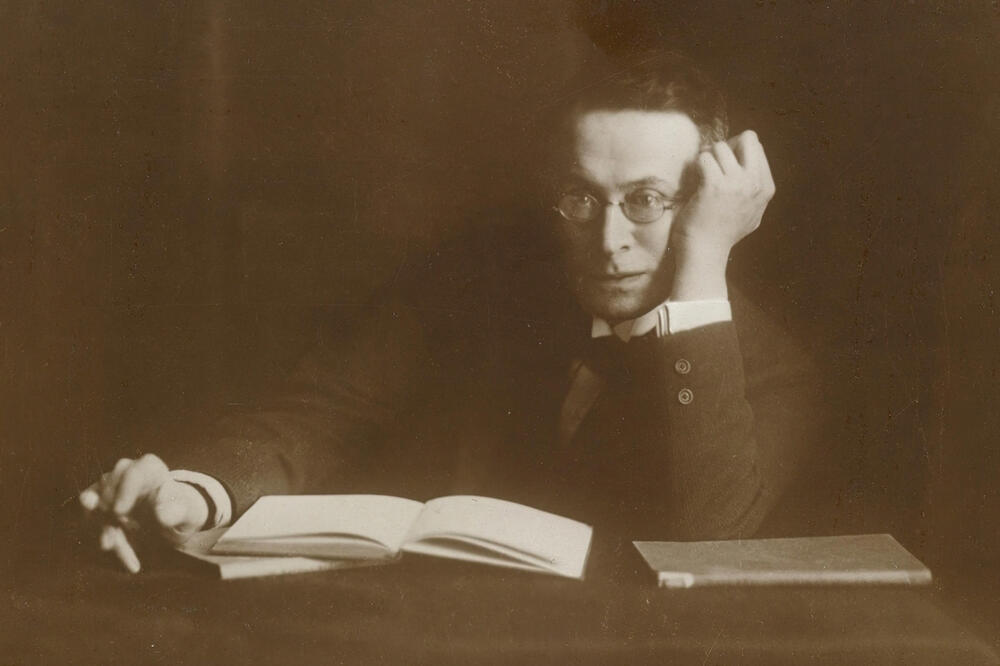

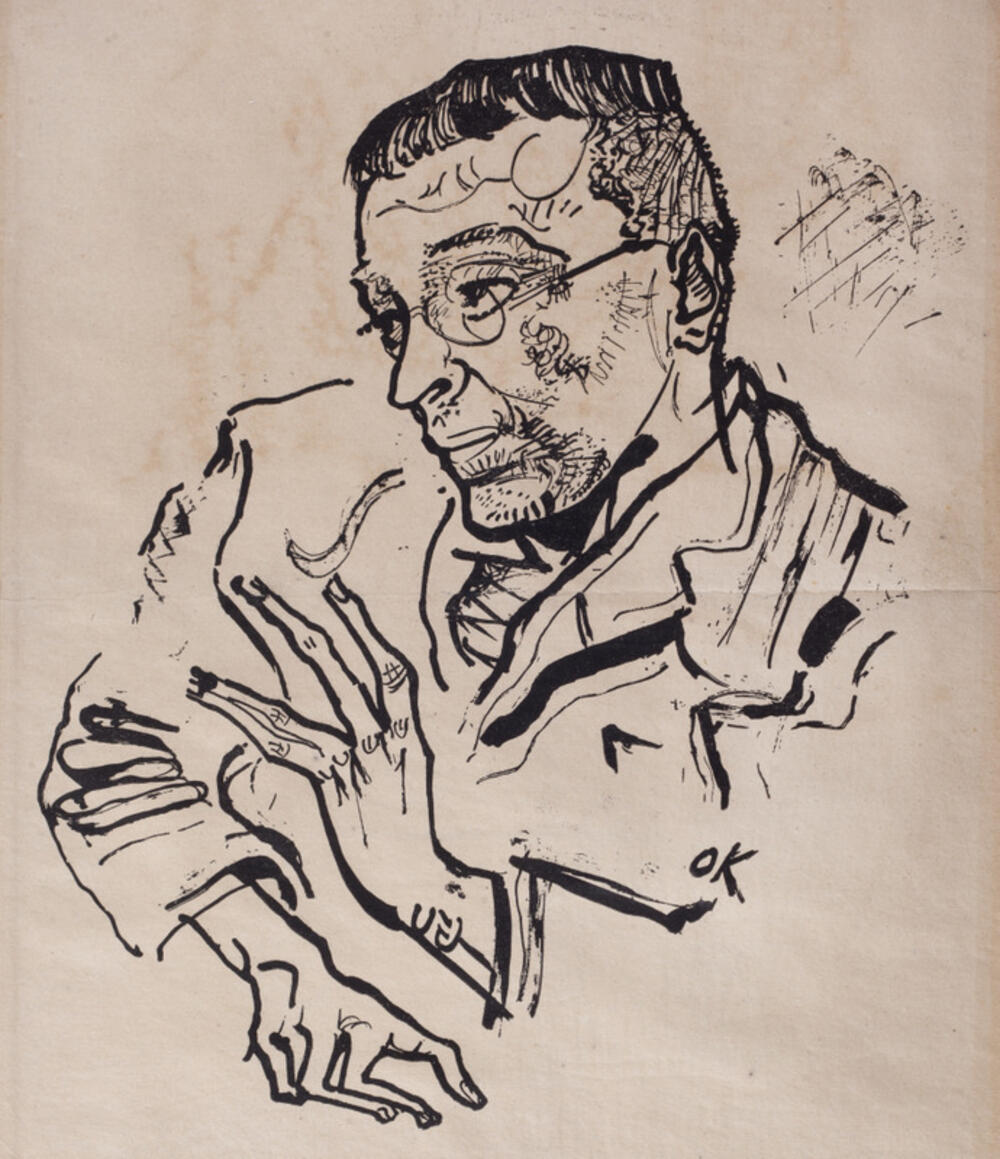

There are few figures from the first half of the last century who permeated Vienna with their activities and legacy like Karl Kraus. In the gallery of famous fellow citizens - from Sigmund Freud to Ludwig Wittgenstein, Gustav Mahler to Robert Musil and Oskar Kokoska, to name just a few - he was probably the phenomenon that attracted the most admirers and haters at the same time.

Moreover, the famous Viennese was not born in Vienna at all.

Bismarck's headboard

He was born in the present-day Czech town of Jičín, about eighty kilometers north of Prague, in the historical province of Bohemia. Varoš had a glorious history. During the Thirty Years' War in the 17th century, it was the capital of the duchy of the Catholic general Wallenstein. In the middle of the town is his palace. Once again, great history knocked on Jičin's door when he found himself in the vortex of the Austro-Prussian War. About forty kilometers from Jičín, near the present-day Czech city of Hradec Kralova, then Königrec, in July 1866, Prussia defeated Austria militarily and assumed primacy in the German lands. Prussian Chancellor Bismarck spent the night in Jičín, on the main square, in the house of the rich Jewish merchant Jakob Kraus and his wife Ernestina.

Less than eight years later, on April 28, 1874, Karl Kraus was born in that rich house. Family tradition says that he was born in the room where Bismarck died. Perhaps this is the reason why Karl Kraus was delighted with the German chancellor all his life: "As a man of genius, as a servant of the state only talented", he wrote about him. He was happy to read Bismarck's book of memories again and again.

However, the family is moving to Vienna with their three-year-old son Karl Kraus, so the town of Jičin will remain a part of the Kraus family's memories. The Viennese environment will become decisive for the linguistically gifted boy.

Vienna as a world

As the ninth child in a row, Karl Kraus couldn't really be lonely. He graduated in 1892, entered the Faculty of Law. At the same time, he began writing theater and literary reviews for German-speaking newspapers. For some time he tries his hand as an actor, without much success. He left law in 1896 and devoted himself to the study of philosophy and German studies. He did not finish that study either. In 1897, he published his reckoning with the literature of Viennese taverns and modernity, "Demolished Literature". The satirical book brought him great success with the public and lasting enmity in some Viennese literary circles.

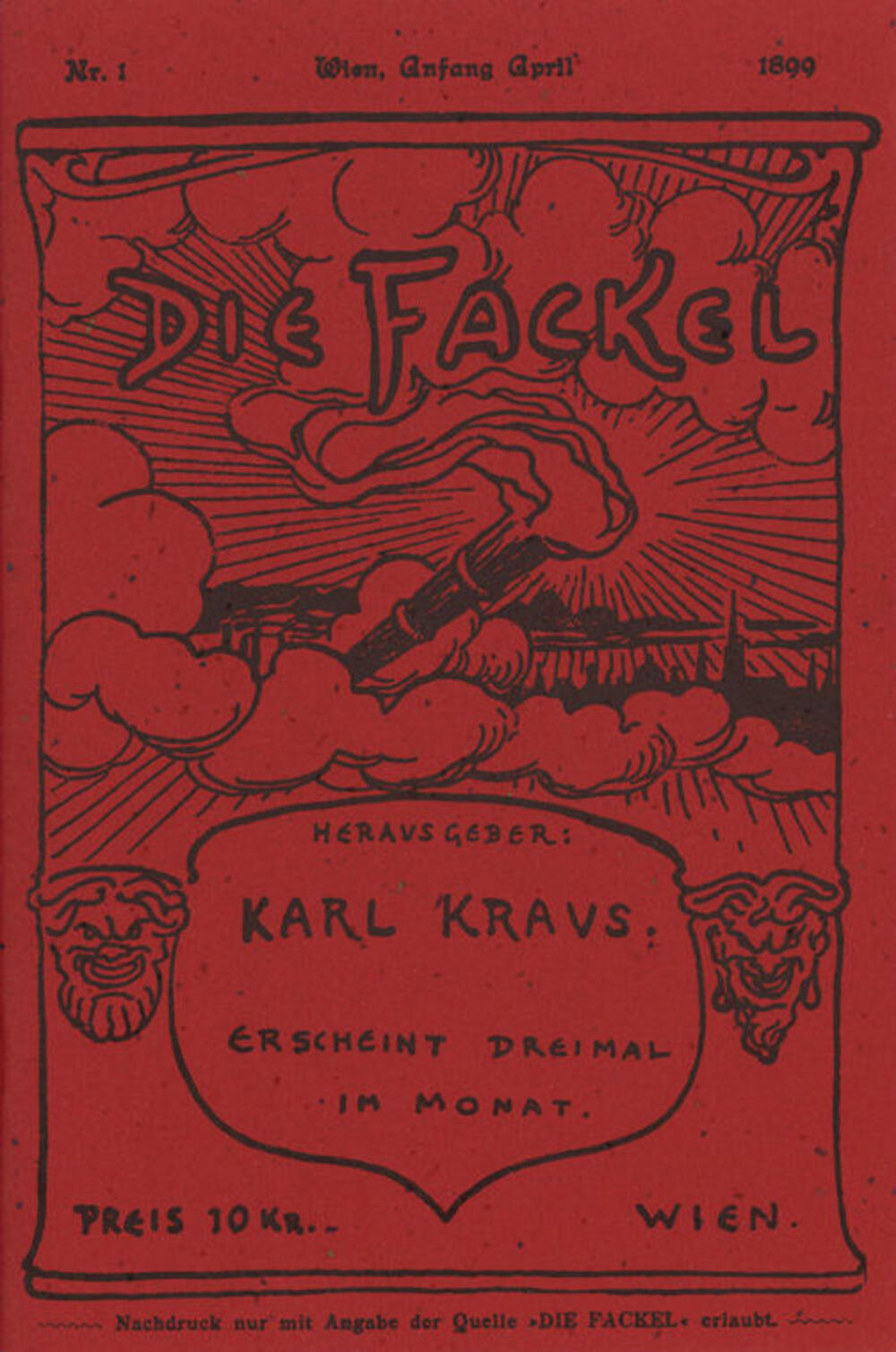

This was followed by the founding of the satirical magazine "Die Fackel" (Torch). In the same 1899, he resigned from the Jewish religious community. In his magazine, which achieves unprecedented success, he publishes shrewd aphorisms about the prevailing sexual morality. "The scandal begins when the police end it," he wrote about it. He wrote the largest number of articles in the magazine himself. Since 1912, he has not published other people's texts. Already the first issue reached a circulation of 30.000 copies.

He spared neither bad journalistic language nor his literary contemporaries. He became one of the biggest fighters against the decline of the German language. "The thing started to rot from the tongue. Time stinks since the phrase". He mostly applied the debunking of linguistic inaccuracy, phrasing, cheap reaching for effects in the articles of the daily newspaper "Neue freie Presse" (New Free Press).

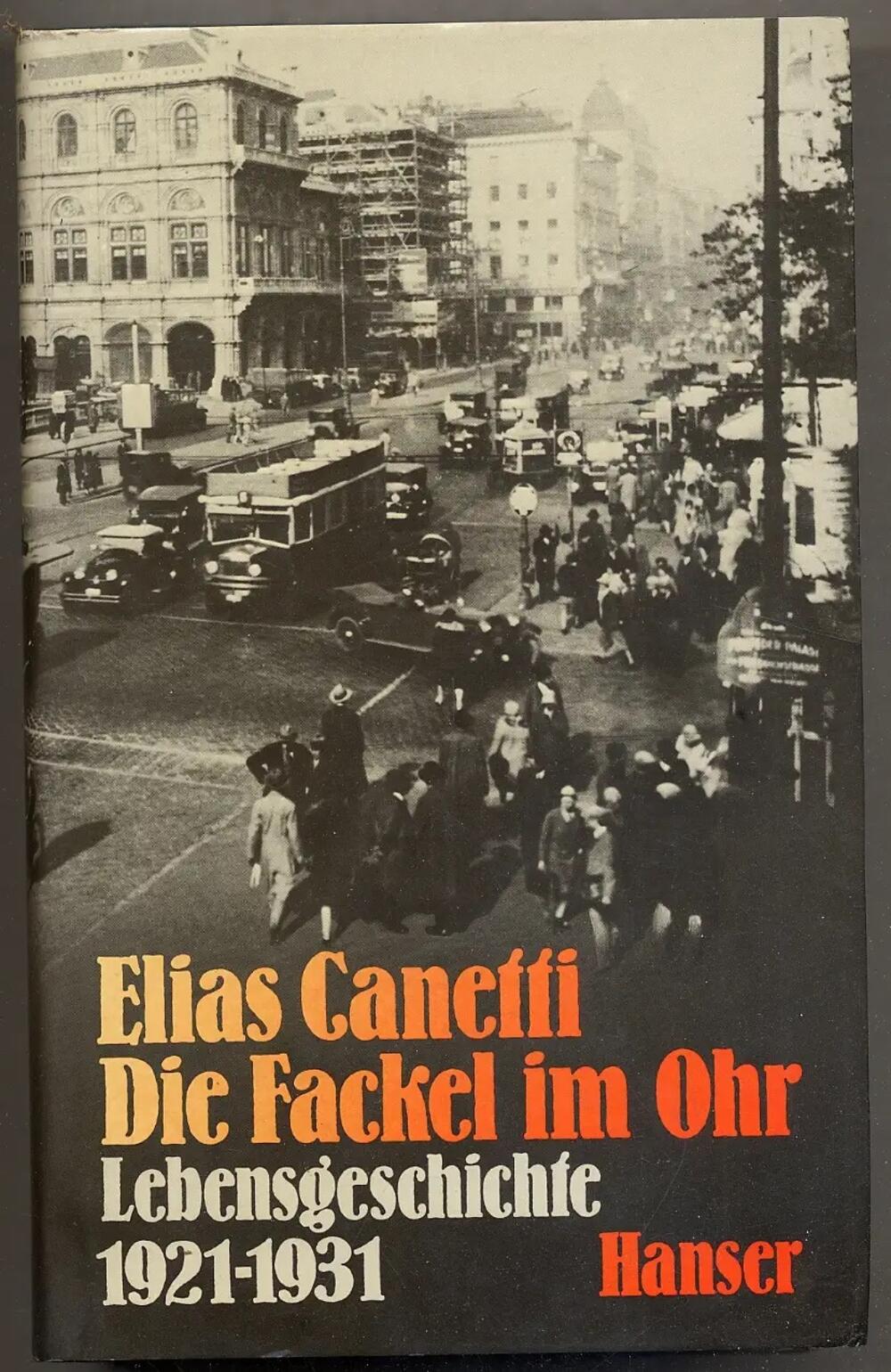

Already in 1910, he held his first public reading, which became a first-class cultural event in Vienna. By 1936 he had 700 such readings. In the book "Torch in the Ear", Nobel laureate Elias Canetti testified about the impression Karl Kraus had on the audience: "They say he is the strictest and greatest man living in Vienna today." No one finds mercy in his eyes. In his lectures, he attacks everything that is bad and corrupt... Every word, every syllable in 'Baklja' is his. He accuses and judges. There is no defense, it is superfluous, because he is so just, that he does not accuse anyone who does not deserve it. He's not wrong, he can't be wrong... When he reads from that (from The Last Days of Mankind), they say that people are like paralyzed. Everyone in the hall is motionless, they hardly dare to breathe... They say, whoever heard him, doesn't want to go to the theater anymore, because it is boring compared to him, he himself is the theater, but better, and that wonder of the world, that the monster, that genius, bears the extremely ordinary name of Karl Kraus".

Contradictions

Of course, this phenomenon generated a lot of enemies. Among journalists, writers, but also in the government hierarchy. Court trials made him more and more popular. The material from those processes would later appear in his magazine. Playwright and writer Artur Schnitzler stated that Karl Kraus had a "cloud of hatred". Kafka's friend, the writer Max Brod, wrote about him that he is "an average mind, whose style rarely avoids the two worst halves of literature, pathos and superficial jokes."

Karl Kraus was baptized in the Catholic Church in 1911, but left it in 1922. Although he came from a wealthy Jewish family, his attitude towards the "Jewish question" was contradictory. He considered Zionism wrong in relation to the possibility of assimilation into the great Central European culture. He despised the dominance of the market and profit, his criticism of the insatiability of modern man sometimes used anti-Semitic prejudices. Some critics see in such actions of his "Jewish self-denial", in today's language of the right - "autochauvinism". Still others present evidence that exaggeration is at the very core of his literary process.

A conservative defender of the good German language, he became a pacifist during the war. First, he harshly attacked the "enemy within" - all those who made money from the war, the loose patriotic press, the Black Bersians, all those for whom war is a brother. But by the summer of 1917, he excluded honorable officers and the military elite from his criticism. Then he realized that he had to say B, when he had already said A. He deals head-on with all the "pillars of society" that led to the disaster. The "traitors of humanity" became the church, the army, high politics: "How do they rule the world and lead it to war? Diplomats lie to journalists and believe it when they read it".

The last days of mankind

From 1915 to 1922, his main work, "The Last Days of Mankind", was created. "The performance of the play, the scope of which would require about ten evenings according to earthly criteria, was conceived for the Martian Theater," says the introduction. And indeed, rarely has any work so comprehensively responded to the madness of the First World War. Already at the beginning, the colporteur on the streets of Vienna exclaims: "Special edition! Noje fraje presse! Bloody act of Sarajevo. The perpetrator is a Serb!" From the eve of the war through its beginning and course, we follow an incredible gallery of characters.

"We will smash the Russians and Serbs to pieces," the mob chants. It rhymes in German the same way as "Serbs on the willows". The man from Vienna, who is giving a speech in front of a park bench, has problems with the words collected in the newspaper. Semi-educated, he confuses the concepts of defensive war and redistributive war. Austria will rise from the world conflagration as a "phalanx", not as a Phoenix. Then follows the famous part of the speech: "The cause for which we started is just, there is no messing around, that's why I tell you: Serbia must die!" While everyone approves, a voice is heard that gives everything an ironic note: "Everyone must die."

While the mob destroys the shop of a hairdresser who has a "Serbian name", Viennese historians walking around the city talk about the fact that the primitive and violent patriotism of the French and English in the "old German state of Habsburg" is impossible.

The part that Karl Kraus moves to conquered Belgrade is certainly interesting. Šalek, a correspondent for the Viennese daily newspaper, arrives in the occupied Serbian capital and says: "The hopelessness of such places is so great that one cannot even think of taking photographs." What keeps eating at me is that the city is not cobbled at all. It is possible that this was helpful in the decision to raze it to the ground".

Since those times, the media has advanced in the speed of transmission of human suffering. But both Šalek and the two reporters trying to extract impressions from the dying soldier in "The Last Days of Mankind" actually became a cynical media paradigm of the era that heralded the Great War.

Karl Kraus also wrote this about journalism: "There is a question full of anxiety, whether journalism, to which the best works are silently thrown as prey, has also spoiled the taste for linguistic art in future times." I think that from the point of view of the third millennium, the answer to the old master is yes.

Austrofascism against Nazism

After the war, Karl Kraus came closer to the Social Democrats. He saw the coming Nazism as a danger. But the moment Hitler comes to power, Karl Kraus decides to keep quiet - much to the dismay of Berltolt Brecht and other German artists concerned. Instead of a violent reaction, the satirist writes a poem: "He shouldn't wonder what I was doing all the time." It begins with the lines: "I remained mute; and I didn't say why". He ended the song with the famous line: "The word fell asleep, when the other world woke up." He later responded to the criticism - that he did not want to endanger the people he cares about.

Nevertheless, all the time he was writing the book "The Third Walpurgis Night", a kind of showdown with the Führer. It was published posthumously in 1952. It begins with a sentence typical of this inveterate skeptic: "I can't think of anything about Hitler," followed by several hundred pages in which he denies himself. A note was also found in the legacy, in which he says that his ill-will became greater than his desire to write something down, and because of that he could not make it productive. It should be noted that his big delusions included the thought that the Austro-fascist dictator Engelbert Dollfus, who came to power in Austria in 1932 through a coup, and who saw Nazis, Democrats and Communists as his opponents, could be a dam against the spillover of Nazism into Austria.

The language that owns us

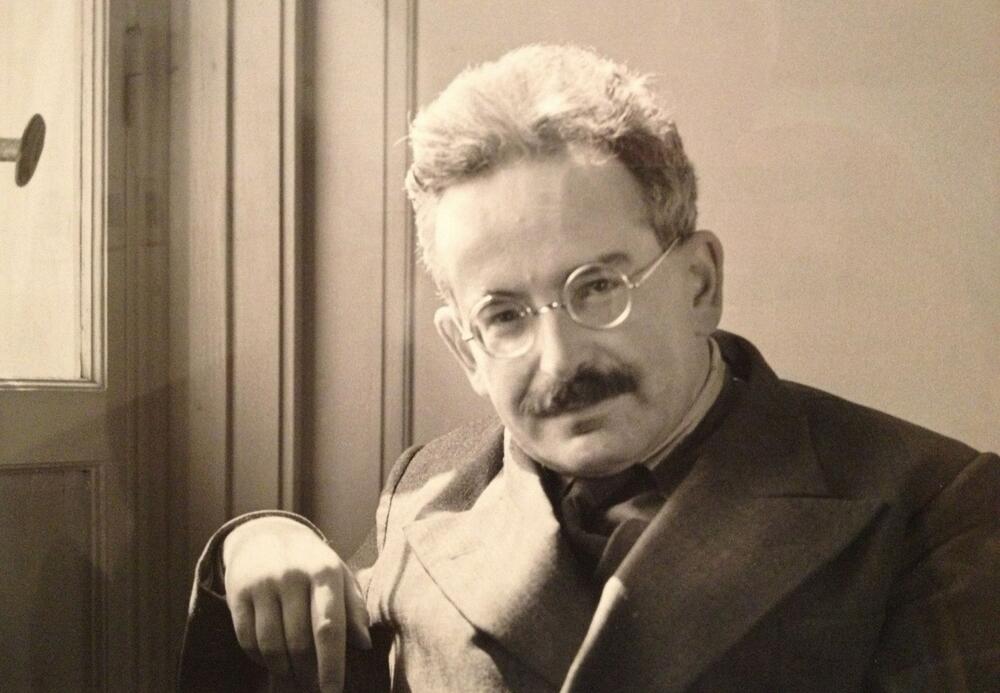

In his 1931 essay on Karl Kraus, the philosopher Walter Benjamin noted the triad - language, justice, politics - on which rested everything Karl Kraus did. Benjamin was an avid reader of Kraus's magazine since 1916. Miroslav Krleža was a "Krausian" in Yugoslavia. And in the Anglo-Saxon area, the extension of his posthumous fame is due to the American writer Jonathan Frenzen, who in 2013 published the "Kraus Project", a book of translations of Karl Kraus's texts with his comments.

What attracted me to Karl Kraus is his attitude towards language: "I don't know the language; he has complete authority over me". For this writer, language acts as a "fork that reveals the source of thought." Such an understanding of language also had practical consequences for his work: "Dilettantes work safely and live contentedly. I often stopped the printing presses and destroyed the already printed, just in the name of one word, which was rejected by the milligram scale of my style."

At the same time, cultivating the language for Kraus was actually saving the world. He rejected violent linguistic innovations: "Only a language that has cancer tends to create new words."

If the translation from German didn't go as I wanted, I would remember this thought: "To translate a work from one language to another means that someone without his own skin crosses the border in order to wear the costume of that country."

Karl Kraus said the following about the linguistic relationship between Austrians and Germans: "I don't like living conditions abroad." I just went there often so that I wouldn't forget the German language". To this must be added the sentence: "The German language is the deepest, the German speech the shallowest".

For a long time, intellectuals, journalists and even Germanists quoted the saying of Karl Kraus, which he never wrote or uttered: "We Austrians differ from Germans in many ways, especially in the same language." In fact, this thought - applicable to the current language situation in the Slovenian south - was expressed by Viennese cabaret artist Karl Farkas, a younger contemporary of the great writer. But in the German-speaking world, almost all sharp remarks about language are happily attributed to Karl Kraus.

April 28 marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Karl Kraus. He has long secured a prominent place in German literary heritage. He is less present in Serbian culture. Although he is the author of perhaps the most poignant poem that speaks in German from the perspective of a Serbian victim. The song is part of the anti-war drama "The Last Days of Mankind". In it, an old Serbian peasant is digging his own grave, awaiting execution, and his children have already been shot by the occupiers. Karl Kraus wrote the poem more than a century ago in the first person singular.

Bonus video: