Preparation for going to Aleksinac included flipping through the novel "Anna Karenina", which I devoured in my high school days, and then left it gathering dust for a long time. I came across a place where a member of the Petrograd elite, Count Alexei Kirillovich Vronsky, explains his decision to go as a volunteer for Serbia: "As a man - said Vronsky - I am good in that life is worth nothing to me." And that I have enough physical energy to break into an infantry machine with a sword and crush everything around me or die - that's what I know. I am glad that there is something for which I can give my life, which I not only do not need, but also hate. It will come in handy for someone”.

Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy wrote to Anna Karenina between 1873 and 1878. Serbia under Prince Milan in alliance with Montenegro under Prince Nikola declared war on Turkey in 1876. The commander-in-chief of the Serbian army was Russian General Chernyaev. And Russia declared war on Turkey in 1877. These events ended with the famous Berlin Congress in 1878, when Serbia and Montenegro were recognized as independent states.

For Tolstoy, these events served as historical backdrops for the drama of Vronsky, who goes to war because his lover Anna Karenina - killed herself. Allegedly, behind the character of Vronsky there was a real man - Nikolai Nikolayevich Rajevsky who fell in battle with the Ottoman army near Aleksinac.

From Gornji Adrovac to Hollywood

Sunny day and almost no one on the highway, turning towards Aleksinac behind Nis. We continue past Aleksinac towards the hill. We climb the asphalt with a car that is cracked like the crust of a burnt pie. After half an hour, we pass through the village, which history only put on the world map once - when a Russian colonel died there. Below, along Moravica near Aleksinac, there is little snow. Up here he lingered on the hillsides and slopes.

Russian colonel Rajevski was killed near the village of Gornji Adrovac in August 1876. At the place of his death, since 1903, there has been a "colorful church" or "Russian church" as the people call it.

When one sees the church, one cannot escape the impression that it has descended there from some other dimension. The architectural style and approach are different compared to other religious buildings in Serbia. The line of linden trees, for which, according to tradition, seedlings were brought from the Ukrainian estate of Colonel Rajevsky, underlines the feeling of loneliness that inevitably overwhelms rare visitors. Or is it just the melancholy of a bright January day? In front of the church is a monument to Russian volunteers who died for the liberation of Serbia. It is more recent, while the stone cross on which the name of the Russian colonel is written is quite old.

It was not only the war of 1876 that left its mark on the church. On the walls of the church are plaques with the names of local people who died during the Bulgarian occupation. I'm almost convinced that the church is closed, yet I grasp the doorknob with some hope. Open. I enter a space of absolute silence. My attention is drawn to the painted figure - Nikolai Nikolayevich Rajevsky.

At the moment of his death, he could not have known that his death would serve as a guide for Tolstoy for the fate of his literary character Vronsky. And Tolstoy had no idea that Anna Karenina and Count Vronsky would make it to Hollywood - and that in a series of film adaptations they would speak English with an American accent.

We descend from the village down a winding road, heading towards Aleksinac. As soon as you pass the concrete building of the bus station in Aleksinac and the city park with a monument from the Tito era on the right, you come across the bridge over the Moravica. From there you can go on a tour on foot.

The town was founded not far from the place where Moravica flows into South Morava. Although there are traces of the settlement dating back to the Roman era, chroniclers say that it was first mentioned by its name Aleksinac in Turkish sources in 1516. And the legend about the name goes like this: Every day a hajduk called Usein-aga from the forest. But hire someone for Aleksa to catch his thief. When Aleksa does that, the hajduk ends up on the hook, and Aleksa is repaid with the estate on the site of today's town. Aleksinac, therefore, in that story was named after Aleksa, a bounty hunter for the Turkish account. In fact, almost everything worth seeing in the town is located along Ulica Knjaza Miloša. The pedestrian zone is almost empty.

It is written that the Serbian prince Miloš Obrenović understood the strategic importance of Aleksinac: "I am determined, God willing, to build two gates in Serbia - one in Belgrade towards Ćesarska (Austria), and the other in Aleksinac towards Turkey". This southern gate was designed by Austrian architect Franz Janke on the duke's order. In the structure of the city, the Central European urbanist handwriting is legible.

The Church of St. Nicholas is at the end of the pedestrian zone. It was built in 1837 in a place that the people called Agina's threshing floor. Only a few years after liberation from Turkish rule, Prince Miloš sponsored the name of the church, since it was the baptismal glory of Obrenović.

We enter the church, which is heated - the baptism is in progress. An elderly man fell ill. His people gathered around him. On the way out of the church, we can already hear the siren of an ambulance. I guess Nicholas the Wonderworker will also help.

Near the church are all representative buildings in the town. I am particularly interested in one of them.

A personal Aleksinic story

In June 1952, twenty-year-old Mara Bunić took the final exam at the Teachers' School in Aleksinac. Her young biography has already been broken by the great hammer of the epoch. Born in the house of an officer, veterinarian of the royal stables, in Zagreb, she followed her father's service from Maribor, via Niš and Ćuprija. And then came the war in which he lost his parents. He spends a year in a home in Vidin, Bulgaria - Yugoslav educators and orphans were given a building there until the destroyed schools and homes in the country are repaired. Then he moved to Belgrade, to a home in Krunska. Finally, he arrived in Aleksinac and studied there until the summer of 1952.

At that time, I must not have thought about the future teacher who eleven years later would become my mother. She has been gone for seven years now.

That is the real reason for coming to this region. The building of the Basic Court significantly determined the mother's resume.

The Teachers' School was transferred to Aleksinac from Belgrade in 1896. For these purposes, a representative building was built in which the school worked until March 1963, when the judiciary removed the school from the building. One thing is certain - my mother, then a girl with her dreams and hopes, has been entering the door in front of me for years.

I remember that she once told me how the boys were rudely throwing things at her and her friends on the Aleksinac Korza - one of the ordinary male rudeness that a child from the upper middle class, stuck in the young Palanac socialism, never got used to.

Diploma from the sunken world

In the papers she left behind, she left the diploma of the Teacher Training School from Aleksinac. Now I read more from it than just grades. Mara Bunić was a very good student. A series of fours from natural history through the basics of philosophy to pre-military training. A few triples - mathematics or Russian. A child who probably started learning French in better pre-war schools, studied German in occupied Serbia, and Russian in liberated Serbia. The only clear A on the testimony was the governance.

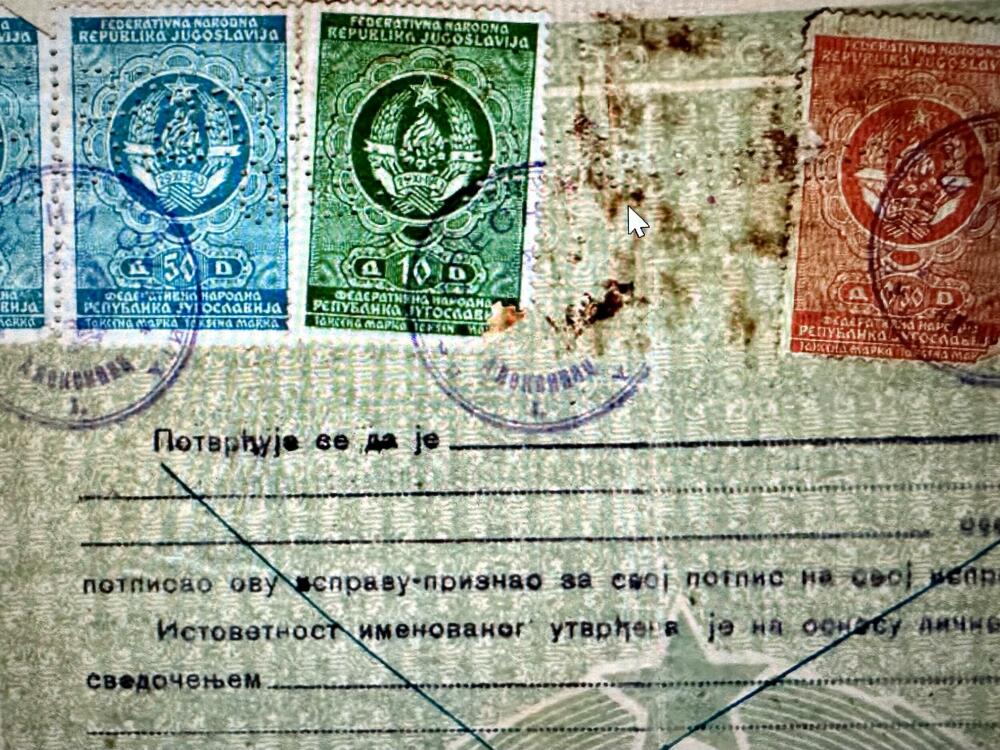

The tax stamps were a story in themselves. The coat of arms of the Federative People's Republic of Yugoslavia - with five torches - was located on a background of kerosene, light lipstick or green color. The torches then symbolized nations, and only with the later constitutional development - republics. Two stamps of fifty dinars each, then one of 30 and one of ten. Above all that, the seal of the District Court of Aleksinac, People's Republic of Serbia.

The diploma form was called Form III/3, it cost two dinars per tab, and it was printed by the Invalid Bookstore of Serbia from Belgrade.

The whole sunken world stood on this paper.

This morning I woke up and said - let's go to Aleksinac. More than once I intended to visit this town, where my mother was a resident exactly 72 years ago. It seems that this Sunday in January had to come, for me to finally find myself in a place that is silent about so many past lives.

Southern food

Once we are in the town, which clearly belongs to the Serbian south - it is only thirty kilometers from Niš - we will refresh ourselves in a tavern. One of the famous ones is "Medalja", not even two hundred steps from the main street. I will skip everything that they put on our table in a pleasant atmosphere - I can only say that "Medalja" is among the excellent taverns from Niš to Vranje, from Pirot to Prokuplje.

The waiter is talkative, he worked in Montenegro with an excellent chef, Leskovčanin, he doesn't know how long the boss will keep pushing, because the pubs on the outskirts are safe from city drunkards, and the center doesn't know how to defend against them. We are rooting for "Medalja" - to remain a place where families go for lunch on Sundays.

A toast to Kosara

I remember that the poet Velimir Rajić was born in Aleksinac in 1879. His most famous poem "On the day of her wedding" echoes with southern mourning:

And my beautiful dreams collapsed,

for your head is now covered with a crown,

next to you another stands before the altar -

may my love be alive!

It was recorded that her name was Kosara. The black-haired beauty married on the second of October 1903 in Belgrade. The poet immortalized the unattainable sweetheart that same evening in verses that were later recited by generations of actors and rejected lovers.

Those verses were sung by Zvonko Bogdan in 1971.

I order another one and toast the poet, the great-granddaughter of the famous Serbian insurgent Tanasko Rajić. I drink to the souls of all the miners from Aleksinac who died.

Cheers to Mari Bunić, to her Aleksinic dreams, to that man struggling for breath in the church, to Colonel Rajevsky, Count Tolstoy and Count Vronsky, his Anna and all the unhappy loves of the world. Of course - I also toast my companion who agreed to come with me to Aleksinac today as if it were Monaco.

Bonus video: