The fifties and sixties of the last century in SFRY were a time of significant cultural momentum in all arts and culture in general. Serious films are being made, theatrical life received a strong impulse from the new authorities, the biggest musical names on the planet are guests, Yugoslav painters are becoming the stars of the most prestigious exhibitions around the world, and literature, against the background of the so-called breaks with socialist realism, but also the media-attractive polemics between modernists and traditionalists, is also strengthened by the so-called social significance and resonance, but also a space for unprecedented poetic dynamization of the literary scene itself. Numerous and later important literary magazines were founded, as well as literary awards. Among the awards that still have some significance today, NIN's award for the novel of the year, established in 1954, as well as the Njegoš award, which was first awarded in 1963, stand out. deprived of the usual influence of government. It had an aura of "independence", however conditional such a formulation was for the ideological context of the time. It was the first serious Yugoslav award that could go to the hands of even an "unfit" writer.

Which could not be said for the latter. The Njegos award was awarded triennially, with the ambition of being the "Yugoslav Nobel". Such pretensions made this award - totally politically controlled - from the beginning. It is to this fact that Njegoš's award owes some of the biggest controversies that followed it.

Undisputed start

The concept of a three-year award was chosen, and the award is given for a specific literary work. In addition to the monetary amount, the award also brought a non-standard literary honor - the laureate's name will be engraved on a plaque in Njegoševa Billiard. It was an epic bonus on top of the main premium.

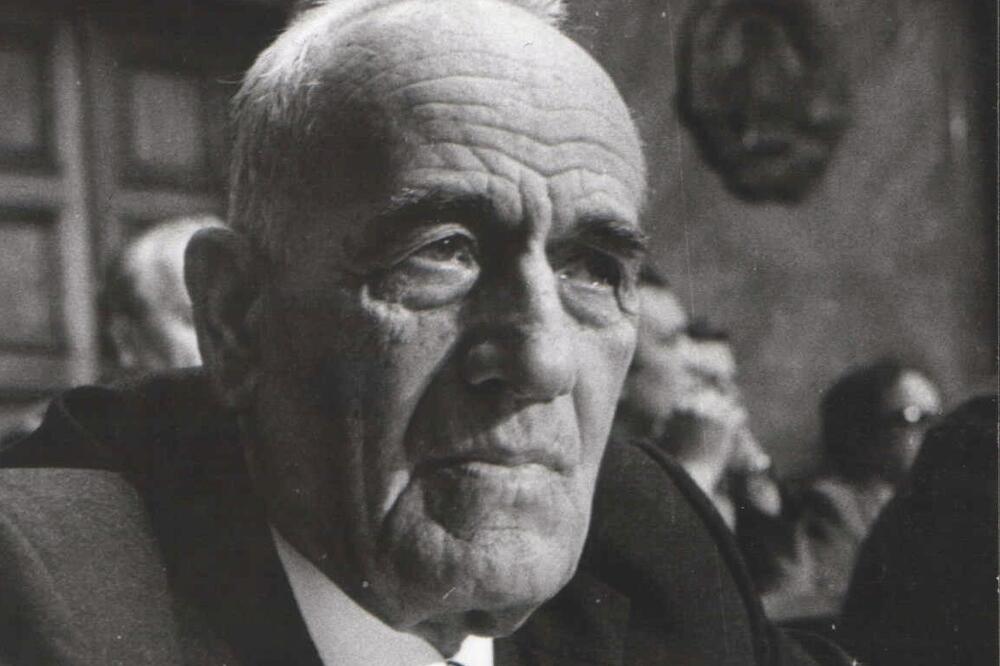

The first three awards were, in one way or another, undisputed. The first decade of this award will be inscribed on a marble slab in the Billiards of Names Mihailo Lalic (1963) Miroslav Krleža (1966) and Meša Selimović (1969). The awarded books were - "Lelejska gora", the monumental "Flags" and the marvelous novel "Dervish and Death".

Mihailo Lalić was a logical choice for the first winner. He wrote a great novel, he was ideologically in agreement with the system, and the domestic public was certainly pleased that the first laureate was a Montenegrin writer.

Later, Lalić would be followed by some typically native misunderstandings, but his literary importance was recognized even by those who did not like his ideological or political views.

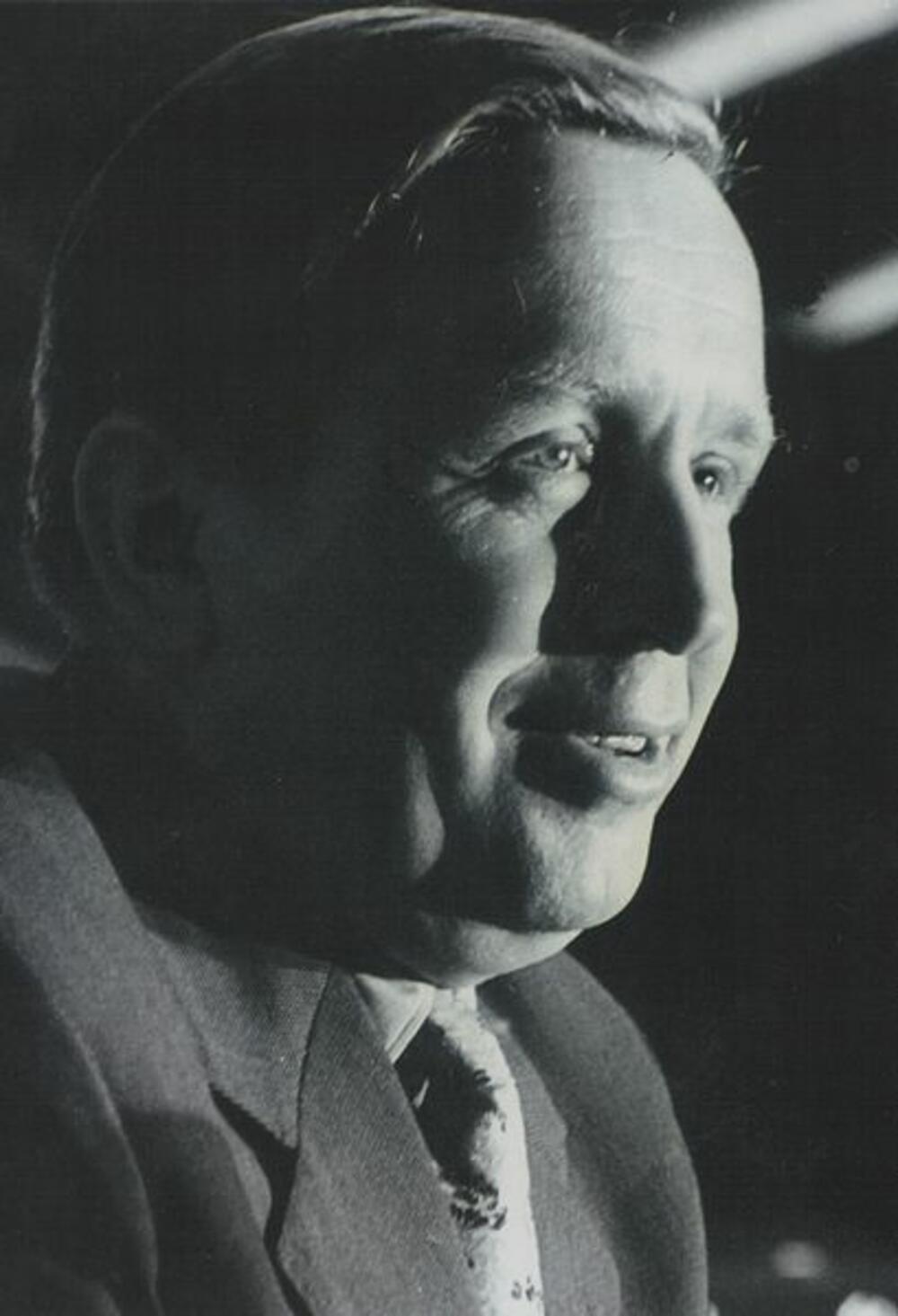

The awarding of Krleža in 1966 emphasized the "Yugoslav dimension" of the award. The tick is, with Andrić i Crnjanski (who came from London earlier that same year) was the biggest name in Yugoslav modern literature, and of those listed, certainly the closest to the ruling communists.

(It was also a time of different journalism. And it would be said that the writers also had more weight. It was rumored that the legendary Bratislav Bato Kokolj, a journalist from Radio Titograd, dragged Krleža through the toilet window of the villa where he was staying, so that he would not have an exclusive statement from the great man. By the way, during his stay in Cetinje and Montenegro, Krleža was impressed by Rijeka Crnojević.)

The next winner, Meša Selimović, has a similar but somewhat different story. Similar, because he too was a partisan and leftist from his youth, but also different because his path of confrontation with ideological power went from family tragedy to personal disappointment. In dealing with political power and its infernal mechanisms, "man is always at a loss". The life and literary path to such an insight made Selimović a great writer.

A literary master who, as critics like to emphasize, matured slowly (like Saramaga), so at an already serious age, and after books that did not necessarily hint at such a breakthrough, he published a novel that included him in the very top of South Slavic literature. "Dervish and Death" was an explosion, a novel that was read, discussed at every turn, an interesting film was made, and it turned its author into an emblematic figure of Yugoslav literature. But also an "oppositional" stance that began to erode the communist apparatus of power in those years.

Although formal for a specific work, it was clear that Njegoš's award was also deserved for his life's oeuvre, literary and "social". The first three awards are indisputable for this reason as well - significant, and in some cases, the best books by great authors were awarded.

The same cannot be said for subsequent awards.

Ocvala phase and controversies

The next award went to the most popular writer of Tito's Yugoslavia - Branko Ćopić. His book "The Garden of Marshmallows" was awarded.

The jury of that year did not have the courage to award the "yesterday" emigrant Miloš Crnjanski for his magnificent "Novel about London".

It is a matrix that will be repeated in several subsequent awards, so the concept of awarding a specific book has been suppressed in the name of the importance that the writer has earned with some other books. And the principle of the so-called "national key", so care was taken to ensure that "all our republics" have their representatives on that marble slab in Billiards.

A similar thing happened during the next decision on the winner.

Great Macedonian poet and significant social worker, codifier of the modern Macedonian language, academician Blaje Koneski he was the next winner (1975). For a good, "dark" book, but one that could hardly be said to represent the best of Koneski.

The next two awards made the principle of rewarding a specific work almost ridiculous.

In 1978, the great poet and revolutionary was awarded Oskar Davičo for the book of poetry "Words in Action". Only a few years later, Davičo did not even include his poetic dedication to self-improvement in the selected works.

That year, Davičo defeated the Slovenian partisan writer, an interesting storyteller, in the very final Mishka Kranjeca, but the main competitor was eliminated in the semi-finals. An exceptional book of poetry Radovan Zogović, the sumptuous and skillful "Princely Office" was not enough to overcome the political animosity that followed the great Montenegrin poet.

Although several of Zogović's friends and admirers sat on the jury, one of them, despite the firm promise given to the first winner, then member of the Jury, Mihail Lalić, that he would support the awarding of Zogović, was "broken" in the evening hours, in a long conversation with party arbitrators ... The normally restrained Lalić spat at him at the jury session.

Slovene party ideologue and critic of small scope, Josip Vidmar he was awarded in 1981.

His speech was just as cliche as his ideologically based observations about literature and culture - "Njegoš is Montenegro, Montenegro is Njegoš"...

The awarding of party critic Vidmar is, in a certain sense, a watershed in the annals of this award. The reaction of public opinion should not be underestimated either, which included the harshest criticism of such an award up to that time.

Vidmar was awarded for a thin book of essays called "Characters". The Slovenian title reads - "Cheeks". As soon as it was heard who the winner was, there was a joke that Vidmar was awarded - on the cheek...

Award to Desanka and not to Kiš

The next award will bring unprecedented polarization of the public, a media response that was unimaginable in the past. The procedures and work of the jury were "invisible" in all previous years. In the best communist manner, the public received only - final information.

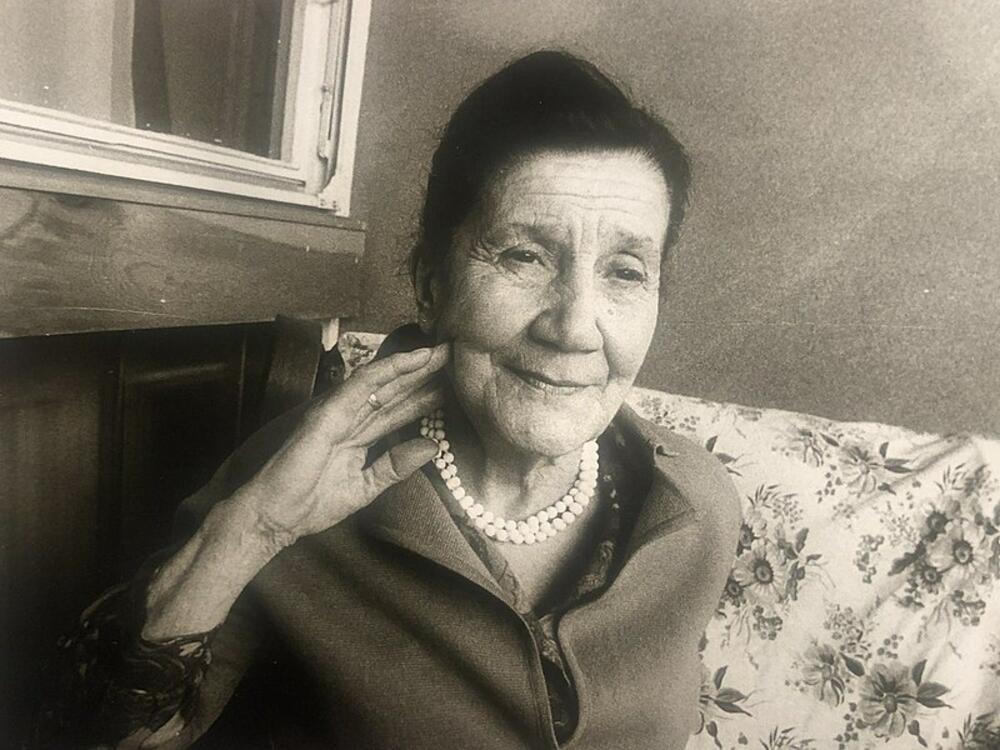

The general favorites entered the final selection Desanka Maksimović and, ever since the time of the famous polemic about the "Tomb for Boris Davidovič", the arch-enemy of the literary bazaar Danilo Kish.

Now, suddenly, at every step you could hear either the fans of Kiš (who was 49 years old at the time), or the eighty-six-year-old Desanka, a poet from numerous generations of readers in SRFJ.

Those who were in favor of Kiš, in addition to the most elementary literary reasons, believed that the awarding of the "Encyclopedia of the Dead" would bring a much-needed refreshment to an award, they believed that after all the party winners, the award is finally deserved by one - a pure writer. Also, Kiš rarely published, he belonged to the writers who write selected and not collected works, so there was a fear that the next book by Danilo would have to wait... In fact, it never came.

Desanka's fans repeated the hubris-mantra that "there is time for Kish, and Desanka is almost gone". You know how it ended - Kish died in 1989, at the age of fifty-four, and the poetess of "Bloody Fairy Tales" died at the age of 95, in 1993. Another lesson on why you shouldn't calculate when making decisions like this. By the way, until this year's award to the late Dubravka Ugrešić, Desanka was the only winner.

Let me have a personal tone as well. I remember the current TV columnist Vijesti, Ratke Jovanović, then a young journalist (or editor?) of Pobjeda culture, as Kiša passionately and lucidly advocated, as well as Miso Tripkovic, who debated equally skilfully (and noisily) on the topic of Kish or Desanka both in a bar and in the office of some politician... And I also remember how the high school graduate at the time, the current signatory of these lines, cheered fiercely. Almost with nostalgia, I recall that time and the way in which all these things were important to us.

After Kiš did not receive it, Njegoš's award still went to one of the writers from the circle to which Kiš also belonged. The time for rewarding party apparatchiks is over, at least that's how it seemed then. In 1987, he was the laureate of the Njegoš Award Borislav Pekić for the two final books of the monumental "Golden Fleece".

Admittedly, the one who thought that it was over with "political" awards would be mistaken. It was over with the old party, but a transition was coming and bringing its own miracles. It is an introduction to new (and different) politicization of the Njegoš award.

Yugoslavia was entering a turbulent period, and Montenegro was shaken by the AB revolution. Slobodan Milosevic decided to discipline Montenegro. His political action brought him to the historical stage Milo Đukanović i Momir Bulatović.

(End in the next issue of Art)

Bonus video: