It was not a warm welcome for the glamorously dressed guests arriving at the film festival in Caceres. "No to the mine! Yes to life!", "Cáceres is not for sale!", "Shame!" - chanted several hundred demonstrators along the street leading to the Great Theater. And what does the local film festival have to do with the mine?

It is about the sponsor, Extremadura New Energies, a company that plans to produce 26 tons of lithium hydroxide over the next 467.000 years. The ore should be mined only a few kilometers from the Great Theater.

The company hopes that such gestures, funded by its foundation, will convince the local community of its honorable intentions. Anti-lithium mining activists from the "Save the Cáceres Mountains" platform see it as a cheap trick.

Cáceres is a sleepy town of 100.000 inhabitants, popular among tourists for its UNESCO-protected old town. It is located in rural and often neglected Extremadura, the poorest region of Spain, on the border with Portugal.

Some six years ago, Casares joined a growing list of places in Europe that have found themselves in a geopolitically colored race for resources.

The race for "white gold" in Europe

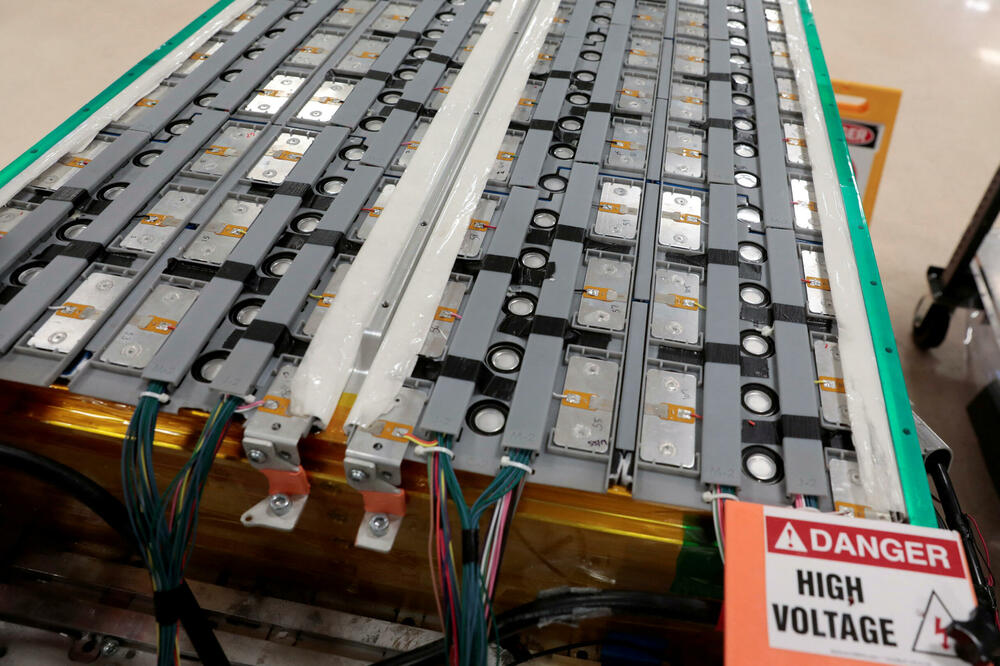

Lithium is a metal used in high-performance batteries, key to carbon-reducing technologies such as solar panels and electric vehicles, plus smartphones and laptops.

Australia, Chile and China are the world's largest producers with a 90 percent market share, according to data from the World Economic Forum. Lithium mining, particularly in South American salt lakes, has been linked to environmental destruction, water shortages and – in Bolivia – violent political backlash.

In recent years, the EU has taken steps to free itself from dependence on imports of so-called critical raw materials needed for the technology of the future, in part by increasing the exploitation of domestic raw materials such as lithium.

For and against the mine in Caceres

Montanja Chaves, the spokeswoman for the protest organizers, says that they are "very concerned" about the new EU plan.

Activists worry about a myriad of things: pressure on local water supplies - no rivers flow through Cáceres - air pollution from increased road traffic, contamination of water and land from chemicals used in mining and refining, dust, noise, and even the potential soil destabilization using explosives.

The Sierra de la Mosca mountain, located between the city and the future mine, is of great importance to Chávez. Like many women in the area, she too was named after that mountain, more precisely after the patroness of Cáceres, the Virgin of the Mountain.

"I've had a strong connection with this area since I was little," she told DW, which is why she and other locals have been fighting the mine for years.

However, it seems that not everyone thinks the same. "It's fantastic," 76-year-old Jose-Antonio, a retired agronomist, said of the future mine. "Cáceres is a city of retirees, nothing else". He believes that the city needs jobs.

Walking along the winding shopping street was Ugo Galjeano, a 23-year-old tourism student. He sees things similarly: "There is no industry here. Only tourism is not enough, the city needs an economic engine".

Demand for lithium in the EU is largely driven by the automotive industry. This sector accounts for seven percent of economic output, and the EU plans to phase out the sale of new cars with internal combustion engines by 2035 as part of a broader 2050 plan.

Lithium mine, second round

Given the political and economic importance of those projects, one might think that activists against the mines in Cáceres don't stand a chance. But in 2017, they already won a victory by mobilizing the city's population against the original plans for the mine.

Since the local government also objected, Extremadura New Energies had to create a new project and now the plan is to do so – an underground mine with additional facilities and facilities nearby.

Mayor Luis Salaja of the center-left Socialist Party opposed the original plan, but is more open to the new proposal, which was officially submitted late last year and is still being considered by local authorities.

Ramon Jimenez, director of Extremadura New Energies, believes the mood in Cáceres has now changed:

"When I explained that the mine is underground, that we will not use sulfuric acid or natural gas, that we will heat the process using green hydrogen that we will obtain from solar energy, that we will use water from the sewage treatment plant - people understood that the impact on the environment minimized and saw the possible benefits," he told DW.

The mine should create several hundred long-term jobs, and fill state coffers with tax revenue, Jimenez said.

He claims that lithium has to be exploited somewhere, so it is better to do it in the EU, where there are stricter environmental protection laws. Refined lithium would be sold to car companies in Spain and the EU, rather than coming from China.

Mining companies "usually have their way"

Gavin Mudd, a professor of environmental engineering at RMIT University in Australia, believes there is much uncertainty about the long-term impact of lithium mining.

In theory, what Extremadura New Energies promises is technically possible, but there are also many dangers mentioned by activists. Ultimately, it depends on the particular mine, Mad said.

The mining industry in Spain has a bad reputation, and rightfully so, he noted, pointing to pollution in the southwest of the country.

"Mining companies are not used to being told what they can and can't do. They usually do what they want," Mad said, adding that local communities should be able to say "no" to the mine, but it is successful. resistance rare.

In Serbia and Portugal, the resistance was successful

One of those rare examples is the Jadra valley in Serbia, where the largest lithium mine in Europe was to be built. But Anglo-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto was denied an adapted spatial plan last year due to public outcry. Whether that decision is final remains to be seen.

Plans for the Mina do Barroso mine in northern Portugal have also met with fierce opposition.

The director of Extremadura New Energies Ramon Jimenez is confident that Cáceres will approve the mine and that it will start working as early as next year.

That company has already cast its eye on other potential locations - which are "ecologically and economically sustainable".

"Some are in Spain, some in Europe, some in Australia," he said, without revealing where he expects his firm to exploit the "white gold."

Regardless of whether Cáceres ends up with a mine, demand for lithium is unlikely to disappear anytime soon. The European Commission has estimated that up to 2030 times more lithium than now will be needed by 18, and even 2050 times more by 60 – for the EU to meet its climate goals.

Bonus video: