), without vitality and attraction: without Eve's right hand, as a contrast , it would almost completely disappear from the picture, "drowning" into the background darkness. The red apple is "extreme", its importance is only marginal, and in this respect it is interesting and indicative in many ways to compare Baldung's approach, as an author who is too often accused in criticism of unrestrained misogyny and whose iconography of the Fall is more openly eroticized, with that of his contemporary ( and according to some information, also the trainees Durer's workshops), Lucas Cranach the Elder who in his versions of the story of the First Parents, and unequivocally in Adam and Eve (1508-10) and Adam and Eve (1526), persistently shifts the blame to Eve, who gives Adam an already bitten apple, while Adam, in the second picture, is stupidly scratching himself on the head, debating whether to accept the gift that will lead to expulsion from Paradise. The snake, which in Baldung's earlier paintings was known to grow to monstrous proportions (which was proportional to its influence in a story that would have monstrous consequences), is here hopelessly tiny and thus harmless, devoid of diabolical agency and aggressive intent, and the author will achieve its potent and potential phallic function by other means.

In fact, the snake would completely disappear from the picture if some light from the clouds did not come from the upper right corner of the picture, but Baldung does not specify whether it is the first rays of the morning or the last glimmer of dusk. (Is, with a touch of irony, the painter here anticipating the magic hour?) What this certainly signifies, however, is that Adam and Eve, through the cycle of night and day, entered a kind of rut after the catastrophe had already occurred. From the stormy, heightened melodrama of the Fall, ontological corruption, Adam and Eve enter the 'everyday' in which their relationship will be - primarily sexual, and the main purpose reproductive, in the reproduction of God's image by which man is 'drawn' or 'painted'. That is why, in the new (de)marking of male and female being after their degradation, in the newly established epistemology where the metaphysical situation can be processed terminologically and with a secular vocabulary, Baldung focuses on the bodies of Adam and Eve, more precisely on the examination of how the body trope becomes an asset (Stephane Mallarme would say: 'demon') analogies: anthropological knowledge.

Although she clings to the tree with her right hand and holds a red apple with her left, it seems that the golden-haired Eve, who is absent-mindedly looking into the distance, may have been blinded by the coming pleasure or already introduced anxiety, but support is given by Adam, who seems to be adjusting her body for the best visor. What the gaze concentrates on is located, in the same line, exactly between her two hands and the two objects, the tree and the apple, that 'ground' her: a transparent 'gauze' that revealingly hides her genitalia and pubic hair. In order for the scene to turn out to be erotic, it is necessary to have a veil in the organization of the spectacle, an 'excess' that evokes a 'deficiency', a kind of prohibition or membrane that additionally indicates what must not be represented. If the Northern Renaissance, with to Van Eyck the inaugural brilliant technique that can meticulously depict all the nuances of reality, defines painting as a 'window to the world', a specially chosen point that allows us to see what comes from reality with a special, life-giving precision, magnified to a degree that includes a new layer of knowledge that is exclusively rendered in the visual domain, then Baldung profiles his version of painting as a transparent veil thrown over the world which, in that perspective, is established as erotically constituted. The gaze that encounters the obstacle becomes aware of itself, of its range, of its limitation, of the desire that motivates it, and of the pleasure that, once the scene is enunciated from a voyeuristic position, arises as a result of greater concentration and greater desire. Only with the help of a transparent drapery that indexes where the center of interest really is in the entire show, mise-en-scène can become metapoetically grounded: Baldung's providence. The newly found sexuality, due to the necessity of incorporating the Law, must partially be a blind spot in the author's visual regime, but that is why the trope is permanently freed: the symbolic order always rests on a prohibition that is overcome only by the increased activity of the signifier, which prepares the ground for the triumphant supremacy of fetishistic aesthetics.

A fetish is what makes the invisible or imaginary visible: the gaze that penetrates or penetrates through the veil, from a voyeuristic distance. With the help of the veil, Baldung organizes the viewer's attention or focus, which naturally turns towards that part of the picture that is double-marked, which is the least 'clear', which offers a certain resistance to the viewer, which always already places the desired object as a kind of stain. The veil functions as a (cinematic) screen: an eminent space for projection. In the Northern Renaissance, transparent veils were an opportunity for painters to show their skill in describing transparent things (and again, the examples of Cranach the Elder in his works with the figures of Venus, Lucrezia and the Graces are especially striking), but with Baldung this inscription of a kind of vacuum, indicating a void , emphasizing the permeable whiteness, is essentially a meta-procedure that, in libidinal design, frames the image in a different way, more precisely, according to a new imperative, it produces an image within an image within the already established Fanaik's 'ocular revolution'. The picture within the picture means that, within the existing frame, a territory has been found that escapes, as a piece of the Real, conventional description: that marked area is - the enigma of female sexuality and female pleasure, and that is precisely at the work where the control is literally in the hands of Adam which set Eve up for her final pose.

Bonus video: